The New Penguin History of the World (143 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

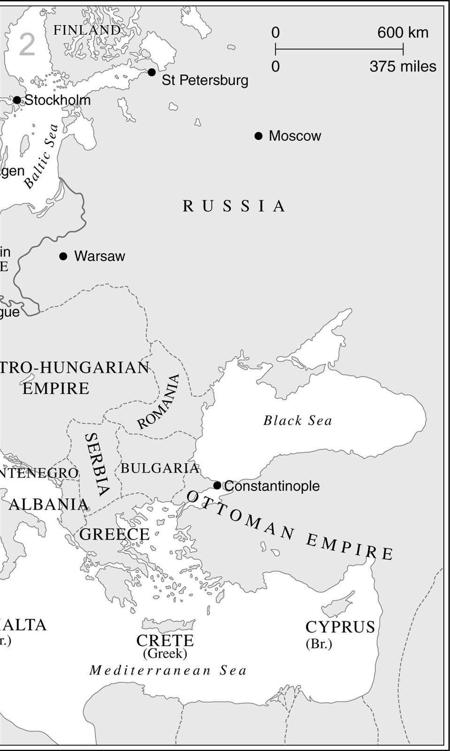

Russia seemed, except in her Polish lands, immune to the disturbances troubling other continental great powers. The French Revolution had been another of those experiences which, like feudalism, Renaissance or Reformation, decisively shaped western Europe and passed Russia by. Although Alexander I, the tsar under whom Russia met the 1812 invasion, had indulged himself with liberal ideas and had even thought of a constitution, nothing seemed to come of this. A formal liberalization of Russian institutions did not begin until the 1860s, and even then its source was not revolutionary contagion. It is true that liberalism and revolutionary ideologies did not quite leave Russia untouched before this. Alexander’s reign had seen something of an opening of a Pandora’s box of ideas and it had thrown up a small group of critics of the regime who found their models in western Europe. Some of the Russian officers who went there with the armies which pursued Napoleon to Paris were led by what they saw and heard to make unfavourable comparisons with their homeland; this was the beginning of Russian political opposition. In an autocracy opposition was bound to mean conspiracy. Some of them took part in the organization of secret societies which attempted a coup amid the uncertainty caused by the death of Alexander in 1825; this was called the ‘Decembrist’ movement. It soon collapsed but only after giving a fright to Nicholas I, a tsar who decisively and negatively affected Russia’s historical destiny at a crucial moment by ruthlessly turning on political liberalism and seeking to crush it. In part because of the immobility which he imposed, Nicholas’s reign influenced Russia’s destiny more than any since that of Peter the Great. A dedicated believer in autocracy, he confirmed the Russian tradition of authoritarian bureaucracy, the management of cultural life, and the rule of the secret police just when the other great conservative powers were, however unwillingly, beginning to move in the opposite direction. There was, of course, much to build on already in the historical legacies which differentiated Russian autocracy from western European monarchy. But there were also great challenges to be met and Nicholas’s reign was a response to these as well as a simple deployment of the old methods of despotism by a man determined to use them.

The ethnic, linguistic and geographical diversity of the empire had begun to pose problems far outrunning the capacity of Muscovite tradition to deal with them. The population of the empire itself more than doubled in the forty years after 1770. This ever-diversifying society none the less remained overwhelmingly backward; its few cities were hardly a part of the vast rural expanses in which they stood and often seemed insubstantial and impermanent, more like huge temporary encampments than settled centres of civilization. The greatest expansion had been to the south and south-east; here new élites had to be incorporated in the imperial structure and to stress the religious ties between the Orthodox was one of the easiest ways to do this. As the conflict with Napoleon had compromised the old prestige of things French and the sceptical ideas of the Enlightenment associated with that country, a new emphasis was now given to religion in the evolution of a new ideological basis for the Russian empire under Nicholas. ‘Official Nationality’, as it was called, was Slavophile and religious in doctrine, bureaucratic in form and strove to give Russia an ideological unity it had lost since outgrowing its historic centre in Muscovy.

