The Marriage Book (77 page)

Authors: Lisa Grunwald,Stephen Adler

Tags: #Family & Relationships, #Marriage & Long Term Relationships, #General, #Literary Collections

WALTER: | Whaddaya want? |

HILDY: | Your ex-wife is here, do you want to see her? |

WALTER: | Well, hello, Hildy! |

HILDY: | Hello Walter. . . . |

WALTER: | Well, well. How long is it? |

HILDY: | How long is what? |

WALTER: | You know what. How long is it since we’ve seen each other? |

HILDY: | Oh well, let’s see, I spent six weeks in Reno, then Bermuda, oh about four months, I guess. Seems like yesterday to me. |

WALTER: | Maybe it was yesterday, Hildy. Been seeing me in your dreams? |

HILDY: | Oh no—Mama doesn’t dream about you anymore, Walter. You wouldn’t know the old girl now. |

WALTER: | Oh, yes I would. I’d know you any time— |

WALTER AND HILDY: | —Any place, anywhere— |

HILDY: | Aw, you’re repeating yourself, Walter! That’s the speech you made the night you proposed. |

WALTER: | Well, I notice you still remember it. |

HILDY: | Of course I remember it. If I didn’t remember it, I wouldn’t have divorced you. |

WALTER: | Yeah, I sort of wish you hadn’t done that, Hildy. |

HILDY: | Done what? |

WALTER: | Divorced me. Makes a fellow lose all faith in himself. Gives him a—almost gives him a feeling he wasn’t wanted. |

HILDY: | Oh, now, look, Junior, that’s what divorces are for. |

WALTER: | Nonsense. You’ve got an old-fashioned idea divorce is something that lasts forever—“till death do us part.” Why, a divorce doesn’t mean anything nowadays, Hildy. Just a few words mumbled over you by a judge. We’ve got something between us nothing can change. . . . |

HILDY: | . . . Look, now, Walter. What I came up here to tell you is that you must stop phoning me a dozen times a day—sending me twenty telegrams— |

WALTER: | I write a beautiful telegram, don’t I? Everybody says so. |

HILDY: | Are you gonna listen to what I have to say? |

WALTER: | Look, look, what’s the use of fighting, Hildy? I’ll tell you what you do. You come back to work on the paper—if we find we can’t get along in a friendly fashion, we’ll get married again. |

Y

YOUTH AND AGE

THALES OF MILETUS, CIRCA 6TH CENTURY BC

Thales of Miletus (circa 624 BC–circa 547 BC) was one of the earliest Greek philosophers and a pioneer in mathematics. His view below, about when to marry, was supposed to have been expressed to his mother, Cleobulina, when he was still in his early twenties. According to the historian Diogenes Laërtius, Thales nonetheless was said to have married, although when is not clear.

When a man is young, it is too early for him to marry; when he is old, it is too late; and between these two periods he ought not to be able to command leisure enough to choose a wife.

DECIMUS MAGNUS AUSONIUS

“TO HIS WIFE,” CIRCA 350

Ausonius was a Roman poet and teacher born in Bordeaux around 310. The best known of his works is a long poem called

Mosella

, which describes the countryside. But his

Epigrams

have also survived and are frequently translated. Epigram 20 is notable for its beauty; it is also, according to one scholar, unusual in that it applies the conventions of Latin erotic poetry to the state of marriage.

In Greek mythology, both the warrior Nestor and the prophetess Sibyl were famous for their advanced ages.

Love, let us live as we have lived, nor lose The little names that were the first night’s grace, And never come the day that sees us old, I still your lad, and you my little lass.

Let me be older than old Nestor’s years, And you the Sibyl, if we heed it not.

What should we know, we two, of ripe old age?

We’ll have its richness, and the years forgot.

ROBERT HERRICK

“TO THE VIRGINS, TO MAKE MUCH OF TIME,” 1648

English poet Robert Herrick (1591–1674), though a lifelong bachelor, wrote glowingly of sensuality, love, and—when it came to marriage—the virtues of seizing the day.

Gather ye rosebuds while ye may, Old time is still a-flying;

And this same flower that smiles to-day, To-morrow will be dying.

The glorious lamp of heaven, the sun, The higher he’s a-getting,

The sooner will his race be run, And nearer he’s to setting.

That age is best which is the first, When youth and blood are warmer; But being spent the worse and worst Times still succeed the former.

Then be not coy, but use your time, And while ye may, go marry;

For having lost but once your prime, You may for ever tarry.

ARNOT BAGOT

LEARN TO LYE WARM

, 1672

Like most proverbs, the one referred to in the title of this thirty-five-page pamphlet is undated, and the author is identified only as “a person of Honour.” We have been unable to locate any information about Arnot Bagot, except that he was a lawyer.

In Ovid’s

Metamorphosis

, Phaeton is reluctantly allowed by his father, the sun god Phoebus, to drive the chariot of the sun for a day. Phaeton is unable to control the horses, with the result that the earth is nearly frozen, then nearly burned up. To stop total disaster, Zeus kills Phaeton with a thunderbolt.

You say, that you cannot beleive that I, who have seen so many rare, excelent, and incomparable peices of nature; viewed them with so crittical an Eye; and set them forth with more than ordinary Commendations, should now fix my affection upon one, whose face in all probability must needs looke like the trees which mourne in October. . . . [I]n Common reason and prudence it is most proper, for a young man to marry a woman endowed with a larger flock of years than himself: . . . for youth to marry youth, what is it in nature but to add fuell to fire; to set a Giddy and Unexperienced

Phaeton

to guide the flaming Steeds of

Phoebus?

it is an old Proverb among horsmen, an old Horse to a young Man, and an old Man to a young Horse . . . that the staiedness and sobriety of the old Horse may prevent the precipitency and rashness of the young Man; and the discretion and moderation of the old Man, may correct the Fury and Wildness of the young Horse.

