The New Penguin History of the World (79 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

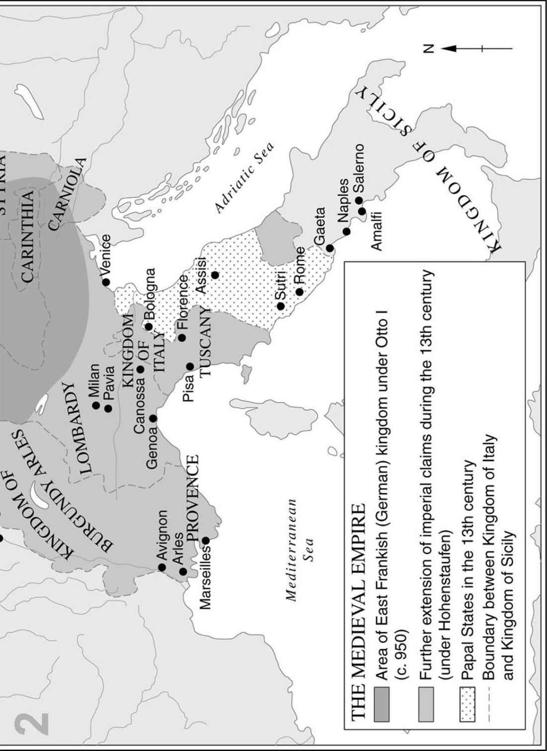

There were some very bad moments in the two and a half centuries after Pepin’s coronation. Rome seemed to have very few cards in its hands and at times only to have exchanged one master for another. Its claim to primacy was a matter of the respect due to the guardianship of St Peter’s bones and the fact that the see was indisputably the only apostolic one in the West: a matter of history rather than of practical power. For a long time the popes could hardly govern effectively even within the temporal domains, for they had neither adequate armed forces nor a civil administration. As great Italian property-owners, they were exposed to predators and blackmail. Charlemagne was only the first, and perhaps he was the most high-minded, of several emperors who made clear to the papacy their views of the respective standing of pope and emperor as guardians of the Church. The Ottonians were great makers and unmakers of popes. The successors of St Peter could not welcome confrontations, for they had too much to lose.

Yet there was another side to the balance sheet, even if it was slow to reveal its full implications. Pepin’s grant of territory to the papacy would in time form the nucleus of a powerful Italian territorial state. In the pope’s coronation of emperors there rested veiled claims, perhaps to the identification of rightful emperors. Significantly, as time passed, popes withdrew from the imperial coronation ceremony (as from that of English and French kings) the use of the chrism, the specially sacred mixture of oil and balsam for the ordination of priests and the coronation of bishops, substituting simple oil. Thus was expressed a reality long concealed but easily comprehensible to an age used to symbols: the pope conferred the crown and the stamp of God’s recognition on the emperor. Perhaps, therefore, he could do so conditionally. Leo’s coronation of Charlemagne, like Stephen’s of Pepin, may have been expedient, but it contained a potent seed. When, as often happened, personal weaknesses and succession disputes disrupted the Frankish kingdoms, Rome might gain ground.

More immediately and practically, the support of powerful kings was needed for the reform of local Churches and the support of missionary enterprise in the East. For all the jealousy of local clergy, the Frankish Church changed greatly; in the tenth century what the pope said mattered a great deal north of the Alps. From the

entente

of the eighth century there emerged gradually the idea that it was for the pope to say what the Church’s policy should be and that the individual bishops of the local Churches

should not pervert it. A great instrument of standardization was being forged. It was there in principle when Pepin used his power as a Frankish king to reform his countrymen’s Church and did so on lines which brought it into step with Rome on questions of ritual and discipline, and further away from Celtic influences.

The balance of advantage and disadvantage long tipped to and fro, the boundaries of the effective powers of the popes ebbing and flowing. Significantly, it was after a further sub-division of the Carolingian heritage so that the crown of Italy was separated from Lotharingia that Nicholas I pressed most successfully the papal claims. A century before, a famous forgery, the ‘Donation of Constantine’, purported to show that Constantine had given to the Bishop of Rome the former dominion exercised by the empire in Italy; Nicholas addressed kings and emperors as if this theory ran everywhere in the West. He wrote to them, it was said, ‘as though he were lord of the world’, reminding them that he could appoint and depose. He used the doctrine of papal primacy against the emperor of the East, too, in support of the Patriarch of Constantinople. This was a peak of pretension which the papacy could not long sustain in practice, for it was soon clear that force at Rome would decide who should enjoy the imperial power the pope claimed to confer. Nicholas’s successor, revealingly, was the first pope to be murdered. None the less, the ninth century laid down precedents, even if they could not yet be consistently followed.

