The Monks of War (34 page)

In April 1451 the Bastard of Orleans also invaded Guyenne, bringing with him Maître Bureau and an even more imposing artillery-train. He advanced on Bordeaux. He quickly took Blaye, Fronsac and Saint-Emilion, isolating the ducal capital, which he invested. Despite a brave defence by the Captal de Buch, Gaston de Foix KG, Bordeaux surrendered on 30 June. By the end of July only Bayonne held out for the Plantagenets, and that too fell on 20 August. Bribery contributed a good deal to the speed of the French conquest ; Bergerac is said to have been betrayed by its Captain, Maurigon de Bideron—who also sold the castle of Biron—and the English Mayor of Bordeaux, Gadifer Shorthose, received a pension for his disloyal services.

However, although some Gascon nobles at first welcomed the French, the Guyennois quickly began to hate their new masters. The northern French administrators and tax men proved harsh and efficient, contemptuous of the old ways, while Charles’s troops behaved as unpleasantly as the English soldiers had in Normandy. In 1452 secret envoys reached London and promised the Duke of Somerset that Bordeaux would rise for him if he sent an army.

Somerset was overjoyed. The Commons had already accused him of causing the loss of Normandy, and when Guyenne had gone too there was uproar; the Duke of York had marched on London with an army and Somerset only retained power by the skin of his teeth. The recovery of Guyenne could well win him some desperately needed popularity.

The English still believed that one Englishman was worth two Frenchmen, and their hero Talbot shared this view. As has been seen, he was made a hostage in 1449 and was thus the one English commander in Normandy whose reputation had remained intact. Although an old man in his seventies by now—the French thought he was in his eighties—he was as vigorous as ever, retaining all his pugnacity and magnetism. The natural choice to lead the expedition, he was appointed the King’s Lieutenant in Guyenne in September 1452. Yet the great Lord Talbot was now to meet his match.

If the French had no paladin of equal distinction, they did possess a technocrat—Maître Jean Bureau. Bishop Basin, who almost certainly met the great gunner, describes him as ‘a man of humble origins and small stature, but of purpose and daring’. Bureau was a native of Champagne who came to Paris to become a lawyer and who is known to have been a legal official at the Chatelet in the days of the Duke of Bedford. In 1434 he left what was still the Anglo-French capital to enter the service of Charles VII, who appointed him Receiver of Paris two years later and promoted him to be Treasurer of France in 1443. It may seem odd that a lawyer and civil servant should also be a professional artillery expert, but during the fifteenth century master gunners were usually civilian specialists under contract who, like Bureau, founded their own cannon. According to Basin, Bureau had first served as a gunner with the English, and no doubt he and his brother Gaspard (who worked with him) were originally attracted to the profession largely by commercial considerations. However, they served Charles VII with outstanding success. Long before the Norman campaign, the Bureau brothers’ guns had proved their worth—at Montereau in 1437, at Meaux in 1439, at Saint-Germain-en-Laye in 1440 and at Pontoise in 1441. In Jean Bureau one discerns a perfectionist with a methodical, mathematical mind, a brilliant administrator and an imaginative technician who knew how to get the best out of his primitive weapons.

During the fifteenth century the tools of the Bureau brothers’ difficult and dangerous trade had slowly improved. The most important innovation was the powder mill, invented about 1429. Before then gunpowder had had to be mixed on the field, but now the new ‘corned’ powder-grains no longer disintegrated into their three separate components of sulphur, saltpetre and charcoal. The new powder increased velocity enormously. There had also been advances in casting cannon, in bronze, brass and, more rarely iron, even if the weapons were still apt to burst. (During the siege of Cherbourg it was a matter for congratulation that only four blew up.)

Moreover a cheap and reasonably effective manual firearm had been developed. These

batons-à-feu

or handguns were confusingly called culverins like the cannon of that name. They had barrels of brass or bronze, and straight wooden stocks and—mounted on a rest—were aimed from the chest instead of from the shoulder. They fired a lead bullet, using a special explosive powder twice as expensive as that for bigger guns. The firing mechanism was a ‘serpentine’, an S-shaped attachment of which one end acted as a trigger and the other held the match. (A serpentine was also a type of small cannon.) Although half the price of steel crossbows, such guns were not often used in the field as they were too cumbersome. However, mounted on a rampart they could be effective enough in siege warfare.

