The Monks of War (8 page)

The noble King Edward III. 1312-1 1377) whose face was said to be like the face of a god’.

The Count of Alençon was so shocked by what he considered to be cowardice on the part of the crossbowmen that he shouted, ‘Ride down this rabble who block our advance!’ His fellow men-at-arms immediately responded to his appeal with a hopelessly disorganized charge. The shrieks of the miserable crossbowmen trampled under horses’ hooves made the French in the rear think that the English were being killed, so they too pressed forward. The result was a struggling mob at the very foot of the slope where the English archers were positioned and from where they shot with murderous precision, not wasting a single arrow; each one found its mark, piercing the riders’ heads and limbs through their mail and above all driving their mounts mad. Some horses bolted in a frenzy, others reared hideously or turned their hindquarters to the enemy. ‘A great outcry rose to the stars.’ Jean le Bel, who had spoken to men who were there, tells of horses being piled on top of one another ‘like a litter of piglets’.

Almost certainly Edward’s guns added to the confusion. At least one chronicler says that the King’s cannon—only three are mentioned—terrified the horses. If of little use as weapons, their noise and smoke must have appalled those who had never experienced them.

Surprisingly, some French knights reached the forward English divisions, where the men-at-arms hacked them down with axes and swords. Either in this charge or during a later one the sixteen-year-old Prince of Wales was knocked off his feet, whereupon Richard de Beaumont, the standard-bearer, in a magnificent gesture covered the boy with the banner of Wales and fought off his assailants till the Prince could stand up. Froissart has a romantic tale of how when the Prince’s companions sent to Edward for help, the King refused, saying, ‘Let the boy win his spurs for I want him, please God to have all the glory.’ However another chronicler (Geoffrey le Baker) says that the King did in fact send twenty picked knights to relieve his son. They found the boy and his mentors leaning on their swords and halberds, recovering their breath and waiting silently in front of long mounds of corpses for the enemy to return.

An enemy who reached the English lines was the blind King John of Bohemia. He ordered his attendant knights to lead him forward ‘so that I may strike one stroke with my sword’. Somehow the little party, tied to each other by their reins, managed to ride through the archers and then charge the English men-at-arms. There the Bohemians fell with their King, save for two who cut their way back to the French lines to tell his story. The bodies were found next day, still tied together. The Prince of Wales was so moved that he adopted the old King’s crest and motto—the three feathers with the legend

Ich dien

—I serve.

The French charged fifteen times, ‘from sunset to the third quarter of the night’, each charge beginning as well as ending in hopeless disorder beneath the arrow-storm. Froissart says that no one who was not present could imagine, let alone describe, the confusion, especially the disorganization and indiscipline of the French. The slaughter was heightened by the Welsh and Cornish knifemen who ‘slew and murdered many as they lay on the ground, both earls, barons, knights and squires’. The last French attacks were launched in pitch darkness. By then there were few French knights left—apart from those who were dead, many had been quietly slipping away since the onset of dusk. King Philip, who had been hit in the neck by an arrow and had had at least one horse killed under him, found that he could only muster sixty men-at-arms when he tried to mount a final desperate charge through the gloom. The Count of Hainault took hold of the King’s bridle and persuaded him to leave the field—‘Sir, depart hence, for it is time. Lose not yourself wilfully; if ye have loss at this time, ye shall recover it again at another time.’ They rode to the royal château of La Broye six miles away. When he arrived there, with only five companions, Philip shouted to the castellan, ‘Open your gate quickly, for this is the fortune of France.’ The King only stopped to drink and then rode on through the night to find a safer refuge at Amiens.

