The New Penguin History of the World (30 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Perhaps, therefore, it is climate which drives us back upon Egypt as the beginning of African history. Yet Egypt exercised little creative influence beyond the limits of the Nile valley. Though there were contacts with other cultures, it is not easy to penetrate them. Presumably the Libyans of Egyptian records were the sort of people who are shown with their chariots in the Sahara cave-paintings, but we do not certainly know. When the Greek historian Herodotus came to write about Africa in the fifth century

BC

, he found little to say about what went on outside Egypt. His Africa (which he called Libya) was a land defined by the Nile, which he took to run south, roughly parallel to the Red Sea, and then to swing westwards. South of the Nile there lay for him in the east the Ethiopians, in the west a land of deserts, without inhabitants. He could obtain no information about it, though a travellers’ tale spoke of a dwarfish people who were sorcerers. Given his sources, this was topographically by no means an unintelligent construction, but Herodotus had grasped only a small part of the ethnic truth. The Ethiopians, like the old inhabitants of upper Egypt, were members of the Hamitic peoples who make up one of three racial groups in Africa at the end of the Stone Age later distinguished by anthropologists. The other two were the ancestors of the modern Bushmen (now sometimes called the ‘San’ people), inhabiting, roughly, the open areas running from the Sahara south to the Cape, and the Negroid group, eventually dominant in the central forests and West Africa. (Opinion is divided about the origin and distinctiveness of a fourth group, the Pygmies.) To judge by the stone tools, cultures associated with Hamitic or proto-Hamitic peoples seem to have been the most advanced in Africa before the coming of farming. This was, except in Egypt, a slow evolution and in Africa the hunting and gathering cultures of prehistory have coexisted with agriculture right down to modern times.

The same growth which occurred elsewhere when food began to be produced in quantity soon changed African population patterns, first by permitting the dense settlements of the Nile valley, which were the preliminary to Egyptian civilization, then by building up the Negroid population south of the Sahara, along the grasslands separating desert and equatorial forest in the second and first millennia

BC

. This seems to reflect a spread of agriculture southwards from the north. It also reflects the discovery of nutritious crops better suited to tropical conditions and other soils than the wheat and barley which flourished in the Nile valley. These were the millets and rice of the savannahs. The forest areas could not be exploited

until the coming of other plants suitable to them from South-East Asia and eventually America. None of this happened before the birth of Christ. Thus was established one of the major characteristics of African history, a divergence of cultural trends within the continent.

By that time, iron had come to Africa and it had already produced the first exploitation of African ores. This occurred in the first independent African state other than Egypt of which we have information, the kingdom of Kush, high up the Nile, in the region of Khartoum. This had originally been the extreme frontier zone of Egyptian activity. After Nubia had been absorbed, the Sudanese principality which existed to its south was garrisoned by the Egyptians, but in about 1000

BC

it emerged as an independent kingdom, showing itself deeply marked by Egyptian civilization. Probably its inhabitants were Hamitic people and its capital was at Napata, just below the Fourth Cataract. By 730

BC

Kush was strong enough to conquer Egypt and five of its kings ruled as the pharaohs known to history as the Twenty-Fifth or ‘Ethiopian’ Dynasty. None the less, they could not arrest the Egyptian decline. When the Assyrians fell on Egypt, the Kushite dynasty ended. Though Egyptian civilization continued in the kingdom of Kush, a pharaoh of the next dynasty invaded it in the early sixth century

BC

. After this, the Kushites, too, began to push their frontiers further to the south and in so doing their kingdom underwent two important changes. It became more Negroid, its language and literature reflecting a weakening of Egyptian trends, and it extended its reach over new territories which contained both iron ore and the fuel needed to smelt it. The technique of smelting had been learnt from the Assyrians. The new Kushite capital at Meroe became the metallurgical centre of Africa. Iron weapons gave the Kushites the advantages over their neighbours which northern peoples had enjoyed in the past over Egypt, and iron tools extended the area which could be cultivated. On this basis was to rest some 300 years of prosperity and civilization in the Sudan, though later than the age we are now considering.

It is clear that the history of man in the Americas is much shorter than that in Africa or, indeed, than anywhere else. About 20,000 years ago, after Mongoloid peoples had crossed into North America from Asia, they filtered slowly southwards for thousands of years. Cave-dwellers have been traced in the Peruvian Andes as many as 15,000 years ago. The Americas contain very varied climates and environments; it is scarcely surprising, therefore, that archaeological evidence shows that they threw up almost equally varied patterns of life, based on different opportunities for hunting, food-gathering and fishing. What they learnt from one another is probably undiscoverable. What is indisputable is that some of these

cultures arrived at the invention of agriculture independently of the Old World.

Disagreement is still possible about when precisely this happened because, paradoxically, a great deal is known about the early cultivation of plants at a time when the scale on which this took place cannot reasonably be called agriculture. It is, nevertheless, a change which comes later than in the Fertile Crescent. Maize began to be cultivated in Mexico in about 2700

BC

, but had been improved by 2000

BC

in Meso-America into something like the plant we know today. This is the sort of change which made possible the establishment of large settled communities. Further south, potatoes and manioc (another starchy root vegetable) also begin to appear at about this time and a little later there are signs that maize has spread southwards from Mexico. Everywhere, though, change is gradual; to think of an ‘agricultural revolution’ as a sudden event is even less appropriate in the Americas than in the Near East. Yet it had an impact which was truly revolutionary not only in time, but beyond America itself. The sweet potato, a native of Mexico and Central America, was to spread across the Pacific to sustain island farming communities centuries before the European galleons of the colonial era took it to Africa, the Indian Ocean and the Philippines.