Especially in the collapse of papal authority in the tenth century, when the throne became the prey of Italian factions whose struggles were occasionally cut across by the interventions of the Ottonians, the day-to-day work of safeguarding Christian interests could only be in the hands of the bishops of the local churches. They had to respect the powers that were. Seeking the cooperation and help of the secular rulers, they often moved into positions in which they were all but indistinguishable from royal servants. They were under the thumbs of their secular rulers just as, often, the parish priest was under the thumb of the local lord – and had to share his ecclesiastical proceeds in consequence. This humiliating dependency was later to lead to some of the sharpest papal interventions in the local churches.

The bishops also did much good, in particular, they encouraged missionaries. This had a political side to it. In the eighth century the Rule of St Benedict was well established in England. A great Anglo-Saxon missionary movement, whose outstanding figures were St Willibrord in Frisia and St Boniface in Germany, followed. Largely independent of the east Frankish bishops, the Anglo-Saxons asserted the supremacy of Rome; their converts tended therefore to look directly to the throne of St Peter for religious

authority. Many made pilgrimages to Rome. This papal emphasis died away in the later phases of evangelizing the East, or, rather, became less conspicuous because of the direct work of the German emperors and their bishops. Missions were combined with conquest and new bishoprics were organized as governmental devices.

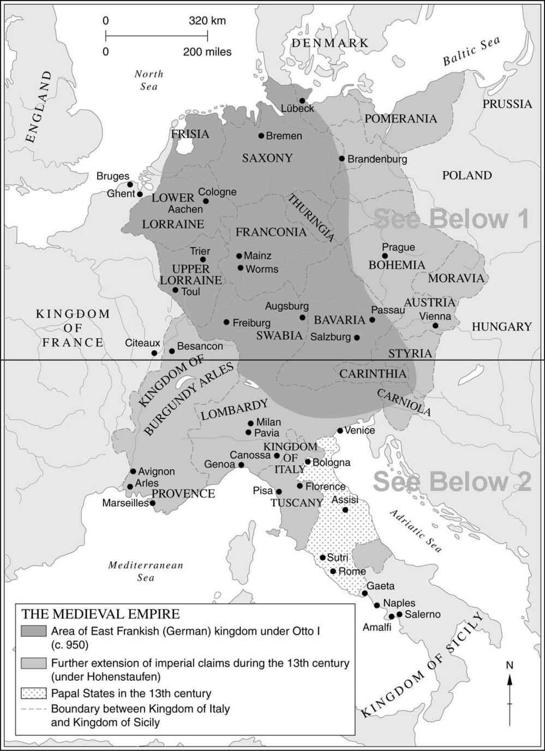

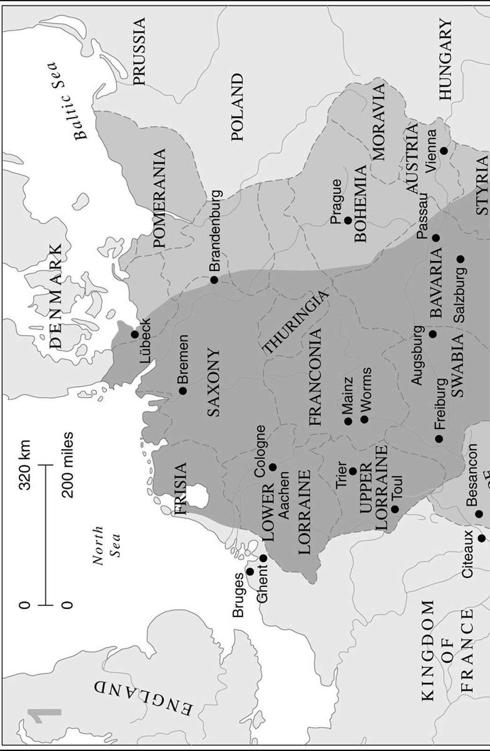

Another great creative movement, that of reform in the tenth century, owed something to the episcopate but nothing to the papacy. It was a monastic movement which enjoyed the support of some rulers. Its essence was the renewal of monastic ideals; a few noblemen founded new houses which were intended to recall a degenerate monasticism to its origins. Most of them were in the old central Carolingian lands, running down from Belgium to Switzerland, west into Burgundy and east into Franconia, the area from which the reform impulse radiated outwards. At the end of the tenth century it began to enlist the support of princes and emperors. Their patronage in the end led to fear of lay dabbling in the affairs of the Church but it made possible the recovery of the papacy from a narrowly Italian and dynastic nullity.

