The New Penguin History of the World (139 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

This makes him very different from a monarch of the traditional stamp, even the most modernizing – and, in fact, he was often very conservative in his policies, distrusting innovation. In the end he was a democratic despot, whose authority came from the people, both in the formal sense of the plebiscites, and in the more general one that he had needed (and won) their goodwill to keep his armies in the field. He is thus nearer in style to twentieth-century rulers than to Louis XIV. Yet he shares with that monarch the credit for carrying French international power to an unprecedented height and because of this both of them have retained the admiration of their countrymen. But again there is an important, and twofold, difference: Napoleon not only dominated Europe as Louis XIV never did, but because the Revolution had taken place his hegemony represented more than mere national supremacy, though this fact should not be sentimentalized. The Napoleon who was supposed to be a liberator and a great European was the creation of later legend. The most obvious impact he had on Europe between 1800 and 1814 was the bloodshed and upheaval he brought to every corner of it, often as a consequence of megalomania and personal vanity. But there were also important side-effects, some intentional, some not. They all added up to the further spread and effectiveness of the principles of the French Revolution.

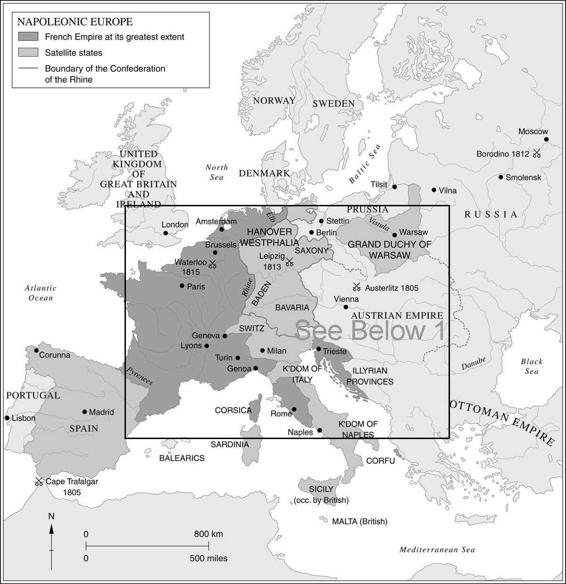

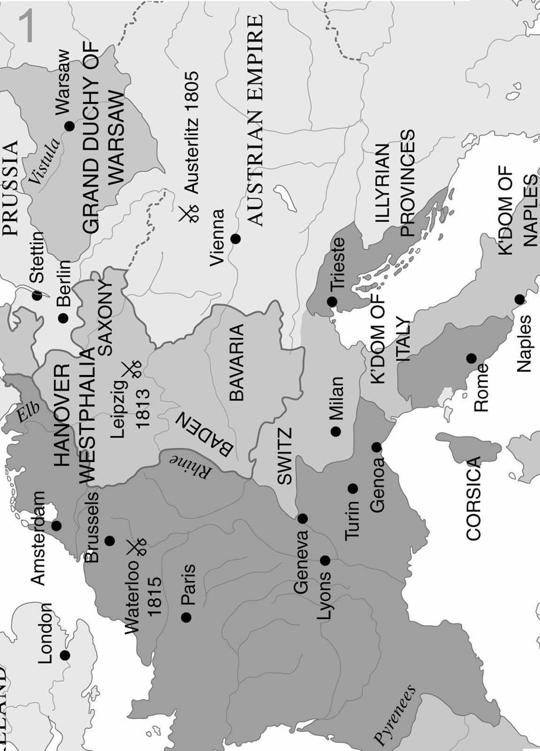

Their most obvious expression was on the map. The patchwork quilt of the European state system of 1789 had undergone some revolutionary revision already before Napoleon took power, when French armies in Italy, Switzerland and the United Provinces had created new satellite republics. But these had proved incapable of survival once French support was withdrawn and it was not until French hegemony was re-established under the Consulate that there appeared a new organization which would have enduring consequences in some parts of Europe.

