The New Penguin History of the World (72 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

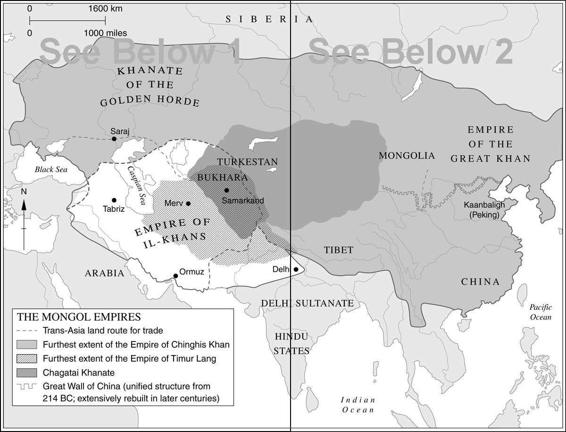

The Mamelukes had another great achievement to their credit by that time. It was they who finally halted the tide of a conquest far more threatening than that of the Franks, when it had been rising for more than half a century. This was the onslaught of the Mongols, whose history makes nonsense of chronological and territorial divisions. In an astonishingly short time this nomadic people drew into their orbit China, India, the Near East and Europe and left ineffaceable marks behind them. Yet there is no physical focus for their history except the felt tents of their ruler’s encampment; they blew up like a hurricane to terrify half a dozen civilizations, slaughtered and destroyed on a scale the twentieth century alone has emulated, and then disappeared almost as suddenly as they came. They demand to be considered alone as the last and most terrible of the nomadic conquerors.

Twelfth-century Mongolia is as far back as a search for their origins need go. A group of peoples speaking the languages of the family called Mongol, who had long demanded the attention of Chinese governments, then lived there. Generally, China played off one of them against another

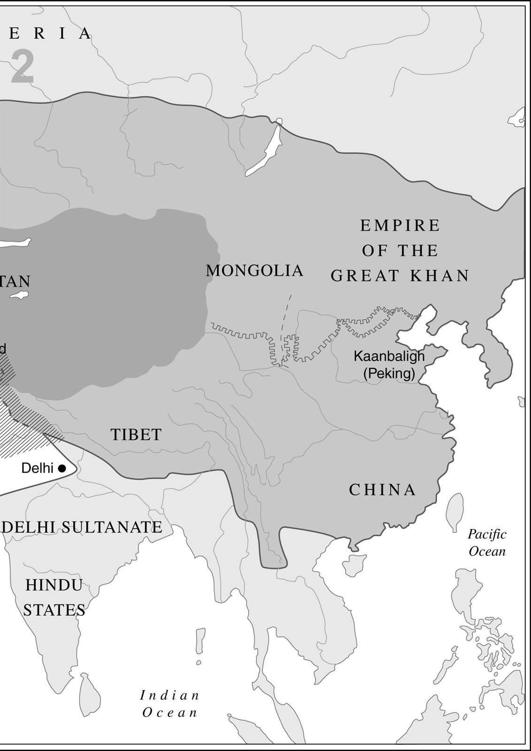

in the interests of its own security. They were barbarians, not much different in their cultural level from others who have already crossed these pages. Two tribes among them, the Tatars and that which became known as the Mongols, competed and on the whole the Tatars had the best of it. They drove one young Mongol to extremes of bitterness and self-assertion. The date of his birth is uncertain, but in the 1190s he became khan to his people. A few years later he was supreme among the Mongol tribes and was acknowledged as such by being given the title of Chinghis Khan. By an Arabic corruption of this name he was to become known in Europe as Genghis Khan. He extended his power over other peoples in central Asia and in 1215 defeated (though he did not overthrow) the Chin state in northern China and Manchuria. This was only the beginning. By the time of his death, in 1227, he had become the greatest conqueror the world has ever known.

He seems unlike all earlier nomad warlords. Chinghis genuinely believed he had a mission to conquer the world. Conquest, not booty or settlement, was his aim and what he conquered he often set about organizing in a systematic way. This led to a structure which deserves the name ‘empire’ more than do most of the nomadic polities. He was superstitious, tolerant of religions other than his own paganism and, said one Persian historian, ‘used to hold in esteem beloved and respected sages and hermits of every tribe, considering this a procedure to please God’. Indeed, he seems to have held that he was himself the recipient of a divine mission. This religious eclecticism was of the first importance, as was the fact that he and his followers (except for some Turks who joined them) were not Muslim, as the Seljuks had been when they arrived in the Near East. Not only was this a matter of moment to Christians and Buddhists – there were both Nestorians and Buddhists among the Mongols – but it meant that the Mongols were not identified with the religion of the majority in the Near East.

