The Monks of War (9 page)

It was probably in June 1348 that Edward formally founded the Order of the Garter at Windsor, based on an association of knights on the model of the Round Table some years before. It seems that the legend is true, that the first Garter was dropped by the beautiful Countess of Salisbury while dancing and that the King—who was in love with her—fastened it round his own knee, saying

‘Honi soit qui mal y pense’

to save her from embarrassment. (The blue, different from today’s Garter blue, was no doubt derived from the royal blue of the French arms.) Membership of the Order was to be the crown of a successful military career throughout the Hundred Years War ; it is noticeable how many leading commanders received the Garter right up to the very end of the War, both English and Guyennois—with some exaggeration it may be compared to the Companionship of the Bath (CB) during the Peninsular War.

The incident of the Countess of Salisbury and her garter is said to have taken place at a triumphant banquet at Calais, in celebration of its capture. The King nearly lost his new town when its governor, an Italian mercenary, offered to sell it to the French. Unfortunately for the latter Edward got wind of the plot, persuaded the governor to co-operate, and with the Prince of Wales crossed the Channel so secretly that no one knew he was in Calais. When the French arrived to take possession they were ambushed and all taken prisoner. With his accustomed style King Edward, ‘bareheaded save for a chaplet of fine pearls’, entertained his captives to a sumptuous dinner on New Year’s Eve.

In 1350 Edward won yet another victory. The Count of Flanders had allowed the Castilians to assemble a fleet at Sluys, from where they wrought havoc on English merchant shipping and menaced the sea-link with Guyenne. Edward gathered his ships at Sandwich in August and, accompanied by his third son John of Gaunt (who was only ten), sailed to meet the enemy. The Castilian fleet of forty vessels was commanded by Don Carlos de la Cerda—a prince of the royal house of Castile. In a famous passage Froissart describes how Edward appeared to those on board the cog

Thomas,

the same vessel in which he had fought at Sluys ten years earlier. ‘The King stood at his ship’s prow, clad in a jacket of black velvet, and on his head a hat of black beaver that became him right well; and he was then (as I was told by such as were with him that day) as merry as ever he was seen.’ He made his minstrels play on their trumpets a German dance which had just been brought to England by Sir John Chandos, and commanded Chandos to sing with the minstrels, laughing at the result. From time to time he looked up at the mast, for he had put a man in the crow’s nest to warn him when the Castilians were sighted. On seeing the enemy Edward cried, ‘Ho! I see a ship coming and methinks it is a ship of Spain!’ When he saw the whole Castilian fleet he said, ‘I see so many, God help me! that I may not tell them.’ By then it was evening—‘about the hour of vespers’. The King ‘sent for wine and drank thereof, he and all his knights ; then he laced on his helm’.

The battle which ensued—off Winchelsea, but known as Les-Espagnols-sur-Mer—was a far more dangerous and close-fought business than Sluys. The advantage of galleys over cogs has already been emphasized, and the Castilians were armed with stone-throwing catapults, giant crossbows and cannon. They also had the wind in their favour. Both the King and the Prince of Wales had their ships sunk beneath them and only survived by boarding enemy vessels. After a ferocious combat which continued till nightfall, fourteen Castilian galleys—some say more—were captured and their crews thrown overboard, the remaining enemy vessels fleeing. England rejoiced at the news, especially the coastal counties of the south.

But France had already suffered a far worse disaster, the Black Death—bubonic plague—which had broken out in Marseilles and spread all over France during 1348 and 1349. According to one chronicler, the death-toll in Paris alone reached 80,000. People said that the end of the world had come. The King, who obviously believed that God was punishing France for her sins, imposed a somewhat unusual sanitary precaution : he issued an edict against blasphemy. For the first offence a man was to lose a lip, for the second the other lip and for the third the tongue itself. There can have been few unhappier monarchs than Philip VI in the last years of his reign.

