The New Penguin History of the World (33 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

This civilization also varied in time. It showed greater powers of evolution than any of its predecessors. Even when they had undergone important political changes their institutions remained fundamentally intact, while Mediterranean civilization displays a huge variety of transient political forms and experiments. In religion and ideology, whereas other traditions tended to develop without violent changes or breaks, so that civilization and religion were virtually coterminous, the one living and dying with the other, Mediterranean civilization begins in a native paganism and ends by succumbing to an exotic import, Christianity, a revolutionized Judaism which was to be the first global religion. This was a huge change and it transformed this civilization’s possibilities of influencing the future.

Of all the forces making for its crystallization, the most fundamental was the setting itself, the Mediterranean basin. It was both a collecting area and a source; currents flowed easily into it from the lands of the old civilizations and from this central reservoir they also flowed back to where they came from and northwards into the barbarian lands. Though it is large and contains a variety of peoples, this basin has well-defined general characteristics. Most of its coasts are narrow plains behind which quickly

rise fairly steep and enclosing mountain ranges, broken by a few important river valleys. Those who lived on the coasts tended to look along them and outward across the sea, rather than behind them to their hinterland. This, combined with a climate they all shared, made the spreading of ideas and techniques within the Mediterranean natural for enterprising peoples.

The Romans, with reason, named the Mediterranean

Mare Magnum

, the Great Sea. It was the outstanding geographical fact of their world, the centre of classical maps. Its surface was a great uniting force for those who knew how to use it, and by 500

BC

maritime technology was advanced enough to make this possible except in winter. Prevailing winds and currents determined the exact routes of ships whose only power was provided by sails or oars, but any part of the Mediterranean was accessible by water from any other. The upshot was a littoral civilization, with a few languages spoken widely within it. It had specialized trading centres, for exchanges of materials were easy by sea, but the economy rested firmly on the growing of wheat and barley, olives and vines, mainly for local consumption. The metals increasingly needed by this economy could be brought in from outside. The deserts to the south were held at bay further from the coast and for perhaps thousands of years North Africa was richer than it now is, more heavily wooded, better watered, and more fertile. The same sort of civilization therefore tended to appear all around the Mediterranean. Such a difference between Africa and Europe as we take for granted did not exist until after

AD

500.

The outward-looking peoples of this littoral civilization created a new world. The great valley civilizations had not colonized, they had conquered. Their peoples looked inwards to the satisfaction of limited aims under local despots. Many later societies, even within the classical world, were to do the same, but there is a discernible change of tempo and potential from the start, and eventually Greeks and Romans grew corn in Russia, worked tin from Cornwall, built roads into the Balkans and enjoyed spices from India and silk from China.

About this world we know a great deal, partly because it left behind a huge archaeological and monumental legacy. Much more important, though, is the new richness of written material. With this, we enter the era of full literacy. Among other things, we confront the first true works of history; important as were to be the great folk records of the Jews, the narrations of a cosmic drama built about the pilgrimage of one people through time, they are not critical history. In any case, they, too, reach us through the classical Mediterranean world. Without Christianity, their influence would have been limited to Israel; through it, the myths they presented and the possibilities of meaning they offered were to be injected

into a world with 400 years of what we can recognize as critical writing of history already behind it. Yet the work of ancient historians, important as it is, is only a tiny part of the record. Soon after 500

BC

, we are in the presence of the first complete great literature, ranging from drama to epic, lyric hymn, history and epigram, though what is left of it is only a small part – seven out of more than a hundred plays by its greatest tragedian, for example. Nevertheless, it enables us to enter the mind of a civilization as we can enter that of none earlier.

Even for Greece, of course, the source of this literature, and

a fortiori

for other and more remote parts of the classical world, the written record is not enough on its own. The archaeology is indispensable, but it is all the more informative because literary sources are so much fuller than anything from the early past. The record they offer us is for the most part in Greek or Latin, the two languages which provided the intellectual currency of Mediterranean civilization. The persistence in English, the most widely used of languages today, of so many words drawn from them is by itself almost enough evidence to show this civilization’s importance to its successors (all seven nouns in the last sentence but one, for example, are based on Latin words). It was through writings in these languages that later men approached this civilization and in them they detected the qualities which made them speak of what they found simply as ‘

the

classical world’.

This is a perfectly proper usage, provided we remember that the men who coined it were heirs to the traditions they saw in it and stood, perhaps trapped, within its assumptions. Other traditions and civilizations, too, have had their ‘classical’ phases. What it means is that men see in some part of the past an age setting standards for later times. Many later Europeans were to be hypnotized by the power and glamour of classical Mediterranean civilization. Some men who lived in it, too, thought that they, their culture and times were exceptional, though not always for reasons we should now find convincing. Yet it

was

exceptional; vigorous and restless, it provided standards and ideals, as well as technology and institutions, on which huge futures were to be built. In essence, the unity later discerned by those who admired the Mediterranean heritage was a mental one.

Inevitably, there was to be much anachronistic falsification in some of the later efforts to study and utilize the classical ideal, and much romanticization of a lost age, too. Yet even when this is discounted, and when the classical past has undergone the sceptical scrutiny of scholars, there remains a big indissoluble residue of intellectual achievement which somehow places it on our side of a mental boundary, while the great empires

of Asia lie beyond it. With whatever difficulty and possibility of misconstruction, the mind of the classical age is recognizable and comprehensible in a way perhaps nothing earlier can be. ‘This’, it has been well said, ‘is a world whose air we can breathe.’