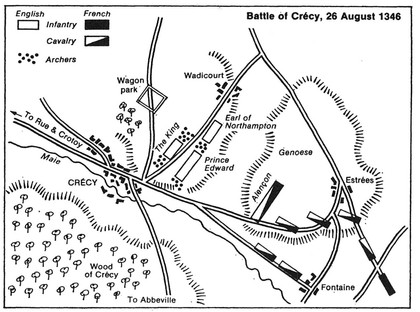

The English who, because of the dark, did not realize the fearful casualties which they had inflicted, slept at their positions, so relieved at having escaped annihilation that they prayed to God in thanksgiving. They had lost less than a hundred men themselves. Next morning they awoke in such thick fog ‘that a man might not see the breadth of an acre of land from him’. Edward forbade any pursuit. He sent out a scouting force, 500 men-at-arms and 2,000 archers under the Earl of Northampton, who soon found themselves facing some local militia and then a force of Norman knights who had arrived too late. Northampton’s men quickly routed these last opponents, killing many. The King now saw the extent of his victory and ordered heralds to count the slain. They identified the bodies of more than 1,500 lords and knights, among them the Duke of Lorraine and the Counts of Alençon, Auxerre, Blamont, Blois, Flanders, Forez, Grandpré, Harcourt, Saint-Pol, Salm and Sancerre. Froissart exaggerates the number of ‘common people’ on the French side who died, but it was certainly well over 10,000.

Edward had won one of the great victories of Western history. Until Crécy the English were very little thought of as soldiers, while the French were considered the best in Europe. Tactically and technologically the battle amounted to a military revolution, a triumph of fire-power over armour. The King of England became the most celebrated commander in Christendom.

However, Edward was in no position to exploit his victory. Although Philip’s army had been destroyed, he dared not march on Paris with his tired troops. On 30 August he set off for the coast to capture a port. He chose Calais, which he reached on 4 September. It was only a few miles from the Flemish border and was the nearest port to England. Soon English ships arrived with reinforcements and took home the wounded as well as prisoners and plunder. The King had expected to take the town without much trouble but found that it was stronger than he had thought—surrounded by sand dunes and marshes on which it was impossible to erect siege engines. Deep dykes made mining out of the question. Moreover it had a strong garrison commanded by a gallant Burgundian knight, Jean de Vienne, who was determined to hold out until winter came and the English would be forced to withdraw. But Edward was equally determined, and built wooden huts to house his troops during the winter. Jean le Bel says that he ‘set the houses like streets and covered them with reed and broom, so that it was like a little town’; it even had market days which did a thriving trade. Many Englishmen died from disease, but the rest kept on grimly with the siege throughout the winter, devastating the country for thirty miles around. In the spring Edward brought over more reinforcements, in case Philip should try to relieve the town. Parliament was co-operative, supplying the necessary funds, and by mid-summer 1347 the English had over 30,000 men outside Calais. All this represents a remarkable administrative achievement—not only the new troops but also vast quantities of food to feed them had to be ferried across the Channel.

King Edward’s real weapon was a ruthless blockade by his ships, calculating that ‘hunger, which enters closed doors, could and should conquer the pride of the besieged’ according to the Oxfordshire chronicler Geoffrey le Baker. Palisades running out into the sea prevented small boats from bringing supplies along the shore to the beleaguered garrison. A large English fleet was always waiting outside the harbour, and they built a wooden tower with catapults to destroy any vessel which might possibly slip through. The citizens expelled 500 of their poor to save food, but by the spring supplies were running out; they decided that they would have no option other than to surrender if Philip did not relieve them by August.

One reason why Edward was able to find so many troops was the recent elimination of any danger from Scotland :

For once the eagle England being in prey

To her unguarded nest the weasel Scot

Comes sneaking, and so sucks her princely eggs.

In October 1346 David II had invaded Northumberland and Co. Durham, to meet with the fate of all Scottish invaders at Neville’s Cross near Durham. The Scots were annihilated, their King being taken prisoner to the Tower of London where he spent nine years. His nation’s most sacred relic, the Black Rood of Scotland, was triumphantly hung up in Durham Cathedral.

