The New Penguin History of the World (153 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The coming of the steamship had its influence, too. It brought India nearer. More Englishmen and Scotsmen began to live and make their careers there. This gradually transformed the nature of the British presence. The comparatively few officers of the eighteenth-century Company had been content to live the lives of exiles, seeking rewards in their commercial opportunities and relaxation in a social life sometimes closely integrated with that of the Indians. They often lived much in the style of Indian gentlemen, some of them taking to Indian dress and food, some to Indian wives and concubines. Reform-minded officials, intent on the eradication of the backward and barbaric in native practice – and in such practices as female infanticide and

suttee

they had good cause for concern – missionaries with a creed to preach which was corrosive of the whole structure of Hindu or Muslim society and, above all, the Englishwomen who arrived to make homes in India while their husbands worked there, often did not approve of the old ways of John Company’s men. They changed the temper of the British community, which drew more and more apart from the

natives, more and more convinced of a moral superiority which sanctioned the ruling of Indians who were culturally and morally inferior. The rulers grew consciously more alien from those they ruled. One of them spoke approvingly of his countrymen as representatives of a ‘belligerent civilization’ and defined their task as ‘the introduction of the essential parts of European civilization into a country densely peopled, grossly ignorant, steeped in idolatrous superstition, unenergetic, fatalistic, indifferent to most of what we regard as the evils of life and preferring the response of submitting to them to the trouble of encountering and trying to remove them’. This robust creed was far from that of the Englishmen of the previous century, who had innocently sought to do no more in India than make money. Now, while new laws antagonized powerful native interests, the British had less and less social contact with Indians; more and more they confined the educated Indian to the lower ranks of the administration and withdrew into an enclosed, but conspicuously privileged, life of their own. Earlier conquerors had been absorbed by Indian society in greater or lesser measure; the Victorian British, thanks to a modern technology which continuously renewed their contacts with the homeland and their confidence in their intellectual and religious superiority, remained immune, increasingly aloof, as no earlier conqueror had been. They could not be untouched by India, as many legacies to the English language and the English breakfast and dinner-table still testify, but they created a civilization that confronted India as a challenge, though not wholly English; ‘Anglo-Indian’ in the nineteenth century was a word applied not to persons of mixed blood, but to Englishmen who made careers in India, and it indicated a cultural and social distinctiveness.

The separateness of Anglo-Indian society from India was made virtually absolute by the appalling damage done to British confidence by the rebellions of 1857 called the Indian Mutiny. Essentially, this was a chain reaction of outbreaks, initiated by a mutiny of Hindu soldiers who feared the polluting effect of using a new type of cartridge, greased with animal fat. This detail is significant. Much of the rebellion was the spontaneous and reactionary response of traditional society to innovation and modernization. By way of reinforcement there were the irritations of native rulers, both Muslim and Hindu, who regretted the loss of their privileges and thought that the chance might have come to recover their independence; the British were after all very few. The response of those few was prompt and ruthless. With the help of loyal Indian soldiers the rebellions were crushed, though not before there had been some massacres of British captives and a British force had been under siege at Lucknow, in rebel territory, for some months.

The Mutiny and its suppression were disasters for British India, though not quite unmitigated. It did not much matter that the Moghul empire was at last formally brought to an end by the British (the Delhi mutineers had proclaimed the last emperor their leader). Nor was there, as later Indian nationalists were to suggest, a crushing of a national liberation movement whose end was a tragedy for India. Like many episodes important in the making of nations, the Mutiny was to be important as a myth and an inspiration; what it was later believed to have been was more important than what it actually was, a jumble of essentially reactionary protests. Its really disastrous and important effect was the wound it gave to British goodwill and confidence. Whatever the expressed intentions of British policy, the consciousness of the British in India was from this time suffused by the memory that Indians had once proved almost fatally untrustworthy. Among Anglo-Indians as well as Indians the mythical importance of the Mutiny grew with time. The atrocities actually committed were bad

