The Marriage Book (73 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

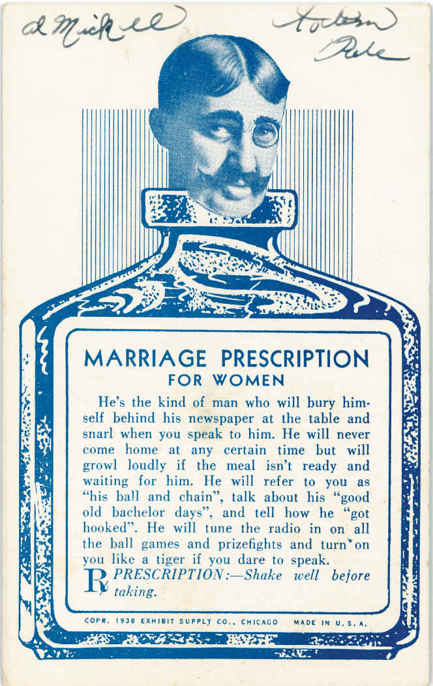

EXHIBIT CARD, 1938

Sometimes they were used to sell actual products, but in the 1930s and 1940s, “exhibit cards” were a thing in themselves, available in vending machines and offering everything from jokes to sports memorabilia to bathing beauties to the occasional message for women.

MARTHA GELLHORN

LETTER TO SANDY MATTHEWS, 1969

Journalist, novelist, and third wife of Ernest Hemingway, Martha Gellhorn (1908–1998) offered this bit of advice to the son she had adopted in 1949 from an Italian orphanage, adding a tentative corollary that men who were too close to their mothers might consequently “turn out to be fairies.”

Now I know enough to know that no woman should ever marry a man who hated his mother.

LIBERTY GODSHALL

“NO PROMISES,”

THIRTYSOMETHING

, 1989

Between 1987 and 1991, Baby Boomers tuned in weekly to watch as their television counterparts, a group of eight friends living in Philadelphia, passed through the milestones of early midlife in the hour-long ABC drama

thirtysomething

. The show touched many chords—and set off some controversy—with its exploration of changing sex roles, women’s careers, and marital fidelity.

Ellyn Warren is the childhood friend of main character Hope Steadman; Marjorie is Ellyn’s mother. This episode was written by actress/writer/producer Liberty Godshall, wife of series cocreator Edward Zwick.

MARJORIE: | You see, there are two kinds of boys in high school. There are the good-looking ones, the ones on every team, the ones everyone wants. They’re the greatest dancers too. And then there are the others—the boys who look as if they’d always rather be somewhere else reading a book, who are shy and awkward. I think you’d call them “nerds” now. Those are the boys to marry, Ellyn. Those are the boys who tell you secrets, who hold you when you cry in the middle of the night, who want to grow old with you. |

ELLYN: | How do you know about this, Mom? |

MARJORIE: | Because—I married a great dancer. |

WHY

BENJAMIN FRANKLIN

“THE OLD MISTRESSES’ APOLOGUE,” 1745

Apparently a friend had written to Franklin (see

Rings

;

When

) seeking a kind of blessing for premarital sex. In this letter, Franklin defended the institution of marriage.

Later in the letter, Franklin advised the friend that if he absolutely had to engage in “Commerce with the Sex,” he should choose an old rather than a young woman because, among other reasons, “in the dark all cats are gray.”

My dear Friend,

I know of no Medicine fit to diminish the violent natural Inclinations you mention; and if I did, I think I should not communicate it to you. Marriage is the proper Remedy. It is the most natural State of Man, and therefore the State in which you are most likely to find solid Happiness. Your Reasons against entring into it at present, appear to me not well-founded. The circumstantial Advantages you have in View by postponing it, are not only uncertain, but they are small in comparison with that of the Thing itself, the being

married and settled

. It is the Man and Woman united that make the compleat human Being. Separate, she wants his Force of Body and Strength of Reason; he, her Softness, Sensibility and acute Discernment. Together they are more likely to succeed in the World. A single Man has not nearly the Value he would have in that State of Union. He is an incomplete Animal. He resembles the odd Half of a Pair of Scissars.

CHARLES DARWIN

“THIS IS THE QUESTION,” 1838

Through his five-year, around-the-world voyage on the H.M.S.

Beagle

and his intense studies of flora, fauna, and fossils, Charles Darwin (1809–1882) developed the modern theory of natural selection. He had just returned from the trip, in fact, and was twenty-nine years old when he sat down to consider the arguments for and against marriage. That same year, he wrote to a friend: “As for a wife, that most interesting specimen in the whole series of vertebrate animals, Providence only knows whether I shall ever capture one or be able to feed her if caught.” The following year, Darwin married his cousin Emma Wedgwood. They went on to have ten children together.

This is the Question

MARRY Children—(if it Please God)—Constant companion, (& friend in old age) who will feel interested in one—object to be beloved & played with.——better than a dog anyhow.—Home, & someone to take care of house—Charms of music & female chit-chat.—These things good for one’s health. My God, it is intolerable to think of spending ones whole life, like a neuter bee, working, working, & nothing after all. No, no won’t do.—Imagine living all one’s day solitarily in smoky dirty London House.—Only picture to yourself a nice soft wife on a sofa with good fire, & books & music perhaps—Compare this vision with the dingy reality of Grt Marlboro’ St. Marry—Marry—Marry Q.E.D. | NOT MARRY No children, (no second life), no one to care for one in old age.— What is the use of working without sympathy from near & dear friends—who are near & dear friends to the old, except relatives Freedom to go where one liked—choice of Society & |

