The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) (3 page)

Read The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) Online

Authors: Jo Owen

•

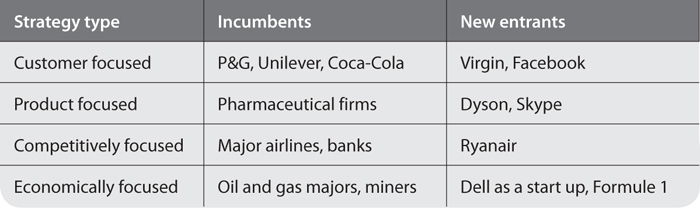

Competitively focused.

Can we stay level with or beat our peers? Incumbents tend to be in oligopolies where they follow each other with minor differences. New entrants come in with completely new approaches: think of the major airlines and the rapid arrival and growth of the low-cost carriers.

•

Economically focused.

Achieve economies of scale; lowest cost producer. Oil and gas firms are obvious examples. Many large car firms became obsessed with cost and economies of scale and forgot their customer focus and product quality, leaving the way open for new entrants from Japan.

To make it more complicated, there are differences between new entrants into the market and incumbents. Typically, incumbents layer one advantage on top of another. New entrants seek a big advantage in one area: they practice asymmetric warfare. Successful new entrants change the rules of the game in ways which the incumbents cannot follow. Here are some simple examples to make the point:

New entrants succeed not by copying the incumbents, but by being different. But their formula can be copied by other new entrants, so they quickly have to raise their game and start layering in new advantages. So Microsoft started out as product focused (by providing an operating system for early IBM PCs) and then became competitively focused, now dominating the market for desktop operating systems. Google followed suit. It started as product focused by providing a fast search facility, then built a unique economic model of paid search and finally is becoming competitively focused as it seeks to dominate the global market for organizing the world’s information. Google’s original product advantage was easy to copy; the economic model of paid search was harder to follow because Google had scale and reach others could not match. The final, competitive advantage of organizing the world’s information is so scale-sensitive it will be very hard for anyone to follow.

If you are an incumbent, strategy will be incremental and low risk: expand a product range or channel, reassess investment priorities. If you are a new entrant, do not play the incumbent’s game. Change the rules of the game so that the incumbents cannot follow you, and then change the rules of the game again so that other new entrants cannot follow you.

The goal of strategy is very simple: you have to find a source of unfair competition which results in making excess profits. Regulators and competitors should hate you for this, but without it, you fail. Every firm needs to make “excess” profits somewhere to stay alive: this profit sanctuary will help to pay for all the projects that go wrong, for investments that take time to mature, and to offset the impact of competition, customers, taxpayers, and staff who always seem to want more and give less.

You can only make excess profits if you have a source of unfair competition somewhere. All successful businesses have some form of unfair advantage, which other competitors find very hard to copy. For instance, you may:

• Have a license to drill oil in a low cost oil field (e.g. Exxon, Petrobas, Shell)

• Be in the best location on Main Street (e.g. McDonald’s, Starbucks)

• Own copyright or patents (e.g. Disney, Dyson, hi-tech firms)

• Be the first to move into a new market and dominate it (e.g. Google and paid search, Microsoft and desktop operating systems)

• Have a powerful brand (e.g. P&G, Unilever, Nike)

• Have a global network which is hard to copy (e.g. McKinsey and Goldman Sachs)

• Own a unique resource (e.g. Heathrow landing slots)

If you and your firm talk about “points of differentiation,” be very worried. That is a weak form of competitive advantage. Your goal is to have a thoroughly unfair advantage which allows you to make large amounts of money. The problem with a fair fight is that you might lose it: make sure the competitive fight is as unfair as possible.

What is your source of unfair competitive advantage?

Portfolio strategy is a classic MBA lesson. But as with some theories, the realities can be a stranger to the practice when it comes to corporate level strategy. The two main issues are that portfolio strategy is a flawed theory and practicing leaders think of their portfolio in a different way.

Your investment strategy is determined by the relative competitive position of your business and by the growth rate of its market. This gives rise to the following prescriptions:

• High relative competitive position, high growth market: reinvest cash to maintain share

• High relative competitive position, low growth market: milk the product for cash

• Low relative competitive position, high growth market: sell the business

• Low relative competitive position, low market growth: exit, close, sell

The theory breaks down as soon as it hits reality. The first big problem is about defining your market and your relative competitive position. For instance, Flash was a powdered floor cleaner with 45% share of a declining market (the powdered market). But if it was seen as part of all floor cleaners (including liquids and creams) it had about 20% of a growing market. Depending on the definition, you could say it was growing or declining and be perceived as a market leader or a me-too brand. How you define the brand defines your strategy.

The second problem with this approach is that if everyone follows it, you have collective marketplace insanity. For instance, milling and baking is a dull and declining business in many mature markets. So you would want to run it for cash or exit it. The more you run the business down, the more portfolio theory becomes a self-fulfilling prophecy. As no one invests in it, the industry disappears as surely as the Cheshire Cat leaving nothing but a smile behind. The same thinking would apply to steel and other mature industries.