ROBERT BURNS

“JOHN ANDERSON MY JO,” 1798

Known as Scotland’s national poet, Robert Burns (1759–1796) started writing as a teenager, mostly love poems inspired by his many crushes. Son of a farmer, he was always poor, which did not stop him from writing, marrying, having affairs, and eventually fathering fourteen children, including nine by his wife, Jean Armour. In addition to succeeding with his many original poems, Burns was well known for publishing and/or rewriting traditional Scottish songs, including “Auld Lang Syne” and the once-bawdy “John Anderson, My Jo.” His two-stanza version is a beautiful ode to marriage in old age, ironic because the poet died at thirty-seven.

Burns wrote—and spoke—in the language known as Old Scots.

Jo

means “sweetheart”;

acqent

is “acquainted”;

brent

is “smooth”;

beld

is “bald”;

snaw

is “snow”;

pow

is “head”;

canty

is “merry”; and

maun

is “must.”

John Anderson my jo, John

When we were first acqent;

Your locks were like the raven, Your bonnie brow was brent;

But now your brow is beld, John, Your locks are like the snaw;

But blessings on your frosty pow, John Anderson my jo.

John Anderson my jo, John,

We clamb the hill thegither;

And mony a canty day John,

We’ve had wi’ ane anither:

Now we maun totter down, John,

But hand in hand we’ll go;

And sleep thegither at the foot, John Anderson my jo.

DUTCH PROVERB

Two cocks in one house, a cat and a mouse, an old man and young wife, are always in strife.

E.B.B.

“A LETTER TO YOUNG LADIES ON MARRIAGE,” 1837

Almost as popular a subject as whom and how to marry has been the question of the optimum age. For the almost certainly fictional “E.B.B.,” there was no mincing words for the recipient of this letter, his supposed ward.

Now

was clearly much better than

soon

or

later

.

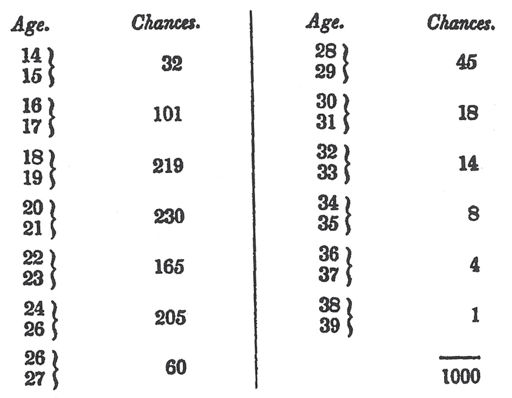

Of one thousand married women, taken without selection, it has been ascertained, by a long and tedious investigation, that the number of females married at each age is as follows: or if, by arithmetical license, we call a woman’s chance of marriage in her whole life 1000, her chances in each two years will be shown below:

Now, my dear Sarah, do lay this table to heart. It tells you that one

half

of a woman’s chances of marriage are gone when she has completed her

twentieth

year. And mind you what the consequence of this is,—she must then, as the sailors say, carry less sail and limit her views.

At twentythree years of age, she ought to be

very reasonable

; for

three-fourths

of the golden opportunities are gone, never to return. At

twentysix

, you will see at a glance that sauciness is out of the question, for your hopes, if the case should, unfortunately, be yours, will be reduced to the small fraction of

an eighth

. Possibly you may then think Rhyming Sandy a handsome fellow. At

thirtyone

, despair should begin to wrinkle your brow; for when that age comes and finds you single, pray remember that if you have in the whole circle of your acquaintances forty marrying men (a rare contingency), you have just one solitary chance amongst them all! When you stand on the dread verge of

thirtysix

, it is quite killing to reflect, that out of the thousand chances with which you started,

three

—a miserable remnant of

three

—only remains! . . . I am not of stern stuff, and can pursue the melancholy subject no farther, but again I entreat you, my dear Sarah, to lay the matter to heart.

Carpe diem

. . . or in plain English,

improve your time

.

STEPHEN CONRAD

THE SECOND MRS. JIM

, 1904

American author Stephen Conrad (1875–1918) created the engaging character of Mrs. Jim, the second wife of a well-to-do farmer and the devoted stepmother to his two sons. As chatty narrator, she dispenses wisdom on everything from courting to budgeting to baking—and, of course, marriage.

I tell you it pays to start right when you’re getting’ married. That’s one trouble with getting’ married young, ’specially for girls. They don’t know what they want, nor how to get it if they do know. But you take a middle-aged woman an’ let her get married, an’ she’s a might poor stick if she don’t know just what she wants, an’ get it. I’ll admit there’s one advantage in getting’ married young. If you’re goin’ to be happy, you’ll be happy lots longer, but then, there’s this disadvantage, if you ain’t goin’ to be happy, you’ve got that much more time to be miserable in. But when you get married at middle age, if you’re goin’ to be happy, you can be twice as happy, ’cause you know better how to be happy, an’ you know enough to have an easier time, an’ if you ain’t goin’ to be happy, you won’t be quite so miserable as if you didn’t know how to have an easy time, an’ you won’t be miserable so long.