It being proved necessary to Marry—When? Soon or Late

The Governor says soon for otherwise bad if one has children—one’s character is more flexible—one’s feelings more lively & if one does not marry soon, one misses so much good pure happiness.— But then if I married tomorrow: there would be an infinity of trouble & expense in getting & furnishing a house,—fighting about no Society—morning calls—awkwardness—loss of time every day. (without one’s wife was an angel, & made one keep industrious).—Then

how should I manage all my business if I were obliged to go every day walking with my wife.—Eheu!! I never should know French,—or see the Continent—or go to America, or go up in a Balloon, or take solitary trip in Wales—poor slave.—you will be worse than a negro—And then horrid poverty, (without one’s wife was better than an angel & had money)—Never mind my boy—Cheer up—One cannot live this solitary life, with groggy old age, friendless & cold & childless staring one in one’s face, already beginning to wrinkle.—Never mind, trust to chance—keep a sharp look out—There is many a happy slave—

EMILY BRONTË

WUTHERING HEIGHTS

, 1847

Wuthering Heights

was the only novel written by Emily Brontë (1818–1848), who died of tuberculosis a year after its publication. Like her sister Charlotte’s

Jane Eyre

(see

here

and

here

) it is a classic tale of love and heartache on the Yorkshire moors. In this scene, the heroine, Catherine Earnshaw, describes her fateful decision to marry the wealthy, respectable Edgar Linton instead of her true love and former childhood companion, the orphaned and penniless Heathcliff. Nelly, the wise housekeeper and Catherine’s confidante, tells the story.

“Nelly, will you keep a secret for me?” she pursued, kneeling down by me, and lifting her winsome eyes to my face with that sort of look which turns off bad temper, even when one has all the right in the world to indulge it.

“Is it worth keeping?” I inquired, less sulkily.

“Yes, and it worries me, and I must let it out! I want to know what I should do. To-day, Edgar Linton has asked me to marry him, and I’ve given him an answer. Now, before I tell you whether it was a consent or denial, you tell me which it ought to have been.”

“Really, Miss Catherine, how can I know?” I replied. “To be sure, considering the exhibition you performed in his presence this afternoon, I might say it would be wise to refuse him: since he asked you after that, he must either be hopelessly stupid or a venturesome fool.”

“If you talk so, I won’t tell you any more,” she returned, peevishly, rising to her feet. “I accepted him, Nelly. Be quick, and say whether I was wrong!”

“You accepted him! then what good is it discussing the matter? You have pledged your word, and cannot retract.”

“But, say whether I should have done so—do!” she exclaimed in an irritated tone; chafing her hands together, and frowning.

“There are many things to be considered before that question can be answered properly,” I said, sententiously. “First and foremost, do you love Mr Edgar?”

“Who can help it? Of course I do,” she answered.

Then I put her through the following catechism: for a girl of twenty-two, it was not injudicious.

“Why do you love him, Miss Cathy?”

“Nonsense, I do—that’s sufficient.”

“By no means; you must say why?”

“Well, because he is handsome, and pleasant to be with.”

“Bad!” was my commentary.

“And because he is young and cheerful.”

“Bad, still.”

“And because he loves me.”

“Indifferent, coming there.”

“And he will be rich, and I shall like to be the greatest woman of the neighbourhood, and I shall be proud of having such a husband.”

“Worst of all. And now, say how you love him?”

“As everybody loves—You’re silly, Nelly.”

“Not at all—Answer.”

“I love the ground under his feet, and the air over his head, and everything he touches, and every word he says. I love all his looks, and all his actions, and him entirely and altogether. There now!”

“And why?”

“Nay; you are making a jest of it: it is exceedingly ill-natured! It’s no jest to me!” said the young lady scowling, and turning her face to the fire.

“I’m very far from jesting, Miss Catherine,” I replied. “You love Mr Edgar because he is handsome, and young, and cheerful, and rich, and loves you. The last, however, goes for nothing: you would love him without that, probably; and with it you wouldn’t, unless he possessed the four former attractions.”

“No, to be sure not: I should only pity him—hate him, perhaps, if he were ugly, and a clown.”

“But there are several other handsome, rich young men in the world: handsomer, possibly, and richer than he is. What should hinder you from loving them?”

“If there be any, they are out of my way: I’ve seen none like Edgar.”

“

You may see some; and he won’t always be handsome, and young, and may not always be rich.”

“He is now; and I have only to do with the present. I wish you would speak rationally.”

“Well, that settles it: if you have only to do with the present, marry Mr Linton.”

“I don’t want your permission for that—I

shall

marry him: and yet you have not told me whether I’m right.”

“Perfectly right; if people be right to marry only for the present. And now, let us hear what you are unhappy about. Your brother will be pleased; the old lady and gentleman will not object, I think; you will escape from a disorderly, comfortless home into a wealthy, respectable one; and you love Edgar, and Edgar loves you. All seems smooth and easy: where is the obstacle?”

“

Here!

and

here!

” replied Catherine, striking one hand on her forehead, and the other on her breast: “in whichever place the soul lives. In my soul and in my heart, I’m convinced I’m wrong!”

“That’s very strange! I cannot make it out.” . . .

. . . “I’ve no more business to marry Edgar Linton than I have to be in heaven; and if the wicked man in there had not brought Heathcliff so low, I shouldn’t have thought of it. It would degrade me to marry Heathcliff now; so he shall never know how I love him: and that, not because he’s handsome, Nelly, but because he’s more myself than I am. Whatever our souls are made of, his and mine are the same; and Linton’s is as different as a moonbeam from lightning, or frost from fire. . . .

. . . “Nelly, I see now, you think me a selfish wretch; but did it never strike you that if Heathcliff and I married, we should be beggars? whereas, if I marry Linton, I can aid Heathcliff to rise, and place him out of my brother’s power.”