The New Penguin History of the World (37 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

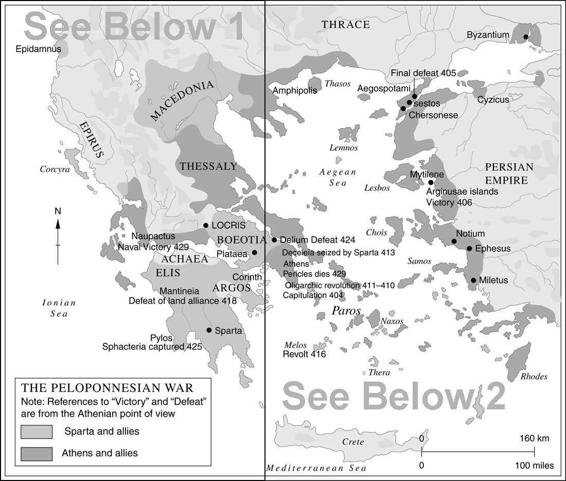

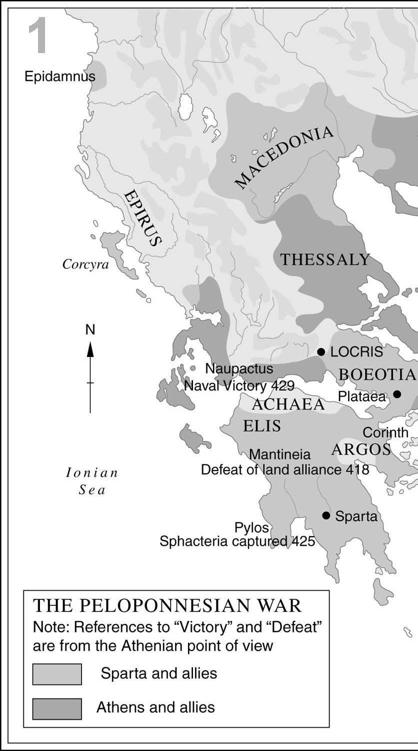

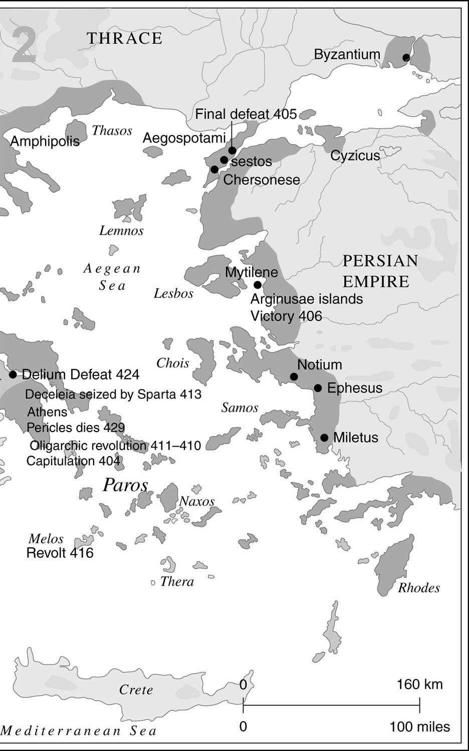

It lasted, with interruptions, twenty-seven years, until 404

BC

. Essentially it was a struggle of land against sea. On one side was the Spartan League, with Boeotia, Macedon (an unreliable ally) and Corinth as Sparta’s most important supporters; they held the Peloponnese and a belt of land separating Athens from the rest of Greece. Athens’ allies were scattered around the Aegean shore, in the Ionian cities and the islands, the area it had dominated since the days of the Delian League. Strategy was dictated by the means available. Sparta’s army, clearly, was best used to occupy Athenian territory and then exact submission. The Athenians could not match their enemies on land. But they had the better navy. This was in large measure the creation of a great Athenian statesman and patriot, the demagogue Pericles. On the fleet he based a strategy of abandoning the Athenian countryside to annual invasion by the Spartans – it was in any case never capable of feeding the population – and withdrawing the inhabitants to the city and its port, the Piraeus, to which it was linked by two walls some five miles long, 200 yards apart. There the Athenians could sit out the war, untroubled by bombardment or assault, which were beyond the capacities of Greek armies. Their fleet, still controlling the sea, would assure they were fed in war as in peace, by imported corn, so that blockade would not be effective.

