The New Penguin History of the World (41 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

None the less, this qualification made, the erosion of time has allowed a beauty of form which is almost unequalled to emerge from the superficial experience. There is no possibility here of discounting the interplay of judgement of the object with standards of judgement which derive ultimately from the object itself. It remains simply true that to have originated an art that has spoken so deeply and powerfully to men’s minds across such ages is itself not easily interpreted except as evidence of an unsurpassed artistic greatness and an astonishing skill in giving it expression.

This quality is also present in Greek sculpture. Here, too, the presence of good stone was an advantage, and the original influence of oriental, often Egyptian, models important. Like pottery, the eastern models once absorbed, sculpture evolved towards greater naturalism. The supreme subject of the Greek sculptors was the human form, portrayed no longer as a memorial or cult object, but for its own sake. Again it is not always possible to be sure of the finished statue the Greeks saw; these figures were often gilded, painted or decorated with ivory and precious stones. Some bronzes have undergone looting or melting down, so that the preponderance of stone may itself be misleading. Their evidence, though, records a clear evolution. We begin with statues of gods and of young men and women whose identity is often unknown, simply and symmetrically presented in poses not too far removed from those of the Orient. In the classical figures of the fifth century, naturalism begins to tell in an uneven distribution of weight and the abandonment of the simple frontal stance and to evolve towards the mature, human style of Praxiteles and the fourth century in which the body – and for the first time the female nude – is treated.

A great culture is more than a mere museum and no civilization can be reduced to a catalogue. For all its élite quality, the achievement and importance of Greece comprehended all sides of life; the politics of the city-state, a tragedy of Sophocles and a statue by Phidias are all part of it. Later ages grasped this intuitively, happily ignorant of the conscientious discrimination which historical scholarship was eventually to make possible between periods and places. This was a fruitful error, because in the end what Greece was to be thought to be was as important to the future as what she was. The meaning of the Greek experience was to be represented and reinterpreted, and ancient Greece was to be rediscovered and reconsidered and, in different ways, reborn and re-used, for more than two thousand years. For all the ways in which reality had fallen short of later

idealization and for all the strength of its ties with the past, Greek civilization was quite simply the most important extension of humanity’s grasp of its destiny down to that time. Within four centuries, Greece had invented philosophy, politics, most of arithmetic and geometry, and the categories of western art. It would be enough, even if her errors too had not been so fruitful. Europe has drawn interest on the capital Greece has laid down ever since, and through Europe the rest of the world has traded on the same account.

4

The Hellenistic World

The history of Greece rapidly becomes less interesting after the fifth century. It is also less important. What remains important is the history of Greek civilization and the shape of this, paradoxically, was determined by a kingdom in northern Greece which some said was not Greek at all: Macedon. In the second half of the fourth century it created an empire bigger than any yet seen, the legatee of both Persia and the city-states. It organized the world we call Hellenistic because of the preponderance and uniting force within it of a culture, Greek in inspiration and language. Yet Macedon was a barbarous place, perhaps centuries behind Athens in the quality of its life and culture.

The story begins with the decline of Persian power. Persian recovery in alliance with Sparta had masked important internal weaknesses. One of them is commemorated by a famous book, the

Anabasis

of Xenophon, the story of the long march of an army of Greek mercenaries back up the Tigris and across the mountains to the Black Sea after an unsuccessful attempt on the Persian throne by a brother of the king. This was only a minor and subsidiary episode in the important story of Persian decline, an offshoot of one particular crisis of internal division. Throughout the fourth century that empire’s troubles continued, with province after province (among them Egypt which won its independence as early as 404 and held it for sixty years) slipping out of control. A major revolt by the western satraps took a long time to master and though in the end imperial rule was restored the cost had been great. When at last reimposed, Persian rule was often weak.