In July 1347 Philip at last marched to relieve Calais. His army was neither so large as that of the previous year nor so eager for battle. Looking down on Edward’s camp from the cliffs at Sangatte only a mile away, he set up his own camp and then sent a challenge to the English King to come out and fight, but Edward refused to leave his snugly fortified siege lines. Philip knew that to attack would be to invite another Crécy and tried unsuccessfully to negotiate a truce. On 2 August he ordered his men to strike camp and set fire to their tents. The retreating French army could hear the lamentations of the doomed people of Calais as they rode away—its garrison threw the royal standard down into the ditch.

By now even the richest of those inside Calais were dying from lack of food and the day after Philip’s withdrawal Jean de Vienne appeared on the battlements to shout that his garrison was ready to negotiate. He was told how the English King was so furious at the town’s resistance that its people would have to submit to being killed or ransomed as he chose. Eventually Edward was persuaded to limit his punishment to the six chief burgesses, who had to appear before him clad only in their shirts and with halters round their necks. ‘The King looked felly on them, for greatly he hated the people of Calais.’ Then he commanded their heads to be struck off. They were only saved by the intercession of the pregnant Queen Philippa who knelt before her husband in tears and pleaded, ‘Ah, gentle sir, since I passed the sea in great peril, I have desired nothing of you; therefore now I humbly require you in honour of the Son of the Virgin Mary and for the love of me that ye will take mercy of these six burgesses.’ Nonetheless Edward turned all the inhabitants out of the town in the clothes they had on and nothing else, later re-peopling it with English colonists who were assigned shops, inns and tenements. He gave many of the fine houses of the rich bourgeois to his friends.

For two centuries Calais was to be the English gate into France—both entrepôt and bridgehead. A commentator has written, ‘The vital importance of Calais to the English is perhaps best realized if one were to imagine France in possession of Dover throughout the war, and the advantage this would have given her.’ The English soon felt passionately about Calais ; as Philip Contamine, the modern French historian, says, ‘For two centuries it remained a little piece of England on the continent,’ and it was even part of the diocese of Canterbury.

Yet the town’s acquisition should not be seen in isolation, as the Crécy-Calais campaign was only one of the three interdependent operations of Edward III’s grand strategy. In the south-west the Earl of Derby was able to hold on to most of his gains ; he had been besieged at Aiguillon, but the Duke of Normandy raised the siege as soon as he heard of his father’s defeat and took his army north of the Loire. One of the reasons which may have made Philip abandon Calais was news of another English victory, in Brittany at La Roche Derrien where an English garrison was besieged. On 27 June 1347 Sir Thomas Dagworth wiped out the forces of Charles of Blois, who was captured and sent to join the King of Scots in the Tower of London. Only in Flanders did the English position grow weaker, the new Count (the strongly pro-French Louis de Male) managing to win over the towns.

The Papacy deplored the misery caused by Edward’s campaigns. In 1347 Clement VI remonstrated with the King, writing to him of ‘the sadness of the poor, the children, the orphans, the widows, the wretched people who are plundered and enduring hunger, the destruction of churches and monasteries, the sacrilege in the theft of vessels and ornaments of Divine worship, the imprisonment and robbery of nuns’.

At the Pope’s intervention England and France agreed to a truce, in September 1347. King Philip was in a desperate position. Not only had his armies been routed but he was without money. Yet he had to rebuild his strength without delay in case of another invasion. This proud and haughty man abased himself before the Estates when they met in Paris in November. Their spokesman told him, ‘You, by bad counsel, have lost everything and gained nothing,’ adding that the King had been ‘sent back scurvily’ from Crécy and Calais. They would not grant him any money. With great difficulty Philip’s officials managed to extract a little from the local assemblies and the clergy. Even now, after so many years of frustration and humiliation, he still planned to invade England.

Edward III basked in the adulation of his subjects. The Parliament Roll records how both Lords and Commons approved motions thanking God for their King’s victories and agreeing that the monies which they had voted him had been well spent. The ‘realm of England hath been nobly amended, honoured and enriched to a degree never seen in the time of any other King’.