The most celebrated of these foundations was the Burgundian abbey of Cluny, founded in 910. For nearly two and a half centuries it was the heart of reform in the Church. Its monks followed a revision of the Benedictine rule and evolved something quite new, a religious order resting not simply on a uniform way of life, but on a centrally disciplined organization. The Benedictine monasteries had all been independent communities, but the new Cluniac houses were all subordinate to the abbot of Cluny itself; he was the general of an army of (eventually) thousands of monks who only entered their own monasteries after a period of training at the mother house. At the height of its power, in the middle of the twelfth century, more than three hundred monasteries throughout the West – and even some in Palestine – looked for direction to Cluny, whose abbey contained the greatest church in western Christendom after St Peter’s at Rome.

This is to look too far ahead for the present. Even in its early days, though, Cluniac monasticism was disseminating new practices and ideas throughout the Church. This takes us beyond questions of ecclesiastical structure and law, though it is not easy to speak with certainty of all aspects of Christian life in the early Middle Ages. Religious history is especially liable to be falsified by records which sometimes make it very difficult to see spiritual dimensions beyond the bureaucracy. They make it clear, though, that the Church was unchallenged, unique, and that it pervaded the whole fabric of society. It had something like a monopoly of culture. The classical heritage had been terribly damaged and curtailed by the barbarian invasions and the intransigent other-worldliness of early

Christianity: ‘What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?’ Tertullian had asked, but such intransigence had subsided. By the tenth century, what had been preserved of the classical past had been preserved by churchmen, above all by the Benedictines and the copiers of the palace schools who transmitted not only the Bible but Latin compilations of Greek learning. Through their version of Pliny and Boethius a slender line connected early medieval Europe to Aristotle and Euclid.

Literacy was virtually coterminous with the clergy. The Romans had been able to post their laws on boards in public places, confident that enough literate people existed to read them; far into the Middle Ages, even kings were normally illiterate. The clergy controlled virtually all access to such writing as there was. In a world without universities, only a court or church school offered the chance of letters beyond what might be offered, exceptionally, by an individual cleric-tutor. The effect of this on all the arts and intellectual activity was profound; culture was not just related to religion but took its rise only in the setting of overriding religious assumptions. The slogan ‘art for art’s sake’ could never have made less sense than in the early Middle Ages. History, philosophy, theology, illumination, all played their part in sustaining a sacramental culture, but, however narrowed it might be, the legacy they transmitted, in so far as it was not Jewish, was classical.

In danger of dizziness on such peaks of cultural generalization, it is salutary to remember that we can know very little directly about what must be regarded both theologically and statistically as much more important than this and, indeed, as the most important of all the activities of the Church. This is the day-to-day business of exhorting, teaching, marrying, baptizing, shriving and praying, the whole religious life of the secular clergy and laity which centred about the provision of the major sacraments. The Church was in these centuries deploying powers which often cannot have been distinguished clearly by the faithful from those of magic. It used them to drill a barbaric world into civilization. It was enormously successful and yet we have almost no direct information about the process except at its most dramatic moments, when a spectacular conversion or baptism reveals by the very fact of being recorded that we are in the presence of the untypical.

Of the social and economic reality of the Church we know much more. The clergy and their dependants were numerous and the Church controlled much of society’s wealth. The Church was a great landowner. The revenues which supported its work came from its land and a monastery or chapter of canons might have very large estates. The roots of the Church were

firmly sunk in the economy of the day and to begin with that implied something very primitive indeed.

Difficult though it is to measure exactly, there are many symptoms of economic regression in the West at the end of antiquity. Not everyone felt the setback equally. The most developed economic sectors went under most completely. Barter replaced money and a money economy emerged again only slowly. The Merovingians began to coin silver, but for a long time there was not much coin – particularly coin of small denominations – in circulation. Spices disappeared from ordinary diet; wine became a costly luxury; most people ate and drank bread and porridge, beer and water. Scribes turned to parchment, which could be obtained locally, rather than papyrus, now hard to get; this turned out to be an advantage, for minuscule was possible on parchment, and had not been on papyrus, which required large, uneconomical strokes, but none the less it reflects difficulties within the old Mediterranean economy. Though recession often confirmed the self-sufficiency of the individual estate, it ruined the towns. The universe of trade also disintegrated from time to time because of war. Contact was maintained with Byzantium and further Asia, but the western Mediterranean’s commercial activity dwindled during the seventh and eighth centuries as the Arabs seized the North African coast. Later, thanks again to the Arabs, it was partly revived (one sign was a brisk trade in slaves, many of whom came from eastern Europe, from the Slav peoples who thus gave their name to a whole category of forced labour). In the north, too, there was a certain amount of exchange with the Scandinavians, who were great traders. But this did not matter to most Europeans, for whom life rested on agriculture.