The New Penguin History of the World (75 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Persian culture enjoyed a spectacular flowering under Shah Abbas, who built a new capital at Isfahan. Its beauty and luxury astounded European visitors. Literature flourished. The only ominous note was religious. The shah insisted on abandoning the religious toleration which had until now characterized Safavid rule and imposed conversion to Shi’ite views. This did not at once mean the imposition of an intolerant system; that would only come later. But it did mean that Safavid Persia had taken a significant step towards decline and towards the devolution of power into the hands of religious officials.

After Shah Abbas’s death in 1629 events rapidly took a turn for the worse. His unworthy successor did little about this, preferring to withdraw to the seclusion of the harem and its pleasures, while the traditional splendour of the Safavid inheritance cloaked its actual collapse. The Turks took Baghdad again in 1638. In 1664 came the first portents of a new threat:

Cossack raids began to harry the Caucasus and the first Russian mission arrived in Isfahan. Western Europeans had already long been familiar with Persia. In 1507 the Portuguese had established themselves in the port of Ormuz where Ismail levied tribute on them. In 1561 an English merchant reached Persia overland from Russia and opened up Anglo-Persian trade. In the early seventeenth century his connection was well established and by then Shah Abbas had Englishmen in his service. This was the result of his encouragement of relations with the West, where he hoped to find support against the Turk.

The growing English presence was not well received by the Portuguese. When the East India Company opened operations they attacked its agents, but unsuccessfully. A little later the English and Persians joined forces to eject the Portuguese from Ormuz. By this time other European countries were becoming interested, too. In the second half of the seventeenth century the French, Dutch and Spanish all tried to penetrate the Persian trade. The shahs did not rise to the opportunity of playing off one set of foreigners against another.

At the beginning of the eighteenth century Persia was suddenly exposed to a double onslaught. The Afghans revolted and established an independent Sunnite state; religious antagonism had done much to feed their sedition. From 1719 to 1722 the Afghans were at war with the last Safavid shah. He abdicated in that year and an Afghan, Mahmud, took the throne, thus ending Shi’ite rule in Persia. The story must none the less be taken a little further forward, for the Russians had been watching with interest the progress of Safavid decline. The Russian ruler had sent embassies to Isfahan in 1708 and 1718. Then, in 1723, on the pretext of intervention in the succession, the Russians seized Derbent and Baku and obtained from the defeated Shi’ites promises of much more. The Turks decided not to be left out and, having seized Tiflis, agreed in 1724 with the Russians upon a dismemberment of Persia. That once great state seemed to be ending in nightmare. In Isfahan a massacre of possible Safavid sympathizers was carried out by orders of a shah who had now gone mad. There was, before long, to be a last Persian recovery by the last great Asiatic conqueror, Nadir Kali. But though he might restore Persian empire, the days when the Iranian plateau was the seat of a power which could shape events far beyond its borders were over until the twentieth century, and then it would not be armies which gave Iran its leverage.

5

The Making of Europe

If the comparison is with Byzantium or the caliphate, then Europe west of the Elbe was for centuries after the Roman collapse an almost insignificant backwater of world history. The cities in which a small minority of its people lived were built among and of the ruins of what the Romans had left behind; none of them could have approached in magnificence Constantinople, Córdoba, Baghdad or Ch’ang-an. A few of the leading men of its peoples felt themselves a beleaguered remnant and so, in a sense, they were. Islam cut them off from Africa and the Near East. Arab raids tormented their southern coasts. From the eighth century the seemingly inexplicable violence of the Norse peoples we call Vikings fell like a flail time and time again on the northern coasts, river valleys and islands. In the ninth century the eastern front was harried by the pagan Magyars. Europe had to form itself in a hostile, heathen world.

The foundations of a new civilization had to be laid in barbarism and backwardness, which only a handful of men was available to tame and cultivate. Europe would long be a cultural importer. It took centuries before its architecture could compare with that of the classical past, of Byzantium or the Asian empires, and when it emerged it did so by borrowing the style of Byzantine Italy and the pointed arch of the Arabs. For just as long, no science, no school in the West could match those of Arab Spain or Asia. Nor could western Christendom produce an effective political unity or theoretical justification of power such as the eastern empire and the caliphates; for centuries even the greatest European kings were hardly more than barbarian warlords to whom men clung for protection and in fear of something worse.

Had it come from Islam, that something might well have been better. At times, such an outcome must have seemed possible, for the Arabs established themselves not only in Spain but in Sicily, Corsica, Sardinia and the Balearics; men long feared they might go further. They had more to offer than the Scandinavian barbarians, yet in the end the northerners left more of a mark on the kingdoms established by earlier migrants. As for Slavic Christendom and

Byzantium, both were culturally sundered from Catholic Europe and able to contribute little to it. Yet they were a cushion which just saved Europe from the full impact of eastern nomads and of Islam. A Muslim Russia would have meant a very different history for the West.