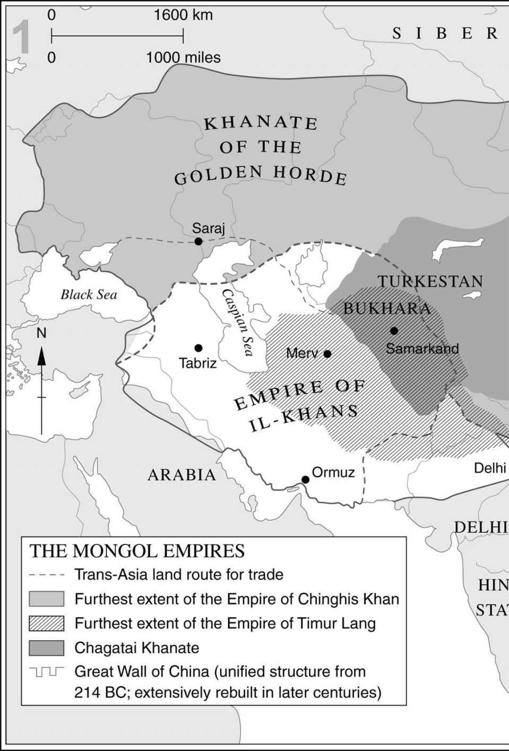

In 1218 Chinghis Khan turned to the west and the era of Mongol invasions opened in Transoxiana and northern Iran. He never acted carelessly, capriciously, or without premeditation, but it may well be that the attack was provoked by the folly of a Muslim prince who killed his envoys. From there Chinghis went on to a devastating raid into Persia, followed by a swing northward through the Caucasus into south Russia, and returned, having made a complete circuit of the Caspian.

All this was accomplished by 1223. Bokhara and Samarkand were sacked with massacres of the townspeople which were meant to terrify others who contemplated resistance. (Surrender was always the safest course with the Mongols and after it several minor peoples were to survive with nothing worse than the payment of tribute and the arrival of a Mongol

governor.) Transoxiana never recovered its place in the life of Islamic Iran after this. Christian civilization was given a taste of Mongol prowess by the defeat of the Georgians in 1221 and of the southern Russian princes two years later. Even these alarming events were only the overture to what was to follow.

Chinghis died in the East in 1227, but his son and successor returned to the West after completing the conquest of northern China. In 1236 his armies poured into Russia. They took Kiev and settled on the lower Volga, from where they organized a tributary system for the Russian principalities they had not occupied. Meanwhile they raided Catholic Europe. The Teutonic knights, the Poles and the Hungarians all went down before them. Cracow was burnt and Moravia devastated. A Mongol patrol crossed into Austria, while the pursuers of the king of Hungary chased him through Croatia and finally reached Albania before they were recalled.

The Mongols left Europe because of dissension among their leaders and the arrival of the news of the death of the khan. A new one was not chosen until 1246. A Franciscan friar attended the ceremony (he was there as an emissary of the pope); so did a Russian grand duke, a Seljuk sultan, the brother of the Abbuyid sultan of Egypt, an envoy from the Abbasid caliph, a representative of the king of Armenia, and two claimants to the Christian throne of Georgia. The election did not solve the problems posed by dissension among the Mongols and it was not until another Great Khan was chosen (after his predecessor’s death had ended a short reign) that the stage was set for another Mongol attack.

This time it fell almost entirely upon Islam, and provoked unwarranted optimism among Christians who noted also the rise of Nestorian influence at the Mongol court. The area nominally still subject to the caliphate had been in a state of disorder since Chinghis Khan’s campaign. The Seljuks of Rum had been defeated in 1243 and were not capable of asserting authority. In this vacuum, relatively small and local Mongol forces could be effective and the Mongol empire relied mainly upon vassals among numerous local rulers.