However, the plague also crossed the Channel. It appeared in Dorset in August 1348, spreading all over England where it raged until the end of 1349. It is generally believed that about a third of the entire population died. Land was abandoned, rents fell off or were unpaid. In consequence the yield from taxes declined drastically. The resulting shortage of both men and money had a dampening effect, to say the least, on any thoughts of invasion or large-scale military operations by the English and French monarchies.

On 22 August 1350 King Philip of France died at Nogent-le-roi. ‘On the following Thursday his body was buried at Saint-Denis, on the left side of the great altar, his bowels were interred at the Jacobins, at Paris, and his heart at the convent of the Carthusians at Bourgfontaines in Valois.’ He has gone down to history as a lamentable failure. France has never forgiven him for Crécy, while historians blame him for weakening the French monarchy by granting too many privileges and exemptions for ready money. Yet Crécy was a single tactical error. He raised vast armies and kept them in the field by triumphing over an almost inoperable fiscal system, and in his bargains with the local assemblies he made them realize that the English threatened the entire kingdom. Although he lost Calais, he left France a far larger country : in 1349 he bought the town of Montpelier from the King of Majorca, while the same year, after long negotiation, he succeeded in buying the Dauphiné from its last Count or

Dauphin

in the name of his grandson, the future Charles V. This was the biggest acquisition of territory since the reign of St Louis—the frontiers of France had at last reached the Alps. Moreover this grandson, who was to prove one of the greatest of all French kings, would follow many of the policies of Philip VI.

Although Edward III was to take the field again, the victory of Les-Espagnols-sur-Mer marks the end of the period when he was the dominant protagonist in the Hundred Years War. He had shown himself to be a superb soldier and had humiliated his Valois rival. He was no nearer his ambition of gaining the crown of France, but he remained as determined as ever to take their kingdom from the Valois—or a large part of it—and he was ready to wait for the right moment to restart the War, even if someone else was to lead his armies.

3

Poitiers and the Black Prince 1350—1360

Give me an armour of eternal steel! I go to conquer Kings ...

The Raigne of King Edward III

We took our road through the land of Toulouse, where many goodly towns and strongholds were burnt and destroyed, for the land was rich and plenteous.

The Black Prince in 1355

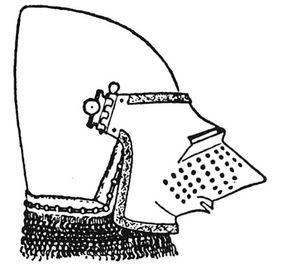

The next stage of the Hundred Years War, from 1350 to 1364, saw the emergence of Philip’s son, King John II of France, and of the Black Prince, Edward III’s son, who eventually took up permanent residence in Guyenne. Edward of Woodstock, Prince of Wales, and traditionally known as the Black Prince (from the colour of his armour), is one of the great heroes of English history. As with most heroes the reality was a little different from the legend, but unquestionably he was a son after Edward III’s heart. In 1350 the Prince was twenty and shared to the full his father’s appetite for military glory. However, he had to contain his warlike spirit in patience for some time, as the conflict of the early 1350s was largely limited to negotiation.

Few negotiators can have been as inept as ‘Jean le Bon’, probably the most stupid of all French kings. Born in 1319, the former Duke of Normandy was by now verging on medieval middle age, a big handsome man with a thick red beard. His ill-merited soubriquet was bestowed on him for prowess in the tournament and pigheaded bravery on the battlefield, but his marked characteristics were blind rage and a tendency to panic. John II’s only other outstanding quality seems to have been a certain charm of manner—when he was on his best behaviour.

Although Edward III had abated none of his ambitions, the years from 1350 to 1355 were (save in Brittany) a low-key period of the War. Either the English King had taken the exact measure of his new opponent and hoped to manoeuvre him into concessions, or else he was waiting for England to recover from the ravages of the Black Death. Professor Perroy considers that ‘Edward III was not unaware of the weaknesses and the panic fear of the new King of France. He took pleasure in prolonging the threat, continually postponed, of a fresh landing.’ All one can say is, however, that apart from a series of truces there is little evidence of constructive diplomatic activity until 1353. Edward then took advantage of Papal mediation to offer to abandon his claim to the French crown in return for Guyenne ‘as his ancestors had held it’ (i.e. with Poitou and the Limousin) and Normandy, together with the suzerainty of Flanders—though he hinted that he was generously prepared to forgo Normandy. The following year he actually increased these demands to include Calais, Anjou and Maine. Almost incredibly King John agreed to them in a provisional treaty at Guines in April 1354. But then John refused to hand over the stipulated territories—possibly he had been merely playing for time.