The role of the Greeks was pre-eminent in making this world and with them its story must begin. They contributed more than any other single people to its dynamism and to its mythical and inspirational legacy. The Greek search for excellence defined for later nations what excellence was and their achievement remains difficult to exaggerate. It is the core of the process which made classical Mediterranean civilization.

2

The Greeks

In the second half of the eighth century

BC

, the clouds which had hidden the Aegean since the end of the Bronze Age begin to part a little. Processes and sometimes events become somewhat more discernible. There is even a date or two, one of which is important in the history of a civilization’s self-consciousness: in 776

BC

, according to later Greek historians, the first Olympian games were held. After a few centuries the Greeks would count from this year as we count from the birth of Christ.

The people who gathered for that and later festivals of the same sort recognized by doing so that they shared a culture. Its basis was a common language; Dorians, Ionians, Aeolians all spoke Greek. What is more they had done so for a long time; the language was now to acquire the definition which comes from being written down, an enormously important development, making possible, for example, the recording of the traditional oral poetry, which was said to be the work of Homer. Our first surviving inscription in Greek characters is on a jug of about 750

BC

. It shows how much the renewal of Aegean civilization owed to Asia. The inscription is written in an adaptation of Phoenician script; Greeks were illiterate until their traders brought home this alphabet. It seems to have been used first in the Peloponnese, Crete and Rhodes; possibly these were the first areas to benefit from the renewal of intercourse with Asia after the Dark Ages. The process is mysterious and can probably never be recovered, but somehow the catalyst which precipitated Greek civilization was contact with the East.

Who were the Greek-speakers who attended the first Olympiad? Though it is the name by which they and their descendants are still known, they were not called Greeks; that name was only given them centuries later by the Romans. The word they would have used was the one we render in English as ‘Hellenes’. First used to distinguish invaders of the Greek peninsula from the earlier inhabitants, it became one applied to all the Greek-speaking peoples of the Aegean. This was the new conception and the new name emerging from the Dark Ages and there is more than a verbal

significance to it. It expressed a consciousness of a new entity, one still emerging and one whose exact meaning would always remain uncertain. Some of the Greek-speakers had in the eighth century already long been settled and their roots were lost in the turmoil of the Bronze Age invasions. Some were much more recent arrivals. None came as Greeks; they became Greeks by being there, all around the Aegean. Language identified them and wove new ties between them. Together with a shared heritage of religion and myth, it was the most important constituent of being Greek, always and supremely a matter of common culture.

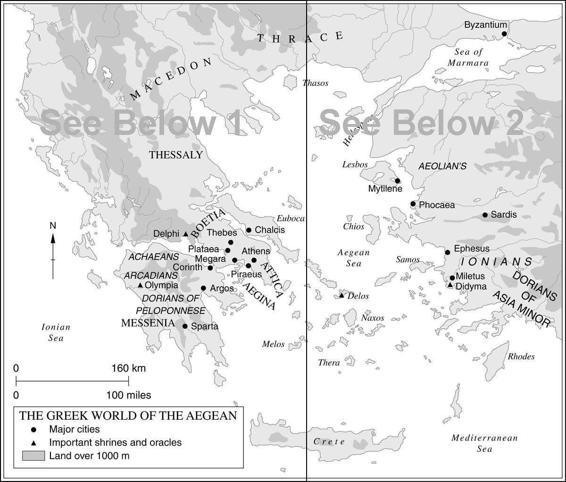

Yet such ties were never politically effective. They were unlikely to make for unity because of the size and shape of the theatre of Greek history, which was not what we now call Greece, but was, rather, the whole Aegean. The wide spread of Minoan and Mycenaean influences in earlier civilized times had foreshadowed this, for between the scores of its islands and the shores which closed about them it was easy to voyage during much of the year. The explanation of the appearance of Greek civilization at all may well be largely a matter of this geography. The past certainly counted for something, too, but Minoan Crete and Mycenae probably left less to Greece than Anglo-Saxon England left to a later Great Britain. The setting was more important than history for it made possible a cluster of economically viable communities using the same language and easily accessible not only to one another but to older centres of civilization in the Near East. Like the old river valleys – but for different reasons – the Aegean was a propitious place for civilization-making.

Much of the Aegean was settled by Greeks as a consequence of limitations and opportunities that they found on the mainland. Only in very small patches did its land and climate combine to offer the chance of agricultural plenty. For the most part, cultivation was confined to narrow strips of alluvial plain, which had to be dry-farmed, framed by rocky or wooded hills; minerals were rare, there was no tin, copper or iron. A few valleys ran direct to the sea and communication between them was usually difficult. All this inclined the inhabitants of Attica and the Peloponnese to look outwards to the sea, on the surface of which movement was much easier than on land. None of them, after all, lived more than forty miles from it.

This predisposition was intensified as early as the tenth century by a growth of population which brought greater pressure on available land. Ultimately this led to a great age of colonization; by the end of it, in the sixth century, the Greek world stretched far beyond the Aegean, from the Black Sea in the east to the Balearics, France and Sicily in the west and Libya in the south. But this was the result of centuries during which forces other than population pressure had also been at work. While Thrace was colonized by agriculturalists looking for land, other Greeks settled in the Levant or south Italy in order to trade, whether for the wealth it would bring or for the access it offered to the metals they needed and could not find in Greece. Some Black Sea Greek cities seem to be where they are because of trade, some because of their farming potential. Nor were traders and farmers the only agents diffusing Greek ways and teaching Greece about the outside world. The historical records of other countries show us that there was a supply of Greek mercenaries available from the sixth century (when they fought for the Egyptians against the Assyrians) onwards. All these facts were to have important social and political repercussions on the Greek homeland.