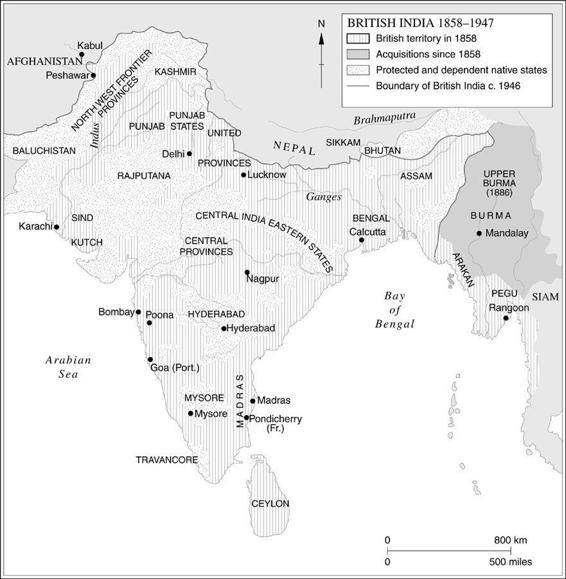

enough, but others, which had never occurred, were also alleged as grounds for a policy of repression and social exclusiveness. Immediately and institutionally, the Mutiny also marked an epoch because it ended the government of the Company. The governor-general now became the queen’s viceroy, responsible to a British cabinet minister. This structure provided the framework of the British Raj for its life of ninety years.

The Mutiny thus changed Indian history, but by thrusting it more firmly in a direction to which it already tended. Another fact, which was equally revolutionary for India, was much more gradual in its effects. This was the nineteenth-century flowering of the economic connection with Great Britain. Commerce was the root of the British presence in the subcontinent and it continued to shape its destiny. The first major development came when India became the essential base for the China trade. Its greatest expansion came in the 1830s and 1840s when, for a number of reasons, access to China became much easier. It was at about the same time that there took place the first rapid rise in British exports to India, notably of textiles, so that, by the time of the Mutiny, a big Indian commercial interest existed which involved many more Englishmen and English commercial houses than the old Company had ever done.

The story of Anglo-Indian trade was now locked into that of the general expansion of British manufacturing supremacy and world commerce. The Suez Canal brought down the costs of shipping goods to Asia by a huge factor. By the end of the century the volume of British trade with India had more than quadrupled. The effects were felt in both countries, but were decisive in India, where a check was imposed on an industrialization which might have gone ahead more rapidly without British competition. Paradoxically, the growth of trade thus delayed India’s modernization and alienation from its own past. But there were other forces at work, too. By the end of the century the framework provided by the Raj and the stimulus of the cultural influences it permitted had already made impossible the survival of a wholly unmodernized India.