The campaign was entrusted to the younger brother of the Great Khan and began with the crossing of the Oxus on New Year’s Day 1256. After destroying the notorious sect of the Assassins

en route

, he moved on Baghdad, summoning the caliph to surrender. The city was stormed and sacked and the last Abbasid caliph murdered – because there were superstitions about shedding his blood he is supposed to have been rolled up in a carpet and trampled to death by horses. It was a black moment in the history of Islam as, everywhere, Christians took heart and anticipated the overthrow of their Muslim overlords. When, the following year, the Mongol offensive

was launched against Syria, Muslims were forced to bow to the cross in the streets of a surrendered Damascus and a mosque was turned into a Christian church. The Mamelukes of Egypt were next on the list for conquest when the Great Khan died. The Mongol commander in the West favoured the succession of his younger brother, Kubilai, far away in China. But he was distracted and withdrew many of his men to Azerbaijan to wait on events. It was on a weakened army that the Mamelukes fell at the Goliath Spring near Nazareth on 3 September 1260. The Mongol general was killed, the legend of Mongol invincibility was shattered and a turning-point in world history was reached. For the Mongols the age of conquest was over and that of consolidation had begun.

The unity of Chinghis Khan’s empire was at an end. After civil war the legacy was divided among the princes of his house, under the nominal supremacy of his grandson Kubilai, Khan of China, who was to be the last of the Great Khans. The Russian khanate was divided into three: the khanate of the Golden Horde ran from the Danube to the Caucasus and to the east of it lay the ‘Cheibanid’ khanate in the north (it was named after its first khan) and that of the White Horde in the south. The khanate of Persia included much of Asia Minor, and stretched across Iraq and Iran to the Oxus. Beyond that lay the khanate of Turkestan. The quarrels of these states left the Mamelukes free to mop up the crusader enclaves and to take revenge upon the Christians who had compromised themselves by collaboration with the Mongols.

In retrospect it is still far from easy to understand why the Mongols were so successful for so long. In the west they had the advantage that there was no single great power, such as Persia or the eastern Roman empire had been, to stand up to them, but in the east they defeated China, undeniably a great imperial state. It helped, too, that they faced divided enemies; Christian rulers toyed with the hope of using Mongol power against the Muslim and even against one another, while any combination of the Christian civilizations with China against the Mongols was inconceivable given Mongol control of communication between the two. Their tolerance of religious diversity, except during the period of implacable hatred of Islam, also favoured the Mongols; those who submitted peacefully had little to fear. Would-be resisters could contemplate the ruins of Bokhara or Kiev, or the pyramids of skulls where there had been Persian cities; much of the Mongol success must have been a result of the sheer terror which defeated many of their enemies before they ever came to battle. In the last resort, though, simple military skill explained their victories. The Mongol soldier was tough, well trained and led by generals who exploited all the advantages which a fast-moving cavalry arm could give them. Their mobility

was in part the outcome of the care with which reconnaissance and intelligence work was carried out before a campaign. The discipline of their cavalry and their mastery of the techniques of siege warfare (which, none the less, the Mongols preferred to avoid) made them much more formidable than a horde of nomadic freebooters. As conquests continued, too, the Mongol army was recruiting specialists among its captives; by the middle of the thirteenth century there were many Turks in its ranks.

Though his army’s needs were simple, the empire of Chinghis Khan and, in somewhat less degree, of his successors was an administrative reality over a vast area. One of the first innovations of Chinghis was the reduction of Mongol language to writing, using the Turkish script. This was done by a captive. Mongol rule always drew willingly upon the skills made available to it by its conquests. Chinese civil servants organized the conquered territories for revenue purposes; the Chinese device of paper money, when introduced by the Mongols into the Persian economy in the thirteenth century, brought about a disastrous collapse of trade, but the failure does not make the example of the use of alien techniques less striking.

In so great an empire, communications were the key to power. A network of post-houses along the main roads looked after rapidly moving messengers and agents. The roads helped trade too, and for all their ruthlessness to the cities which resisted them, the Mongols usually encouraged rebuilding and the revival of commerce, from the taxation of which they sought revenue. Asia knew a sort of

Pax Mongolica

. Caravans were protected against nomadic bandits by the policing of the Mongols, poachers turned gamekeepers. The most successful nomads of all, they were not going to let other nomads spoil their game. Land trade was as easy between China and Europe during the Mongol era as at any time; Marco Polo is the most famous of Europe’s travellers to the Far East in the thirteenth century and by the time he went there the Mongols had conquered China, but before he was born his father and uncle had begun travels in Asia which were to last years. They were both Venetian merchants and were sufficiently successful to set off again almost as soon as they got back, taking the young Marco with them. By sea, too, China’s trade was linked with Europe, through the port of Ormuz on the Persian Gulf, but it was the land-routes to the Crimea and Trebizond which carried most of the silks and spices westward and provided the bulk of Byzantine trade in its last centuries. The land-routes depended on the khans and, significantly, the merchants were always strong supporters of the Mongol regime.