One ruler tempted by the possibilities of this decline was Philip II of Macedon, a not very highly regarded northern kingdom whose power rested on a warrior aristocracy; it was a rough, tough society, its rulers still somewhat like the warlords of Homeric times, their power resting more on personal ascendancy than institutions. Whether this was a state which was a part of the world of the Hellenes was disputed; some Greeks thought Macedonians barbarians. On the other hand, their kings claimed

descent from Greek houses (one going back to Heracles) and their claim was generally recognized. Philip himself sought status; he wanted Macedon to be thought of as Greek. When he became regent of Macedon in 359

BC

he began a steady acquisition of territory at the expense of other Greek states. His ultimate argument was an army which became by the end of his reign the best-trained and organized in Greece. The Macedonian military tradition had emphasized heavy, armoured cavalry, and this continued to be a major arm. Philip added to this tradition the benefit of lessons about infantry he had drawn while a hostage at Thebes in his youth. From hoplite tactics he evolved a new weapon, the sixteen-deep phalanx of pikemen. The men in its ranks carried pikes twice as long as a hoplite spear and they operated in a more open formation, pike shafts from the second and third ranks running between men in the front to present a much denser array of weapons for the charge. Another advantage of the Macedonians was a grasp of siege-warfare techniques not shown by other Greek armies; they had catapults which made it possible to force a besieged town’s defenders to take cover while battering-rams, mobile towers and mounds of earth were brought into play. Such things had previously been seen only in the armies of Assyria and their Asian successors. Finally, Philip ruled a fairly wealthy state, its riches much increased once he had acquired the gold-mines of Mount Pangaeum, though he spent so much that he left huge debts.

He used his power first to ensure the effective unification of Macedon itself. Within a few years the infant for whom he was regent was deposed and Philip was elected king. Then he began to look to the south and north-east. In these areas expansion sooner or later meant encroachment upon the interests and position of Athens. Her allies in Rhodes, Cos, Chios and Byzantium placed themselves under Macedonian patronage. Another, Phocis, went down in a war in which Athens had egged her on but failed to give effective support. Although Demosthenes, the last great agitator of Athenian democracy, made himself a place in history (still recalled by the word ‘philippic’) by warning his countrymen of the dangers they faced, he could not save them. When the war between Athens and Macedon (355–346

BC

) at last ended, Philip had won not only Thessaly, but had established himself in central Greece and controlled the pass of Thermopylae.

His situation favoured designs on Thrace and this implied a return of Greek interest towards Persia. One Athenian writer advocated a Hellenic crusade to exploit Persia’s weakness (in opposition to Demosthenes who continued to denounce the Macedonian ‘barbarian’), and once more plans were made to liberate the Asian cities, a notion attractive enough to bear fruit in a reluctant League of Corinth formed by the major Greek states

other than Sparta in 337

BC

. Philip was its president and general and it was somewhat reminiscent of the Delian League; the apparent independence of its members was a sham, for they were Macedonian satellites. Though the culmination of Philip’s work and reign (he was assassinated the following year), it had only come into being after Macedon had defeated the Athenians and Thebans again in 338

BC

. The terms of peace imposed by Philip were not harsh, but the League had to agree to go to war with Persia under Macedonian leadership. There was one more kick of Greek independence after Philip’s death, but his son and successor Alexander crushed the Greek rebels as he did others in other parts of his kingdom. Thebes was then razed to the ground and its population enslaved (335

BC

).

This was the real end of four centuries of Greek history. During this period civilization had been created and sheltered by the city-state, one of the most successful political forms the world has ever known. Now, not for the first time nor the last, the future seemed to belong to the bigger battalions, the bigger organizations. Mainland Greece was from this time a political backwater under Macedonian governors and garrisons. Like his father, Alexander sought to conciliate the Greeks by giving them a large measure of internal self-government in return for adherence to his foreign policy. This was always to leave some Greeks, notably the Athenian democrats, unreconciled. When Alexander died, Athens once more tried to organize an anti-Macedonian coalition. The results were disastrous. A part of the price of defeat was the replacement of democracy by oligarchy at Athens (322

BC

); Demosthenes fled to an island off the coast, seeking sanctuary in the temple of Poseidon there, but poisoned himself when the Macedonians came for him. A Macedonian governor henceforth ruled the Peloponnese.

Alexander’s reign had thus begun with difficulties, but once they were surmounted, he could turn his attention to Persia. In 334

BC

he crossed to Asia at the head of an army of which a quarter was drawn from Greece. There was more than idealism in this; aggressive war might also be prudent, for the fine army left by Philip had to be paid if it was not to present a threat to a new king, and conquest would provide the money. He was twenty-two years old and before him lay a short career of conquest so brilliant that it would leave his name a myth down the ages and provide a setting for the widest expansion of Greek culture. He drew the city-states into a still wider world.