On 17 October 1452 Talbot landed in the Médoc with 3,000 troops. The French knew about the expedition but expected it to land in Normandy, so in consequence they had no proper army in Guyenne. As promised, the Bordelais rose against the Seneschal, Oliver de Coetivy, turned out the French garrison and opened the gates. The English marched in on 21 October. All western Guyenne now rose and the few towns and castles garrisoned by the French were speedily overrun. Charles VII, taken completely by surprise, left Talbot in peace but spent the winter organizing a counter-attack for the following year. Before the end of the winter 3,000 more men reached Talbot, under his fourth and favourite son, Viscount Lisle.

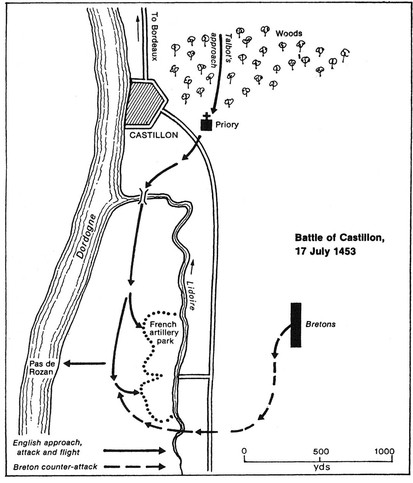

By the spring of 1453 King Charles was ready. Three French armies invaded Guyenne, from the north-east, the east, and the south-east, all making for Bordeaux. Talbot’s strategy was to wait and try to engage each one separately. In July the French army which was advancing from the east laid siege to the town of Castillon near Libourne on the Dordogne, about thirty miles up-river from Bordeaux. Talbot was inclined to leave the townsmen of Castillon to their fate, but they pleaded with him so eloquently that he reluctantly agreed to come and save them.

The enemy army in question consisted of about 9,000 troops. It had no designated commander and its senior officers were far from united. However in matters of gunnery they wisely deferred to Jean Bureau, who obviously had some sort of ascendancy over them. As was customary in siege warfare, he had built a fortified artillery park just out of range of Castillon’s guns, his actual batteries being probably much nearer and connected to the park by communication trenches. This was not a revolutionary exercise in military engineering as has been suggested, but a routine precaution against sorties by the townsmen or relief forces. The actual park, which was constructed by 700 pioneers, consisted of a deep trench with a wall of earth behind it which was strengthened by tree-trunks ; its most remarkable feature was the irregular, wavy line of the ditch and earthwork, which enabled the guns to enfilade any attackers. Bureau knew all about cross-fire. The park was about half a mile long and about 200 yards wide, lying parallel to the river Dordogne which was less than a mile away, while one side was completely protected by the Lidoire, a tributary of the Dordogne.

Bureau had brought 300 cannon with him, mainly culverins. It seems extremely likely that these were handguns. (Perhaps chroniclers were confused by ‘culverins with serpentines’ and heard ‘culverins

and

serpentines’ instead.) If so, the English military supremacy which had begun with bows was about to be ended by small arms. The guns were mounted on the earth wall.

On 16 July Talbot rode out from Bordeaux with his entire army, which included a Guyennois contingent and may have been as many as 10,000 men. He covered 20 miles, reaching Libourne by sunset though outdistancing his infantry and retaining only 500 men-at-arms and 800 mounted archers. At daybreak the following day he and his little force suddenly emerged from the woods near Castillon and annihilated a French detachment in a nearby priory. He then learnt of the artillery park and, after sending Sir Thomas Evringham to examine it and refreshing his men with a cask of wine, settled down to wait for the rest of his troops to catch up with him. But a messenger came from Castillon to say that the French were running; in fact the townsmen had seen a cloud of dust raised by the horses of enemy supernumeraries who had been sent away. Thinking the entire enemy army was in full retreat, Talbot at once led his men in an attack on the park. The only man to remain mounted, the veteran warrior, seventy-five years of age, must have been a striking figure in a gown of crimson satin, with a purple bonnet over his snowy hair. He had been forced to swear not to wear ‘harness’ (armour) against the French when they released him from his captivity in Normandy.