Farming, villages, weaving and pottery all appear in Central America before the second millennium

BC

and towards the end of it come the first stirrings of the culture which produced the first recognized American civilization, that of the Olmecs of the eastern Mexican coast. It was focused, it seems, on important ceremonial sites with large earth pyramids. At these sites have been found colossal monumental sculpture and fine carvings of figures in jade. The style of this work is highly individual. It concentrates on human and jaguar-like images, sometimes fusing them. For several centuries after 800

BC

it seems to have prevailed right across Central America as far south as what is now El Salvador. It appears apparently without antecedents or warning in a swampy, forested region which makes it hard to explain in economic terms except that maize could be harvested four times a year where there was open land in tropics supplying reliable rainfall and warmth all year. Yet we do not know much else which helps to explain why civilization, which elsewhere required the relative plenty of the great river valleys, should in America have sprung from such unpromising soil.

Olmec civilization transmitted something to the future, for the gods of the later Aztecs were to be descendants of those of the Olmecs. It may also be that the early hieroglyphic systems of Central America originate in Olmec times, though the first survivals of the characters of these systems follow only a century or so after the disappearance of Olmec culture in about 400

BC

. Again, we do not know why or how this happened. Much further south, in Peru, a culture called Chavin (after a great ceremonial site) also appeared and survived a little later than Olmec civilization to the north. It, too, had a high level of skill in working stone and spread vigorously only to dry up mysteriously.

What should be thought of these early lunges in the direction of civilization is very hard to see. Whatever their significance for the future, they are millennia behind the appearance of civilization elsewhere, whatever the cause of that may be. When the Spanish landed in the New World nearly 2000 years after the disappearance of Olmec culture they would still find most of its inhabitants working with stone tools. They would also find complicated societies (and the relics of others) which had achieved prodigies of building and organization far outrunning, for example, anything Africa could offer after the decline of ancient Egypt. All that is clear is that there are no unbreakable sequences in these matters.

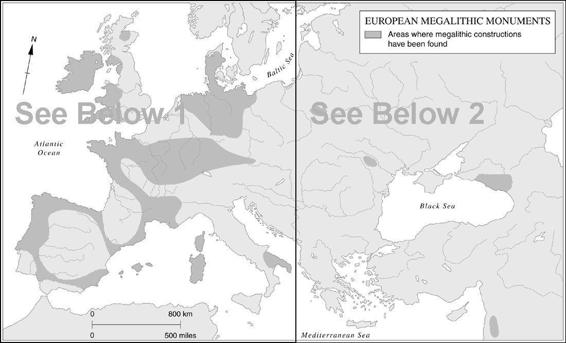

The only other area where a startlingly high level of achievement in stone-working was reached was western Europe. This has led enthusiasts to claim it as another seat of early ‘civilization’, almost as if its inhabitants were some sort of depressed class needing historical rehabilitation. Europe has already been touched upon as a supplier of metals to the ancient Near East. Yet, though much that we now find interesting was happening there in prehistoric times, it does not provide a very impressive or striking story. In the history of the world, prehistoric Europe has little except illustrative importance. To the great civilizations which rose and fell in the river valleys

of the Near East, Europe was largely an irrelevance. It sometimes received the impress of the outside world but contributed only marginally and fitfully to the process of historic change. A parallel might be Africa at a later date, interesting for its own sake, but not for any special and positive contribution to world history. It was to be a very long time before men would even be able to conceive that there existed a geographical, let alone a cultural, unity corresponding to the later idea of Europe. To the ancient world, the northern lands where the barbarians came from before they appeared in Thrace were irrelevant (and most of them probably came from further east anyway). The north-western hinterland was only important because it occasionally disgorged commodities wanted in Asia and the Aegean.

There is not much to say, therefore, about prehistoric Europe, but in order to get a correct perspective, one more point should be made. Two Europes must be distinguished. One is that of the Mediterranean coasts and their peoples. Its rough boundary is the line which delimits the cultivation of the olive. South of this line, literate, urban civilization comes fairly quickly once we are into the Iron Age, and apparently after direct contact with more advanced areas. By 800

BC

the coasts of the western Mediterranean were already beginning to experience fairly continuous intercourse with the East. The Europe north and west of this line is a different matter. In this area literacy was never achieved in antiquity, but was imposed much later by conquerors. It long resisted cultural influences from the south and east – or at least did not offer a favourable reception to them – and it is for 2000 years important not for its own sake but because of its relationship to other areas. Its role was not entirely passive: the movements of its peoples, its natural resources and skills all at times impinged marginally on events elsewhere. But in 1000

BC

– to take an arbitrary date – or even at the beginning of the Christian era, Europe has little of its own to offer the world except its minerals, and nothing which represents cultural achievement on the scale reached by the Near East, India or China. Europe’s age was still to come; hers would be the last great civilization to appear.