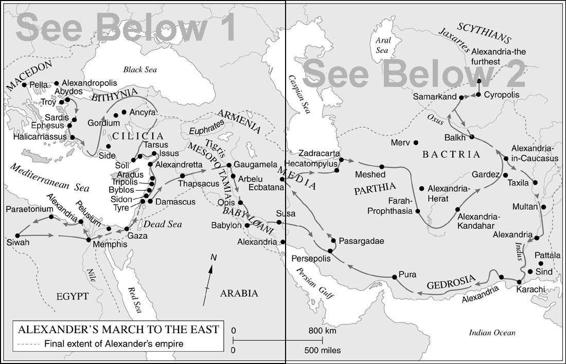

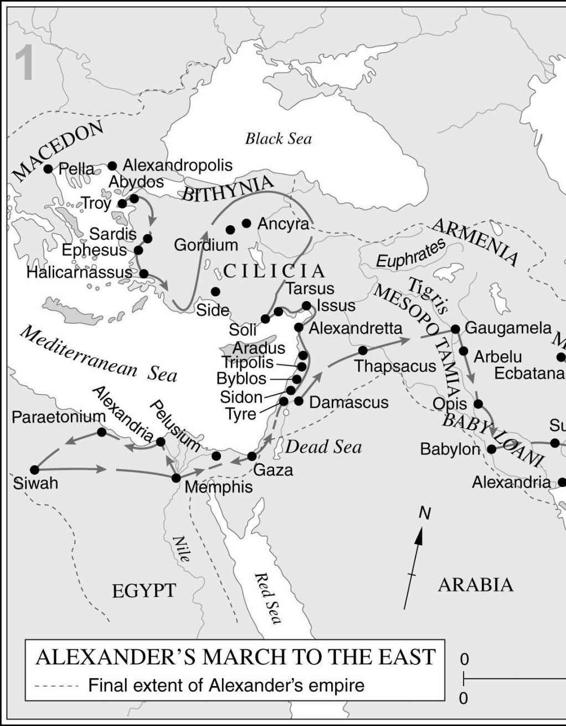

The story is simple to summarize. Legend says that after crossing to Asia Minor he cut the Gordian Knot. He then defeated the Persians at the battle of Issus. This was followed by a campaign which swept south through Syria, destroying Tyre on the way, and eventually to Egypt, where Alexander founded the city still bearing his name. In every battle he was his own best soldier and he was wounded several times in the mêlée. He pushed into the desert, interrogated the oracle at Siwah and then went back into Asia to inflict a second and decisive defeat on Darius III in 331

BC

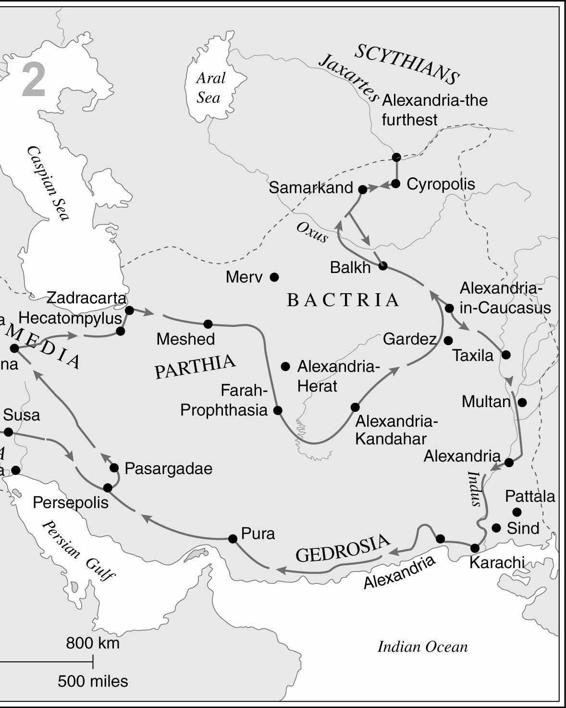

. Persepolis was sacked and burnt and Alexander proclaimed successor to the Persian throne; Darius was murdered by one of his satraps the next year. On went Alexander, pursuing the Iranians of the north-east into Afghanistan (where Kandahar is another of the many cities which commemorate his name) and penetrating a hundred miles or so beyond the Indus into the Punjab. Then he turned back because his army would go no further. It was tired and having defeated an army with 200 elephants may have been disinclined to face the further 5000 reported to be waiting for it in the Ganges valley. Alexander returned to Babylon. There he died in 323

BC

, thirty-two years old and just ten years after he had left Macedon.