The importance of official ideology was from this time one of the great differences between Russia and western Europe. Until the last decade of the twentieth century Russian governments were never to give up their belief in ideology as a unifying force. Yet this did not mean that daily life in the middle of the century, either for the civilized classes or the mass of a backward population, was much different from that of other parts of eastern and central Europe. Yet Russian intellectuals argued about whether Russia was or was not a European country, and this is not surprising; Russia’s roots were different from those of countries further west. What is more, a decisive turn was taken under Nicholas, from the beginning of whose reign possibilities of change which were at least being felt in other dynastic states in the first half of the nineteenth century were simply not allowed to appear in Russia. It was the land

par excellence

of censorship and police. In the long run this was bound to exclude certain possibilities of modernization (though other obstacles rooted in Russian society seem equally important), but in the short run it was highly successful. Russia passed through the whole nineteenth century without revolution; revolts in Russian Poland in 1830–1 and 1863–4 were ruthlessly suppressed, the more easily because Poles and Russians cherished traditions of mutual dislike.

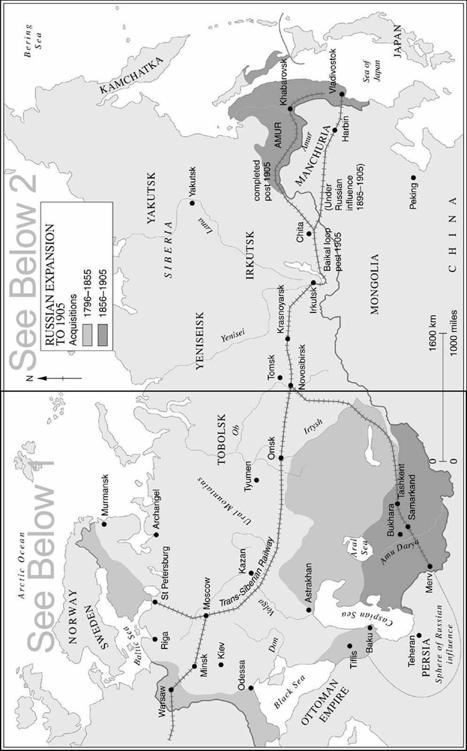

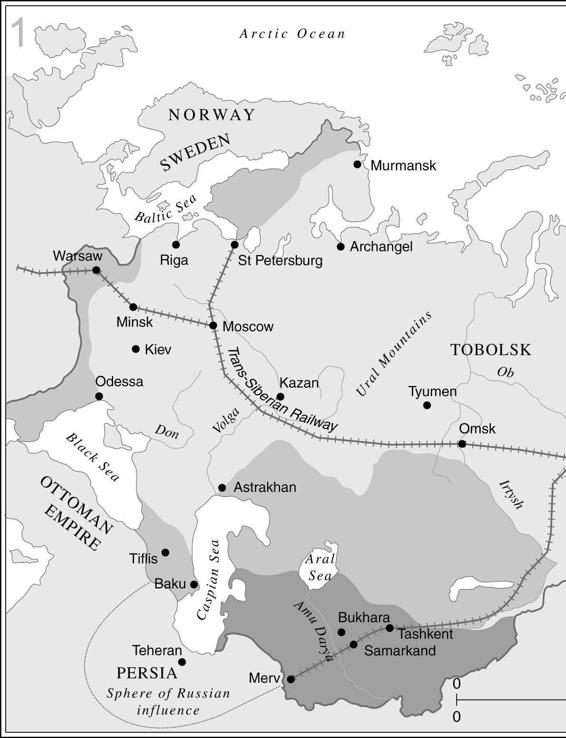

The other side of the coin was the almost continuous violence and disorder of a savage and primitive rural society, and a mounting and more and more violent tradition of conspiracy, which perhaps incapacitated Russia even further for normal politics and the shared assumptions they required. Unfriendly critics variously described Nicholas’s reign as an ice age, a plague zone and a prison, but not for the last time in Russian history the preservation of a harsh and unyielding despotism at home was not incompatible with a strong international role. This rested upon Russia’s huge military superiority. When armies contended with muzzle-loaders and no important weaponry distinguished one from another her vast numbers were decisive. On Russian military strength rested the anti-revolutionary international security system, as 1849 showed. But Russian foreign policy had other successes, too. Pressure was consistently kept up on the central Asian khanates and on China. The left bank of the Amur became Russian and in 1860 Vladivostok was founded. Great concessions were exacted from Persia and during the nineteenth century Russia absorbed Georgia

and a part of Armenia. For a time there was even a determined effort to pursue Russian expansion in North America, where there were forts in Alaska and settlements in northern California until the 1840s.