The English and Gascons charged the French camp, shouting ‘Talbot! St George!’ Some managed to cross the ditch and a few scaled the earthworks, including the standard-bearer Sir Thomas Evringham who was at once shot dead. The enemy guns fired into the English at point-blank range—because of the enfilade one shot killed no less than six men. Despite impossible odds the assault lasted for nearly an hour, small detachments of Talbot’s other troops coming up to join in the fight. Then a thousand Bretons appeared unexpectedly on the far side of the Lidoire, attacking the English from the south and crashing into their right flank. According to Monstrelet’s continuator, the Bretons ‘fell upon them and trampled all their banners underfoot’. But the issue was never in doubt—even without the Bretons, Bureau’s guns would have broken the English. They began to run towards the Dordogne behind them, while Talbot and his son tried desperately to rally some men to cover their retreat over a ford, the Pas de Rozan. But the old hero was a good target and his horse was brought down by a gunshot, pinning him underneath ; a French archer called Michel Perunin finished him off with an axe. A few English got away though most were killed, including Lord Lisle; the pursuit continuing as far as Saint-Emilion. The English army had been completely destroyed.

By the end of September Bordeaux alone held out against the French. The city was closely besieged and the Gironde blockaded. The Bordelais could hope for no relief from Somerset’s feeble government; even the English survivors from Castillon thought only of going home. On 19 October 1453 the capital of Guyenne surrendered unconditionally, trusting—somewhat optimistically—to the mercy of King Charles. One of his first acts was to make Maître Jean Bureau Mayor of Bordeaux for life. But nobody seems to have realized that the Hundred Years War was over.

12

Epilogue

An if I live until I be a man,

I’ll win our ancient right in France again,

Or die a soldier, as I liv’d a king.

King Richard III

to the intent that the honourable and noble adventures of feats of arms, done and achieved by the wars of France and England, should notably be enregistered and put in perpetual memory.

Lord Berners’s translation of Froissart

In the end the Hundred Years War bankrupted the English government and fatally discredited the Lancastrian dynasty, though England herself may well have been richer from a century of ‘spoils won in France’. In August 1453 Henry VI went mad and six months later the Duke of York became Protector. When Henry recovered in 1455 and re-instated the Beauforts, that long and murderous conflict known as the Wars of the Roses broke out, veterans using the combat skills they had learnt in France on each other. English noblemen had become accustomed to fighting as a way of life and the men-at-arms and archers in their retinues desperately needed employment. York and Somerset fell in battle, Kyriell and Rivers died on the scaffold, Scales was lynched by a Yorkist mob, and many of the men who were killed at St Albans and Towton or even at Barnet and Tewkesbury had fought under Old Talbot. The rise of the House of York and the Wars of the Roses cannot be understood without some knowledge of the Hundred Years War.

At first the English regarded their expulsion from Normandy and Guyenne as purely temporary. At Bordeaux and Bayonne the French had to build citadels to cow the Guyennois, and in 1457 Charles VII wrote apprehensively to the King of Scots how he ‘had to watch the coast daily’. In 1475 Edward IV (son of a Lieutenant General of France, and born at Rouen) at last marched out from Calais towards the Somme ; however, at Picquigny he signed a seven-year truce with Louis XI, agreeing to withdraw for an indemnity of 75,000 crowns and an annual pension of 60,000. But no proper peace treaty was ever signed, and as late as 1487 Henry VII hoped to recover Guyenne ; he intervened in Brittany the following year and invaded France in 1492. Henry VIII also took an army across the Channel, defeating the French at the Battle of the Spurs in 1513 and capturing Thérouanne and Tournai—the first French towns gained by English arms since the days of Bedford and Old Talbot. In 1523 he signed a secret treaty with the Duke of Bourbon and the Emperor Charles V, which would have given him the French crown together with Paris and the north-western provinces of France and would have restored the Lancastrian dual monarchy. This came to nothing, though in 1544 he took Boulogne. Even after the loss in 1558 of Calais, their last foothold, English monarchs continued to call themselves Kings or Queens of France until the Treaty of Amiens in 1802.