Things did not work as well as this, because of plague within the city and the absence of leadership after Pericles’s death in 429

BC

, but the basic sterility of the first ten years of the war rests on this strategical deadlock. It brought peace for a time in 421

BC

, but not a lasting one. Athenian frustrations found an outlet in the end in a scheme to carry the war further afield.

In Sicily lay the rich city of Syracuse, the most important colony of

Corinth, herself the greatest of Athens’ commercial rivals. To seize Syracuse would deeply wound an enemy, finish off a major grain-supplier to the Peloponnese, and provide immense booty. With this wealth Athens could hope to build and man a yet bigger fleet and thus achieve a final and unquestioned supremacy in the Greek world – perhaps the mastery of the Phoenician city of Carthage and a western Mediterranean hegemony, too. The result was the disastrous Sicilian Expedition of 415–413

BC

. It was decisive, but as a death-blow to the ambitions of Athens. Half her army and all her fleet were lost; a period of political upheaval and disunion began at home. Finally, the defeat once more crystallized the alliance of Athens’ enemies.

The Spartans now sought and obtained Persian help in return for a secret undertaking that the Greek cities of mainland Asia should again become vassals of Persia (as they had been before the Persian War). This enabled them to raise the fleet which could help the Athenian subject cities who wanted to shake off its imperial control. Military and naval defeat undermined morale in Athens. In 411

BC

an unsuccessful revolution replaced the democratic regime briefly with an oligarchy. Then there were more disasters, the capture of the Athenian fleet and, finally, blockade. This time starvation was decisive. In 404

BC

Athens made peace and her fortifications were slighted.

Formally the story ends here, for what followed was implicit in the material and psychological damage the leading states of Greece had done to one another in these bitter years. There followed a brief Spartan hegemony during which she attempted to prevent the Persians cashing the promissory note on the Greek Asian cities, but this had to be conceded after a war which brought a revival of Athenian naval power and the rebuilding of the Long Walls. In the end, Sparta and Persia had a common interest in preventing a renaissance of Athenian power and made peace in 387

BC

. The settlement included a joint guarantee of all the other Greek cities except those of Asia. Ironically, the Spartans soon became as hated as the Athenians had been. Thebes took the leadership of their enemies. At Leuctra, in 371

BC

, to the astonishment of the rest of Greece, the Spartan army was defeated. It marked a psychological and military epoch in something of the same way as the battle of Jena in Prussian history over 2000 years later. The practical consequences made this clear, too; a new confederation was set up in the Peloponnese as a counterweight to Sparta on her very doorstep and the foundation of a revived Messenia in 369

BC

was another blow. The new confederation was a fresh sign that the day of the city-state was passing. The next half-century would see it all but disappear, but 369

BC

is far enough to take the story for the moment.

Such events would be tragic in the history of any country. The passage from the glorious days of the struggle against Persia to the Persians’ almost effortless recouping of their losses, thanks to Greek divisions, is a rounded drama which must always grip the imagination. Another reason why such intense interest has been given to it is that it was the subject-matter of an immortal book, Thucydides’

History of the Peloponnesian War

, the first work of contemporary as well as of scientific history. But the fundamental explanation why these few years should fascinate us when greater struggles do not is because we feel that at the heart of the jumble of battles, intrigues, disasters and glory still lies an intriguing and insoluble puzzle: was there a squandering of real opportunities after Mycale, or was this long anti-climax simply a dissipation of an illusion, circumstances having for a moment seemed to promise more than in fact was possible?

The war years have another startling aspect, too. During them there came to fruition the greatest achievement in civilization the world had ever seen. Political and military events then shaped that achievement in certain directions and in the end limited it and determined what should continue to the future. This is why the century or so of this small country’s history, whose central decades are those of the war, is worth as much attention as the millennial empires of antiquity.

At the outset we should recall how narrow a plinth supported Greek civilization. There were many Greek states, certainly, and they were scattered over a large expanse of the Aegean, but even if Macedonia and Crete were included, the land-surface of Greece would fit comfortably into England without Wales or Scotland – and of it only about one-fifth could be cultivated. Of the states, most were tiny, containing not more than 20,000 souls at most; the biggest might have had 300,000. Within them only a small élite took part in civic life and the enjoyment of what we now think of as Greek civilization.

