The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) (21 page)

Read The Mobile MBA: 112 Skills to Take You Further, Faster (Richard Stout's Library) Online

Authors: Jo Owen

a.

Financial costs: investment, advertising, infrastructure, sales costs, etc.

b.

Non-financial but quantifiable costs: time and effort involved, use of scarce resources such as R&D and IT.

c.

Non-financial and non-quantifiable costs: management distraction, opportunity cost versus not doing other projects.

But the biggest obstacles of all are the perceived risks of the project. The rational risks are relatively simple to deal with. The killers are the irrational risks: will this project make me look good or bad, will it lead to someone else grabbing the limelight, will it cut across another pet project? This is the political underbelly of any decision. For a decision to be successful, you have to align all the constituencies and all their interests before the decision is made.

4. Have I seen this pattern before?

Much of management is about recognizing patterns. If you have seen a movie a few times, you know what comes next. If, in management, you have seen the same situation several times, you know what to expect. You can then make the right decision. Old timers will call this “experience” or “business sense.” In practice, you do not have to wait 25 years to accumulate the wisdom of experience.

The simplest way is to have a good coach: a good coach is one who does not answer a question with a question. Your coach should be someone who has seen all the management movies many times and can tell you what is likely to happen next, depending on what you choose to do. You can accelerate your experience building by tapping into the knowledge of colleagues. Sales people love showing off their tricks of the trade to other people, and most managers are only too pleased to share their wisdom: it makes them feel valued and important. So use them.

5. How does this fit with the priorities, vision and values of the organization?

This is often a very simple way of deciding a close decision. If the firm is serious about customer satisfaction, then you deal generously with the customer’s request for a refund. If they pay lip service to customer service, you refer the customer to the customer support desk in Vladivostock. Work out the priorities of the organization: if a decision aligns with the needs of the CEO it is more likely to be approved than a decision which is not aligned.

I was once head of research for a political party, and it nearly cost me all my friendships. I always had data to back up my opinions and quickly discovered that people prefer opinions to facts. In the world of management, the battle of facts versus beliefs matters. If you understand how bosses and colleagues really make decisions, you are much better able to influence them. Fortunately, the work of Daniel Kahneman (Nobel Prize 2002) on decision-making heuristics shows what really goes on.

people prefer opinions to facts

Simplifying the theory, here is what managers need to know about how colleagues make decisions.

How colleagues make decisions

1. Anchoring.

Do more or less than 40% of the states in the UN come from Africa? The question is anchored around 40% and most people will guess close to that number. Moral for managers: strike early. Before the budget process starts, set expectations very low, before the planners put in some crazy planning assumption. Anchor the debate on your terms.

2. Loss aversion.

Losses are not just economic and rational. More importantly for managers, they are emotional: “will I look stupid if I agree to this?” Reversing a stated position loses face. So keep disagreements private while giving public fanfares even to partial agreements.

3. Social proof:

if Tim Tebow and Derek Jeter use the kit, maybe I can improve by using the same kit. Some hope. But endorsement works. So get the backing of some power brokers for your idea, and even the flimsiest case can succeed.

4. Framing.

Do you prefer savings and investment or cuts and spending? Easy choice, except that they are the same thing. Frame the discussion to suit your needs. Language counts, even if you are not an NLP fanatic.

5. Repetition.

All dictators and advertisers know this. Keep hammering the same message home. Repetition works. Repetition works. Repetition works. Repetition works... .

6. Emotional credibility.

If crime statistics get worse, so what? If my neighbor is robbed, crime is getting to be a serious problem. When I get mugged, then crime has spiraled out of control into a major epidemic. We believe what we hear and see, not what we read. Do not rely on PowerPoint. Make your point personally and personal: make it relevant to the person you want to influence.

7. Restricted choice.

Make it simple for your colleagues. If you offer them 10 alternatives, they will be paralyzed by indecision. Offer them a restricted choice of two, or at most three options: the very expensive option they cannot afford, the very cheap option which is no good, and the middle option which you want them to pick.

If you thought decision making was rational, think again. You have to work the political and emotional aspects of decision making as well. Understanding decision-making heuristics gives some clues as to how you can influence decisions in your favor.

Crises are not just inevitable: they are good. They are a great way of separating out the leaders from the losers. Fortunately, organizational life is the perfect breeding ground for crises, so you should get plenty of opportunity to display your talents in managing crises. If you cannot manage a crisis, you cannot manage the organization, so it is a skill worth building. It is also where you will achieve far more visibility than in your routine day job, and it will give you a claim to fame when promotion comes around. So do not run away from crises: embrace them and make the most of them.

Every crisis unfolds in its own messy way. But here are four basic principles for turning disaster into triumph:

•

Do not go into denial.

Crises do not solve themselves. If anything, they tend to get worse quickly. So recognize the problem and be ready to deal with it if it is your crisis. If it is someone else’s then stand aside, but be ready to respond positively when asked. Do not offer gratuitous help or advice, it will nearly always be misinterpreted for the worse.

•

Move to act fast.

Colleagues may go into avoidance or analysis mode because that is safe, even if it achieves nothing. This gives you the chance to take control, lead, and to make your mark. Even if your first steps are in the

wrong direction, do not worry: most people will be delighted that someone is taking the problem away. You can always alter course as you go along.