Meanwhile English intervention in Brittany had been most successful. Their garrisons were mostly in the Celtic west of the duchy, in ports like Brest, Quimperlé and Vannes, though there were some in the French-speaking east, as at Ploermel. The King’s Lieutenant in Brittany, Sir Thomas Dagworth, and his garrison captains launched raid after raid. In 1352 Sir Thomas was ambushed and murdered by a Breton traitor but his successor, Sir Walter Bentley, was quite as vigorous and the same year, using bowmen, won an important victory at Mauron.

The warfare in Brittany was on a comparatively small scale but, to judge from the chronicles, it obviously made a considerable noise among the fighting classes. For contemporaries, if not for history, one of the most important events of the Hundred Years War was the ‘Combat of the Thirty’ —‘a magnificent but murderous kind of tourney’ as Perroy calls it—which tells us a good deal about the mentality of the officer class of 1351. That year the English garrison at Ploermel was attacked by a French force under Robert de Beaumanoir. To avoid a siege the garrison commander, Sir Richard Bamborough, suggested a combat on the open plain before Ploermel between thirty men-at-arms from each side. Bamborough told his knights (who included Bretons and German mercenaries as well as English) to fight in such a way ‘that people will speak of it in future times in halls, in palaces, in public places and elsewhere throughout the world’. They all fought on foot, with swords and halberds, until four of the French and two of the English had been killed and everyone was exhausted. A breathing-space was called but when Beaumanoir, badly wounded, staggered off to find some water, an Englishman mocked at him—‘Beaumanoir, drink thy blood and thy thirst will go off.’ The combat recommenced. It seemed impossible to break the English, who fought in a tight formation, shoulder to shoulder. At last a French knight stole away, quietly mounted his great warhorse and then returned at the charge, knocking his opponents off their feet. The French pounced on the English, killing nine including Bamborough, and taking the rest prisoner. Among the latter were Robert Knollys with his half-brother Hugh Calveley, a pair of whom more will be heard.

Less chivalrous activities in Brittany had continued to make the War popular with all classes of Englishmen. These were the various methods of making money out of the local population. The most profitable was of course ransom —selling a prisoner his freedom. A prince or great nobleman commanded an enormous price, but the market was not restricted to magnates ; a fat burgess or an important cleric could be an almost equally enviable prize. Indeed there was a famous scandal during the siege of Calais when a certain John Ballard was rumoured to have captured the Archdeacon of Paris and smuggled him back to London, where he was supposed to have fetched a mere £50. For ransoming was often more like the kidnap racket of modern times, and small tradesmen and farmers had their price; even plough-men fetched a few pence. Sometimes fortunes were made——Sir John Harleston’s

share

in a French knight taken during Edward’s march through Normandy amounted to no less than £1,500. Nor was the business confined to the upper classes ; the humblest archer, a serf at home perhaps, might suddenly find himself a rich man.

Even Edward himself engaged in the ransom trade, acting as a kind of broker. He bought particularly valuable prisoners from their captors at a reduced price, hoping to recover the full asking-price from the prisoner’s relatives or representatives. The King possessed the administrative machinery for such transactions so it was often well worth the captor’s while to sell to him; in 1347 Sir Thomas Dagworth sold Charles of Blois to the King for 25,000 gold crowns (nearly £5,000) and no doubt Edward made a good profit. Other magnates also acted as ransom brokers, purchasing high-ranking prisoners as a speculation; sometimes, like any other marketable commodity, the prisoners changed hands several times. Calais was to become the centre of this trade. Payment was not necessarily in money but could be in kind—horses, clothing, wine, weapons.