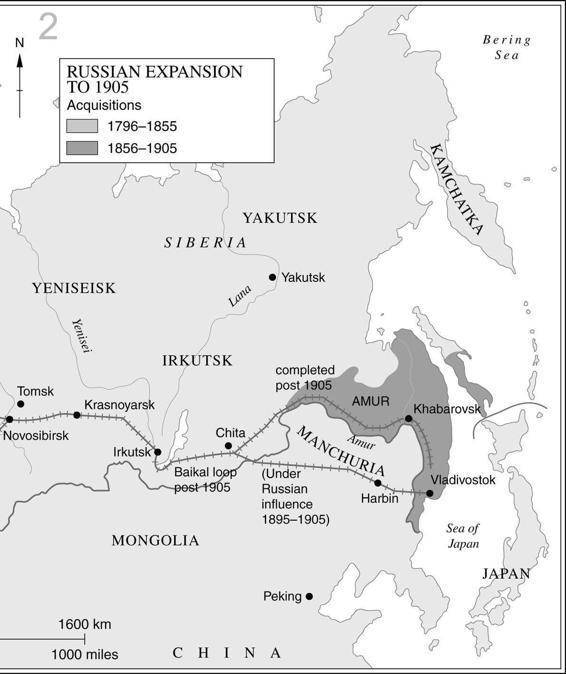

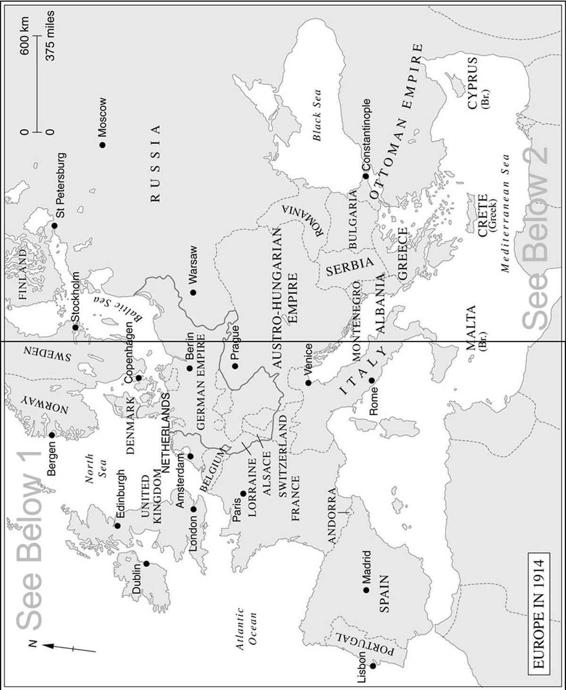

The major effort of Russian foreign policy, nevertheless, was directed to the south-west, towards Ottoman Europe. Wars in 1806–12 and 1828 carried the Russian frontier across Bessarabia to the Pruth and the mouth of the Danube. It was by then clear that the partition of the Ottoman empire in Europe would be as central to nineteenth-century diplomacy as the partition of Poland had been to that of the eighteenth, but there was an important difference: the interests of more powers were involved this time and the complicating factor of national sentiment among the subject peoples of the Ottoman empire would make an agreed outcome much more difficult. As it happened, the Ottoman empire survived far longer than might have been expected, and an eastern question is still bothering statesmen.

Some of these complicating factors led to the Crimean War, which began with a Russian occupation of Ottoman provinces on the lower Danube. In Russia’s internal affairs the war was more important than in those of any other country. It revealed that the military colossus of the 1815 restoration now no longer enjoyed an unquestioned superiority. She was defeated on her own territory and obliged to accept a peace which involved the renunciation for the foreseeable future of her traditional goals in the Black Sea area. Fortunately, in the middle of the war Nicholas I had died. This simplified the problems of his successor; defeat meant that change had to come. Some modernization of Russian institutions was unavoidable if Russia was again to generate a power commensurate with her vast potential, which had become unrealizable within her traditional framework. When the Crimean War broke out there was still no Russian railway south of Moscow. Russia’s once important contribution to European industrial production had hardly grown since 1800 and was now far outstripped by others’. Her agriculture remained one of the least productive in the world and yet her population steadily rose, pressing harder upon its resources. It was in these circumstances that Russia at last underwent radical change. Though less dramatic than many upheavals in the rest of Europe it was in fact more of a revolution than much that went by that name elsewhere, for what was at last uprooted was the institution which lay at the very roots of Russian life, serfdom.