If you are in an industry then that is your business and your future. It does not matter whether the theory says it should be growing or declining. As a leader, your job is to make the most of your business. So you should protect and grow it. If you are a steel maker, you could argue that making computer games is a more attractive industry with more growth and better margins. But that does not mean you should ditch steel and enter computer games. Your investors can make that decision in order to protect their investment portfolios, but you have your business to run. And even if the whole industry is in decline, there is still plenty of room for you to succeed:

• In the steel industry, Nucor grew by adopting a radically different model from the incumbents (recycling, mini mills versus large integrated mills).

• In milling and baking, RHM saw that other players were running their operations down. So they invested in their own milling and baking operations to make them the best and at lowest cost; they built share and protected margins.

Let shareholders worry about their portfolios; they can diversify at very low cost. As a leader, focus on your mission rather than worry about portfolio balance.

A vision is a story in three parts:

• This is where we are.

• This is where we are going.

• This is how we will get there.

And if you want to make the vision truly compelling, you add a fourth part: “and here is your very important role in helping us get there.” In other words, make the vision personal. Telling people that your vision is to increase earnings per share by 7% for the next five years is not wildly exciting: instead show how achieving this will help create growth and more job opportunities for all.

Often the best visions are the simplest: “We will become more customer focused,” “We are going to become international,” “We will professionalize our operations.” These are simple statements that everyone can understand, and they give you a script to follow for the rest of the year. If you are running a large organization, you may want a grander vision.

often the best visions are the simplest

If you want a big vision, try this one: “We will put a man on the moon within ten years.” Kennedy’s vision, in the wake of Sputnik, seemed like a pipe dream. But it was achieved. Since the vision, NASA has had successes and failures (Hubble and Challenger), but has lost its way compared to the time it was driven by Kennedy’s compelling vision.

To test your firm’s vision, think of Kennedy, NASA, the space race and Russia. RUSSIA is the acronym for what makes a good vision:

•

R

elevant: it meets a need which everyone inside the firm can recognize.

•

U

nique: you could not apply your vision to your competitors or to the local coffee shop.

•

S

tretching: “I will go to work most days” is not a great vision. “I will conquer the known world by the age of 30” is a bit more stretching: step forward Alexander the Great.

•

S

imple: if no one can remember it, no one can act on it.

•

I

mmediate: you have to act on the vision now and know when you have gotten there.

•

A

ctionable: each person in the firm must know what it means for them, and the firm must know how the vision will affect investment, decision making, measurements, and rewards.

How Russian is the vision for your firm and your team?

For the past 30 years at least, academic studies have shown that most acquisitions destroy value for the shareholders of the acquiring firm. The only winners are the shareholders of the acquired firm who typically enjoy a 40% bid premium on the shares they sell.

For CEOs, M&A activity is very attractive: it shows that you are doing something dramatic, it allows you to tell a story and it is quicker and easier than the grind of building the business organically. It also gives you a larger empire to run. For investment banks, M&A activity means fees for the acquirer and for the defense; fees for negotiating the funding; fees for then breaking up the merger and sorting out the financial mess five years later.

There are essentially three sorts of acquisition:

• The unrelated acquisition where the financial plays succeed in the medium term but few survive long term: the acquired company has little or nothing in common with the holding company. The acquirers used to be conglomerates like ITT or Hanson; nowadays they are likely to be private equity firms. In each case, the message is that the acquirer has found a superior way of managing any sort of firm. In practice, it relies on financial engineering (conglomerates) and large amounts of leverage (private equity). When times are good, profits rise and the acquirers look like geniuses. When recession hits and profits fall, they discover the dark side of leverage, which can be very dark indeed.

• The fill-in acquisition where the acquisitions become very expensive: this is designed to fill in a hole in a firm’s technology, capability, or market coverage. IBM has been buying dozens of mid-scale firms for precisely this reason: building a portfolio of competences fast. Arguably, it is cheaper to buy a market tested competence than try to build it internally. However, since every other major technology player has had the same idea, you will pay a high premium for your acquisitions.

• The scale acquisition, in industries where you face a simple choice: you can be predator or prey. “Economies of scale” are the holy grail of many acquisitions. The scale acquisition works in two ways. Internally, it enables the

firm to reduce unit costs: you reduce staffing levels, and reduce infrastructure spend on IT, facilities, factories, and the supply chain. Externally, it enables the firm to increase market dominance over both suppliers (by forcing them to reduce prices) and customers (removing market capacity and competition enables prices to rise). Inevitably, regulators become very interested when the scale acquisition leads to excess market dominance. Retailing banking for the past 30 years has been swamped by scale driven M&As, with huge savings to be made in people, property, and IT.

The fatal flaw with most acquisitions is that the acquirer pays too much for the acquisition. The logic of the deal may be right, but the price is often wrong. This happens because the thrill of the hunt overwhelms any logic. Investment bankers will be whispering in your ear, “Dare to be great.” The media will portray it as a hunt: you either get your kill or you have failed as a CEO.

The only known antidote to the madness of the hunt is a used envelope. On the back of it, work out the maximum you are prepared to pay for the target, with all the economies of scale. Do this before the hunt starts. Then keep the envelope in your pocket. If you are invited to pay too much, refer to your envelope and walk away. Ignore all the clever arguments of advisers who will always find ways of justifying an ever higher price: a used envelope has more integrity and impartiality than your highly paid advisers. And it costs less.