The most important of these were in west Germany, whose political structure was revolutionized and medieval foundations swept away. German territories on the left bank of the Rhine were annexed to France for the whole of the period from 1801 to 1814, and this began a period of destroying historic German polities. Beyond the river, France provided the plan of a reorganization which secularized the ecclesiastical states, abolished nearly all the free cities, gave extra territory to Prussia, Hanover, Bavaria and Baden to compensate them for losses elsewhere, and abolished the old independent imperial nobility. The practical effect was to diminish the Catholic and Habsburg influence in Germany while strengthening the influence of its larger princely states (especially Prussia). The constitution of the Holy Roman Empire was revised, too, to take account of these changes. In its new form it lasted only until 1806, when another defeat of

the Austrians led to more changes in Germany and its abolition. So came to an end the institutional structure which, however inadequately, had given Germany such political coherence as it had possessed since Ottoman times. A Confederation of the Rhine was now set up, which provided a third force balancing that of Prussia and Austria. Thus were triumphantly asserted the national interests of France in a great work of destruction. Richelieu and Louis XIV would have enjoyed the contemplation of a French frontier on the Rhine with, beyond it, a Germany divided into interests likely to hold one another in check. But there was another side to it; the old structure, after all, had been a hindrance to German consolidation. No future rearrangement would ever contemplate its resurrection. When, finally, the allies came to settle post-Napoleonic Europe, they too provided for a German Confederation. It was different from Napoleon’s. Prussia and Austria were members of it in so far as their territories were German, but there was no going back on the fact of consolidation. More than three hundred political units with different principles of organization in 1789 were reduced to thirty-eight states in 1815.

Reorganization was less dramatic in Italy and its effect less revolutionary. The Napoleonic system provided in the north and south of the peninsula two large units which were nominally independent, while a large part of it (including the papal states) was formally incorporated in France and organized in departments. None of this survived 1815, but neither was there a complete restoration of the old regime. Notably, the ancient republics of Genoa and Venice were left in the tombs to which the armies of the Directory had first consigned them. They were absorbed by bigger states, Genoa by Sardinia, Venice by Austria. Elsewhere in Europe, at the height of Napoleonic power, France had annexed and governed directly a huge block of territory whose coasts ran from the Pyrenees to Denmark in the north and from Catalonia almost without interruption to the boundary between Rome and Naples in the south. Lying detached from it was a large piece of what became Yugoslavia. Satellite states and vassals of varying degrees of real independence, some of them ruled over by members of Napoleon’s own family, divided between them the rest of Italy, Switzerland and Germany west of the Elbe. Isolated in the east was another satellite, the ‘grand duchy’ of Warsaw, which had been created from former Russian territory.

In most of these countries similar administrative practices and institutions provided a large measure of shared experience. That experience, of course, was of institutions and ideas which embodied the principles of the Revolution. They hardly reached beyond the Elbe except in the brief Polish experiment, and thus the French Revolution came to be another

of those great shaping influences which again and again have helped to differentiate eastern and western Europe. Within the French empire, Germans, Italians, Illyrians, Belgians and Dutch were all governed by the Napoleonic legal codes; the bringing of these to fruition was the result of Napoleon’s own initiative and insistence, but the work was essentially that of revolutionary legislators who had never been able in the troubled 1790s to draw up the new codes so many Frenchmen had hoped for in 1789. With the codes went concepts of family, property, the individual, public power and others, which were thus generally spread through Europe. They sometimes replaced and sometimes supplemented a chaos of local, customary, Roman and ecclesiastical law. Similarly, the departmental system of the empire imposed a common administrative practice, service in the French armies imposed a common discipline and military regulation and French weights and measures, based on the decimal system, replaced many local scales. Such innovations exercised an influence beyond the actual limits of French rule, providing models and inspiration to modernizers in other countries. The models were all the more easily assimilated because French officials and technicians worked in many of the satellites while many nationalities other than French were represented in the Napoleonic service.