The other thing to be clear about at the outset is the essence of that civilization. The Greeks were far from underrating comfort and the pleasures of the senses. The physical heritage they left behind set the canons of beauty in many of the arts for 2000 years. Yet in the end the Greeks are remembered as poets and philosophers; it is an achievement of the mind that constitutes their major claim on our attention. This has been recognized implicitly in the idea of classical Greece, a creation of later ages rather than of the Greeks themselves. Certainly some Greeks of the fifth and fourth centuries

BC

saw themselves as the bearers of a culture which was superior to any other available, but the force of the classical ideal lies in its being a view from a later age, one which looked back to Greece and found there standards by which to assess itself. Later generations saw these

standards above all in the fifth century, in the years following victory over the Persians, but there is a certain distortion in this. There is also an Athenian bias in such a view, for the fifth century was the apogee of Athenian cultural success. Nevertheless, to distinguish classical Greece from what went before – usually named ‘archaic’ or ‘pre-classical’ – makes sense. The fifth century has an objective unity because it saw a special heightening and intensification of Greek civilization, even if that civilization was ineradicably tied to the past, ran on into the future and spilled out over all the Greek world.

That civilization was rooted still in relatively simple economic patterns; essentially, they were those of the preceding age. No great revolution had altered it since the introduction of money and for three centuries or so there were only gradual or specific changes in the direction or materials of Greek trade. Some markets opened, some closed and the technical arrangements grew slightly more elaborate as the years went by, but that was all. And trade between countries and cities was the most advanced economic sector. Below this level, the Greek economy was still nothing like as complicated as would now be taken for granted. Barter, for example, persisted for everyday purposes well into the era of coinage. It also speaks for relatively simple markets, with only limited demands made on them by the consumer. The scale of manufacture, too, was small. It has been suggested that at the height of the craze for the best Athenian pottery not more than 150 craftsmen were at work making and painting it. We are not dealing with a world of factories; most craftsmen and traders probably worked as individuals with a few employees and slaves. Even great building projects, such as the embellishment of Athens, reveal subcontracting to small groups of workers. The only exception may have been in mining, where the silver mines of Laurium in Attica might have been worked by thousands of slaves, though the arrangements under which this was done – the mines belonged to the state and were in some way sublet – remain obscure. The heart of the economy almost everywhere was subsistence agriculture. In spite of the specialized demand and production of an Athens or a Miletus (which had something of a name as a producer of woollens) the typical community depended on the production by small farmers of grain, olives, vines and timber for the home market.

Such men were the typical Greeks. Some were rich, most of them were probably poor by modern standards, but even now the Mediterranean climate makes a relatively low income more tolerable than it would be elsewhere. Commerce on any scale, and other kinds of entrepreneurial activity, were likely to be mainly in the hands of metics. They might have considerable social standing and were often rich men, but, for example in Athens, they could not acquire land without special permission, though they were liable for military service (which gives us a little information about their numbers, for at the beginning of the Peloponnesian War there were some 3000 who could afford the arms and armour needed to serve as hoplite infantry). The other male inhabitants of the city-state who were not citizens were either freemen or slaves.

Women, too, were excluded from citizenship, though it is hazardous to generalize any further about their legal rights. In Athens, for example, they could neither inherit nor own property, though both were possible in Sparta, nor could they undertake a business transaction if more than the value of a bushel of grain was involved. Divorce at the suit of the wife was, it is true, available to Athenian women, but it seems to have been rare and was probably practically much harder to obtain than it was by men, who seem to have been able to get rid of wives fairly easily. Literary evidence suggests that wives other than those of rich men lived, for the most part, the lives of drudges. The social assumptions that governed all women’s behaviour were very restrictive; even women of the upper classes stayed at home in seclusion for most of the time. If they ventured out, they had to be accompanied; to be seen at a banquet put their respectability in

question. Entertainers and courtesans were the only women who could normally expect a public life; they could enjoy a certain celebrity, but a respectable woman could not. Significantly, in classical Greece girls were thought unworthy of education. Such attitudes suggest the primitive atmosphere of the society out of which they grew, one very different from, say, Minoan Crete among its predecessors, or later Rome.