•

Over-communicate and build your crisis coalition.

As you lead, others will follow. But part of leading is having a clear and simple story which everyone understands about what you are doing. If you do not provide the storyline, then others will create a story about the crisis anyway: their story will invariably be negative. So keep control of the narrative and make sure all the power brokers support what you are doing and your story. This takes an endless amount of time: crises are time hungry events.

•

Be positive.

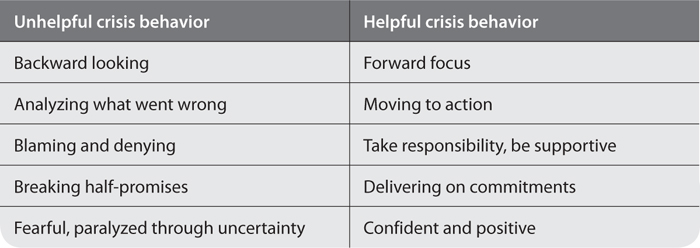

Crises are marked by people running round in circles and blaming each other. You will be remembered not just for what you did, but for how you did it. So focus on the right behaviors:

Crises accelerate your career: you succeed fast or fail fast. Learn to manage them well.

Pierre-Francois was

chef du cabinet

of a leading French government ministry. He loved meetings: “They are a great opportunity to sabotage other ministers’ plans,” he declared, gleefully.

The purpose of meetings is unclear to many managers. Some meetings are held because they are always held. Others meetings are a convenient way of appearing busy while sharing and avoiding personal responsibility for anything. And far too many meetings go on far too long. The Queen has an effective way of keeping meetings short. When the Privy Council of senior ministers meet her, the meeting is a standing meeting. Even windbag politicians get to the point faster when they are forced to stand.

The basic test for any meeting is simple: “What will be different as a result of this meeting?” If nothing will be different, spend the time more productively

and have a gossip by the coffee machine. The difference test can be refined into three more questions:

• “What did I learn from the meeting?”

• “What did I contribute or achieve in the meeting?”

• “What will I and others do differently as a result of the meeting?”

A good meeting will have good answers to all three questions for all attendees. If you are invited to a meeting where you expect to draw a blank on all three questions, do not go. If you are inviting people to attend one of your meetings, only invite those who will be able to answer all three questions positively by the end of the meeting. Construct the agenda so that you can achieve this result.

A classic error is to go to a meeting to “get exposure” to senior management. If you do that and have nothing to contribute, then you will have achieved the goal of getting exposure: all the senior managers will now assume you are someone with nothing useful to say or contribute. That is not the best way to establish a reputation. Of course, it may be that the formal agenda offers nothing for you, but the most critical part of the meeting may be the five minutes before and after the formal meeting. This may be your chance to quickly meet someone who has been very hard to reach and to set up a full, follow-up meeting with them.

Life is short and meetings can be long. Do not waste life.

When do you push and when do you hold back? How hard do you push? These are mysteries which you’ll only learn from experience. But experience is no more than pattern recognition: once you have seen the same sort of movie 10 times, you know what is likely to happen next. So here is what happens in different sorts of meeting movie, and what you can do about it.

• Is the decision important to me? If not, relax. Never pick a pointless battle, and that includes making gratuitous contributions to the debate which may keep one side happy and irritate the other.

• Is the outcome clear? If it is, stay relaxed. Let the debate come to its inevitable conclusion.

• If the outcome is unclear, it is an important decision and you are not in the power seat, do not relax. Be prepared to strike early and to anchor the debate on your terms. Your only hesitation should be to check that none of the big

power brokers have a strong view which you were unaware of, or they may simply have information you did not know about. Otherwise, be bold and set the debate. To hedge your position you can frame the debate around three options: two should be easy to knock down and the middle one is the one you want everyone to pick anyway. When faced with objections do not fight them, agree with them (“Yes, that is something which troubled us greatly when we developed the idea, and this is how we dealt with it...”).

• If you are in the power seat, you can orchestrate the conversation to get your desired outcome while appearing neutral. Ensure the first person to speak will anchor the debate where you want it to be anchored. Then let the debate roll: everyone will want to be heard. For the most part, everyone is likely to cancel each other out. Once everyone has fought themselves to a standstill, summarize carefully: thank each person for one specific (and of course, brilliant and insightful) comment that they made. They are now 100% committed to agreeing with your summary because it supports them (at least on one point). And your summary will lead you to exactly where you wanted to be at the start of the discussion. End of discussion, game over.

meetings should never be used to make decisions

Finally, remember that meetings should never be used to make decisions: there is a risk that attendees may make the wrong decision. Meetings should be used to confirm in public the agreements you have reached in private. So by the time you get to the meeting, you should know you have enough support, and you should also know who will object and why they will object. There should be no surprises.

Corporate conferences cost a fortune and often achieve little. Here is how to make the most of them.

Most corporate conferences have three sorts of session: plenary sessions, break outs and informal sessions. Treat each differently.

•

Plenary sessions

are there to allow the great panjandrum to pontificate. They impress no one except themselves. You will not be missed, so you can drop this session while you do something worthwhile. You can normally pick up a copy of the slides, and colleagues will tell you what it was like. If you see the main speaker, say how greatly impressed you were by the speech.