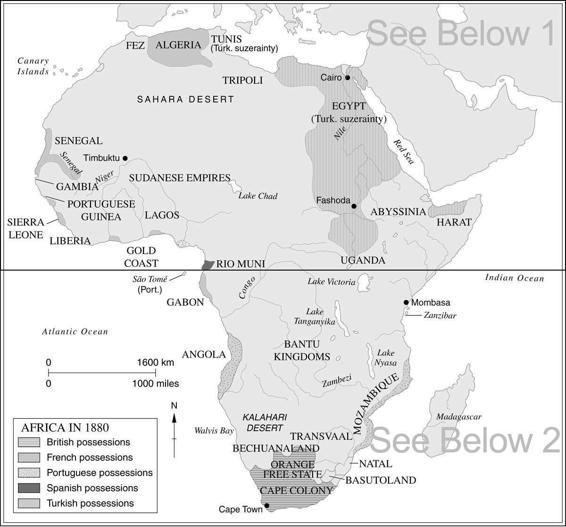

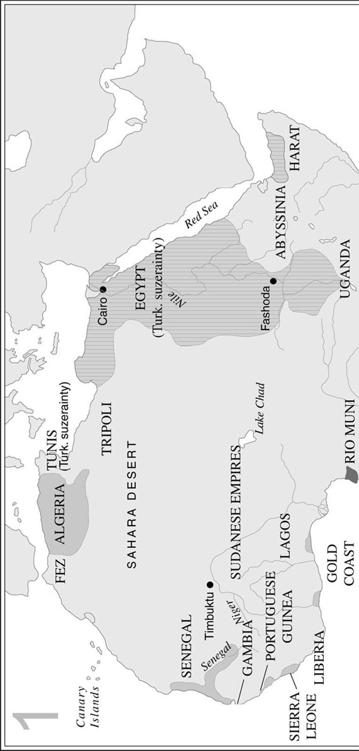

No other nation in the early nineteenth century so extended its imperial possessions as Great Britain, but the French had also made substantial additions to the empire with which they had been left in 1815. In the next half-century France’s interests elsewhere (in West Africa and the South Pacific, for example) were not lost to sight but the first clear sign of a reviving French imperialism came in Algeria. The whole of North Africa was open to imperial expansion by European predators because of the decay there of the formal overlordship of the Ottoman sultan. Right around the southern and eastern Mediterranean coasts the issue was posed of a possible Turkish partition. French interest in the area was natural; it went back to a great extension of the country’s Levant trade in the eighteenth century. But a more precise marker had been the expedition to Egypt under Bonaparte in 1798, which opened the question of the Ottoman succession in its extra-European sphere.

Algeria’s conquest began uncertainly in 1830. A series of wars not only with its native inhabitants but with the sultan of Morocco followed until, by 1870, most of the country had been subdued. This was, in fact, to open a new phase of expansion, for the French then turned their attention to Tunis, which accepted a French protectorate in 1881. To both these sometime Ottoman dependencies there now began a steady flow of European immigrants, not only from France, but from Italy and, later, Spain. This built up substantial settler populations in a few cities which were to complicate the story of French rule. The day was past when the African Algerian might have been exterminated or all but exterminated, like the Aztec, American Indian or Australian aborigine. His society, in any case, was more resistant, formed in the crucible of an Islamic civilization which had once contested so successfully with Christendom. None the less, he

suffered, notably from the introduction of land law which broke up his traditional usages and impoverished the peasant by exposing him to the full blast of market economics.

At the eastern end of the African littoral a national awakening in Egypt led to the emergence there of the first great modernizing nationalist leader outside the European world, Mehemet Ali, pasha of Egypt. Admiring Europe, he sought to borrow its ideas and techniques while asserting his independence of the sultan. When he was later called upon for help by the sultan against the Greek revolution, Mehemet Ali went on to attempt to seize Syria as his reward. This threat to the Ottoman empire provoked an international crisis in the 1830s in which the French took his side. They were not successful, but thereafter French policy continued to interest itself in the Levant and Syria too, an interest which was eventually to bear fruit in the brief establishment in the twentieth century of a French presence in the area.

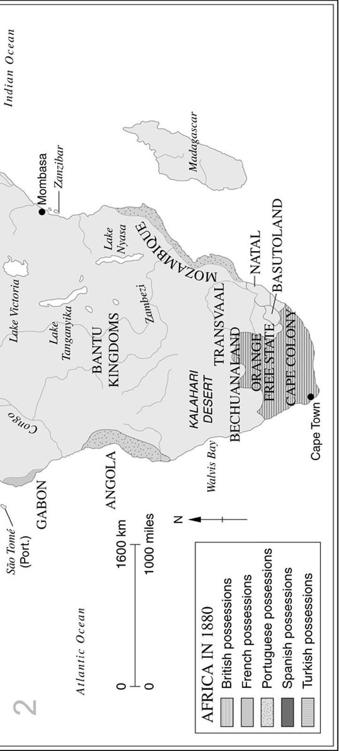

The feeling that Great Britain and France had made good use of their opportunities in the early part of the nineteenth century was no doubt one reason why other powers tried to follow them from 1870 onwards. But envious emulation does not go far as an explanation of the extraordinary suddenness and vigour of what has sometimes been called the ‘imperialist wave’ of the late nineteenth century. Outside Antarctica and the Arctic less than a fifth of the world’s land surface was not under a European flag or that of a country of European settlement by 1914; and of this small fraction only Japan, Ethiopia and Siam enjoyed real autonomy.