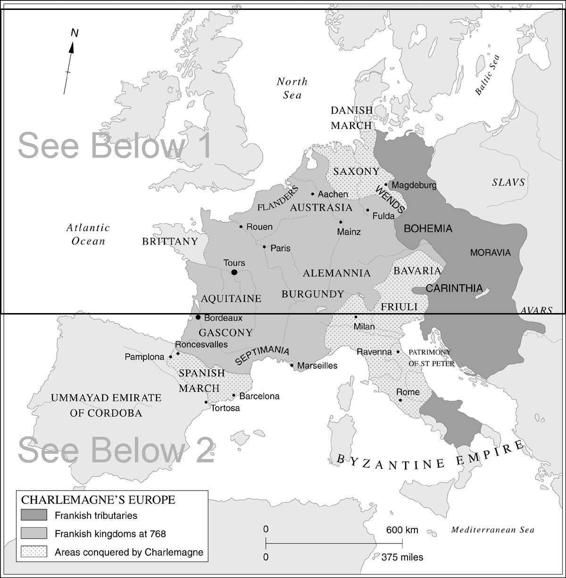

Roughly speaking, western Christendom before

AD

1000 meant half the Iberian peninsula, all modern France and Germany west of the Elbe, Bohemia, Austria, the Italian mainland and England. At the fringes of this area lay barbaric, but Christian, Ireland and Scotland, and the Scandinavian kingdoms. To this area the word ‘Europe’ began to be applied in the tenth century; a Spanish chronicle even spoke of the victors of 732 as ‘European’. The area they occupied was all but landlocked; though the Atlantic was wide open, there was almost nowhere to go in that direction once Iceland was settled by the Norwegians, while the western Mediterranean, the highway to other civilizations and their trade, was an Arab lake. Only a thin channel of sea-borne communication with an increasingly alien Byzantium brought Europe some relief from its introverted, narrow existence. Men grew used to privation rather than opportunity. They huddled together under the rule of a warrior class which they needed for their protection.

In fact, the worst was over in the tenth century. The Magyars were checked, the Arabs were beginning to be challenged at sea, and the northern barbarians were on the road to Christianity. The approach of the year 1000 was no portentous fact for most Europeans; they were unaware of it, for counting by years from the supposed birth of Christ was by no means yet the rule. That year can serve, none the less, very approximately, as the marker of an epoch, whatever the contemporary significance or lack of it, of that date. Not only had the pressures upon Europe begun to relax, but the lineaments of a later, expanding Europe were already hardening. Much of its basic political and social structure was set and its Christian culture had already much of its peculiar flavour. The eleventh century was to begin an era of revolution and adventure, for which the centuries sometimes called the Dark Ages had provided raw materials. As a way to understand how this happened, a good starting-point is the map.

Well before this, three great changes were under way which were to shape the European map we know. One was a cultural and psychological shift away from the Mediterranean, the focus of classical civilization. Between the fifth and eighth centuries, the centre of European life, in so far as there was one, moved to the valley of the Rhine and its tributaries. By preying on the sea-lanes to Italy and by its distraction of Byzantium in the seventh and eighth centuries, Islam, too, helped to throw back the West upon this heartland of a future Europe. The second change was more

positive, a gradual advance of Christianity and settlement in the East. Though far from complete by 1000, the advance guards of Christian civilization had by then long been pushed out well beyond the old Roman frontier. The third change was the slackening of barbarian pressure. The Magyars were checked in the tenth century; the Norsemen who were eventually to provide rulers in England, northern France, Sicily and some of the Aegean came from the last wave of Scandinavian expansion, which was in its final phase in the early eleventh century. Western Europe was no longer to be just a prey to others. True, even two hundred years later, when the Mongols menaced her, it must have been difficult to feel this. None the less, by 1000 she was ceasing to be wholly plastic.

Western Christendom can be considered in three big divisions. In the central area, built around the Rhine valley, the future France and the future Germany were to emerge. Then there was a west Mediterranean littoral civilization, embracing at first Catalonia, the Languedoc and Provence. With time and the recovery of Italy from the barbarian centuries, this extended itself further to the east and south. A third Europe was the somewhat varied periphery in the west, north-west and north where there were to be found the first Christian states of northern Spain, which emerged from the Visigothic period; England, with its independent Celtic and semi-barbarous neighbours, Ireland, Wales and Scotland; and lastly the Scandinavian states. We must not be too categorical about such a picture. There were areas one might allocate to one or the other of these three regions, such as Aquitaine, Gascony and sometimes Burgundy. Nevertheless, these distinctions are real enough to be useful. Historical experience, as well as climate and race, made these regions significantly different, yet of course most men living in them would not have known in which one they lived; they would certainly have been more interested in differences between them and their neighbours in the next village than of those between their region and its neighbour. Dimly aware that they were a part of Christendom, very few of them would have had even an approximate conception of what lay in the awful shadows beyond that comforting idea.

The origin of the heartland of the medieval West was the Frankish heritage. It had fewer towns than the south and they mattered little; a settlement like Paris was less troubled by the collapse of commerce than, say, Milan. Life centred on the soil, and aristocrats were successful warriors turned landowners. From this base, the Franks began the colonization of Germany, protected the Church and hardened and passed on a tradition of kingship whose origins lay somewhere in the magical powers of Merovingian rulers. But for centuries, state structures were fragile things, dependent on strong kings. Ruling was a very personal activity.

Frankish ways and institutions did not help. After Clovis, though there was dynastic continuity, a succession of impoverished and therefore feeble kings led to more independence for landed aristocrats, who warred with one another; they had the wealth which could buy power. One family from Austrasia came to overshadow the Merovingian royal line. It produced Charles Martel, the soldier who turned the Arabs back at Tours in 732 and the supporter of St Boniface, the evangelizer of Germany. This is a considerable double mark to have left on European history (St Boniface said he could not have succeeded without Charles’s support) and it confirmed the alliance of Martel’s house with the Church. His second son, Pepin the Short, was chosen king by the Frankish nobles in 751. Three years later, the pope came to France and anointed him king as Samuel had anointed Saul and David.