Such changes took time to produce their full effect, but it was a deep one and was revolutionary. It was by no means necessarily liberal; even if the Rights of Man formally followed the tricolour of the French armies, so did Napoleon’s secret police, quartermasters and customs officers. A more subtle revolution deriving from the Napoleonic impact lay in the reaction and resistance it provoked. In spreading revolutionary principles the French were often putting a rod in pickle for their own backs. Popular sovereignty lay at the heart of the Revolution and it is an ideal closely linked to that of nationalism. French principles said that peoples ought to govern themselves and that the proper unit in which they should do so was the nation: the revolutionaries had proclaimed their own republic ‘one and indivisible’ for this reason. Some of their foreign admirers applied this principle to their own countries; manifestly, Italians and Germans did not live in national states, and perhaps they should. But this was only one side of the coin. French Europe was run for the benefit of France, and it thus denied the national rights of other Europeans. They saw their agriculture and commerce sacrificed to French economic policy, found they had to serve in the French armies, or to receive at the hands of Napoleon French (or quisling) rulers and viceroys. When even those who had welcomed the principles of the Revolution felt such things as grievances, it is hardly surprising that those who had never welcomed them at all should begin to think in terms of national resistance, too. Nationalism in Europe was

given an immense fillip by the Napoleonic era, even if governments distrusted it and felt uneasy about employing it. Germans began to think of themselves as more than Westphalians and Bavarians, and Italians began to believe they were more than Romans or Milanese, because they discerned a common interest against France. In Spain and Russia the identification of patriotic resistance with resistance to the Revolution was virtually complete.

In the end, then, though the dynasty Napoleon hoped to found and the empire he set up both proved ephemeral, his work was of great importance. He unlocked reserves of energy in other countries just as the Revolution had unlocked them in France, and afterwards they could never be quite shut up again. He ensured the legacy of the Revolution its maximum effect and this was his greatest achievement, whether he desired it or not.

His unconditional abdication in 1814 was not quite the end of the story. Just under a year later the emperor returned to France from Elba, where he had lived in a pensioned exile, and the restored Bourbon regime crumbled at a touch. The allies none the less determined to overthrow him, for he had frightened them too much in the past. Napoleon’s attempt to anticipate the gathering of overwhelming forces against him came to an end at Waterloo, on 18 June 1815, when the threat of a revived French empire was destroyed by the Anglo-Belgian and Prussian armies. This time the victors sent him to St Helena, thousands of miles away in the South Atlantic, where he died in 1821. The fright that he had given them strengthened their determination to make a peace that would avoid any danger of a repetition of the quarter-century of almost continuous war which Europe had undergone in the wake of the Revolution. Thus Napoleon still shaped the map of Europe, not only by the changes he had made in it, but also by the fear France had inspired under his leadership.

3

Political Change: A New Europe

Whatever conservative statesmen hoped in 1815, an uncomfortable and turbulent era had only just begun. This can be seen most easily in the way the map of Europe changed in the next sixty years. By 1871, when a newly united Germany took its place among the great powers, most of Europe west of a line drawn from the Adriatic to the Baltic was organized in states claiming to be based on the principle of nationality, even if some minorities still denied it. Even to the east of that line there were some states which were already identified with nations. By 1914 the triumph of nationalism was to go further still, and most of the Balkans would be organized as nation-states, too.

Nationalism, one aspect of a new kind of politics, had origins which went back a long way, to the examples set in Great Britain and some of Europe’s smaller states in earlier times. Yet its great triumphs were to come after 1815, as part of the appearance of a new politics. At their heart lay an acceptance of a new framework of thought which recognized the existence of a public interest greater than that of individual rulers or privileged hierarchies. It also assumed that competition to define and protect that interest was legitimate. Such competition was thought increasingly to require special arenas and institutions; old juridical or courtly forms no longer seemed sufficient to settle political questions.

An institutional framework for this transformation of public life took longer to emerge in some countries than others. Even in the most advanced it cannot be identified with any single set of practices. It always tended, though, to be strongly linked with the recognition and promotion of certain principles. Nationalism was one of them which went most against older principles – that of dynasticism, for instance. It was more and more a commonplace of European political discourse, as the nineteenth century went on, that the interests of those recognized to be ‘historic’ nations should be protected and promoted by governments. This was, of course, wholly compatible with bitter and prolonged disagreement about which

nations were historic, how their interests should be defined, and to what extent they could and should be given weight in statesmen’s decisions.