The New Penguin History of the World (27 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Ancient writers recognized the importance of this revolutionary social change and legends identified a specific inventor of agriculture, yet very little can be inferred confidently or clearly about social organization at this stage. Perhaps because of this there has been a persistent tendency among Chinese to idealize it. Long after private property had become widespread it was assumed that ‘under heaven every spot is the sovereign’s ground’ and this may reflect early ideas that all land belonged to the community as a whole. Chinese Marxists later upheld this tradition, discerning in the archaeological evidence a golden age of primitive Communism preceding a descent into slave and feudal society. Argument is unlikely to convince those interested in the question one way or the other. Ground seems to be firmer in attributing to these times the appearance of a clan structure and totems, with prohibitions on marriage within the clan. Kinship in this form is almost the first institution which can be seen to have survived to be important in historical times. The evidence of the pottery, too, suggests

some new complexity in social roles. Already things were being made which cannot have been intended for the rough and tumble of everyday use; a stratified society seems to be emerging before we reach the historical era.

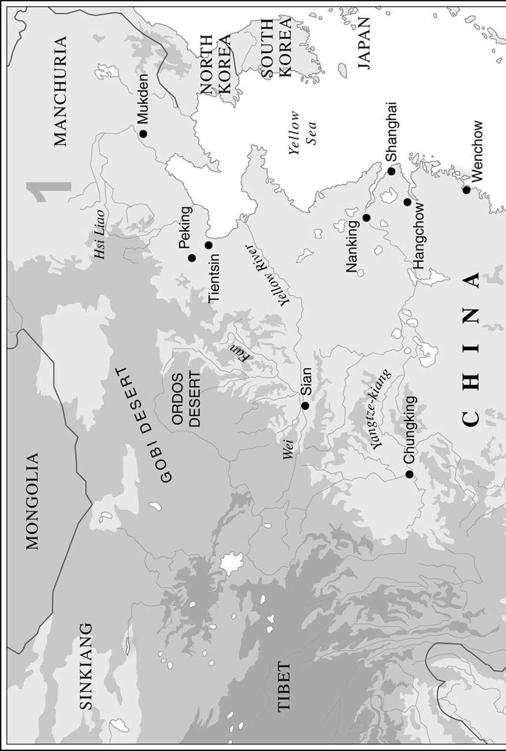

One material sign of a future China already obvious at this stage is the widespread use of millet, a grain well adapted to the sometimes arid farming of the north. It was to be the basic staple of Chinese diet until about a thousand years ago and sustained a society which in due course arrived at literacy, at a great art of bronze-casting based on a difficult and advanced technology, at the means of making exquisite pottery far finer than anything made anywhere else in the world and, above all, at an ordered political and social system which identifies the first major age of Chinese history. But it must be remembered once more that the agriculture which made this possible was for a long time confined to north China and that many parts of this huge country only took up farming when historical times had already begun.

The narrative of early times is very hard to recover, but can be outlined with some confidence. It has been agreed that the story of civilization in China begins under rulers from a people called the Shang, the first name with independent evidence to support it in the traditional list of dynasties which was for a long time the basis of Chinese chronology. From the late eighth century

BC

we have better dates, but we still have no chronology for early Chinese history as well founded as, say, that of Egypt. It is more certain that somewhere about 1700

BC

(and a century each way is an acceptable margin of approximation) a tribe called the Shang, which enjoyed the military advantage of the chariot, imposed itself on its neighbours over a sizeable stretch of the Yellow River valley. Eventually, the Shang domain was a matter of about 40,000 square miles in northern Honan: this made it somewhat smaller than modern England, though its cultural influences reached far beyond its periphery, as evidence from as far away as south China, Chinese Turkestan and the north-eastern coast shows.

Shang kings lived and died in some state; slaves and human sacrificial victims were buried with them in deep and lavish tombs. Their courts had archivists and scribes, for this was the first truly literate culture east of Mesopotamia. This is one reason for distinguishing between Shang civilization and Shang dynastic paramountcy; this people showed a cultural influence which certainly extended far beyond any area they could have dominated politically. The political arrangements of the Shang domains themselves seem to have depended on the uniting of landholding with obligations to a king; the warrior landlords who were the key figures were the leading members of aristocratic lineages with semi-mythical origins. Yet Shang government was advanced enough to use scribes and had a standardized currency. What it could do when at full stretch is shown in its ability to mobilize large amounts of labour for the building of fortifications and cities.

Shang China succumbed in the end to another tribe from the west of the valley, the Chou. A probable date is between 1150 and 1120

BC

. Under the Chou, many of the already elaborate governmental and social structures

inherited from the Shang were preserved and further refined. Burial rites, bronze-working techniques and decorative art also survived in hardly altered forms. The great work of the Chou period was the consolidation and diffusion of this heritage. In it can be discerned the hardening of the institutions of a future Imperial China which would last 2000 years.

The Chou thought of themselves as surrounded by barbarian peoples, waiting for the benevolent effects of Chou tranquillization (an idea, it may be remarked, which still underlay the persistent refusal of Chinese officials 2000 years later to regard diplomatic missions from Europe as anything but respectful bearers of tribute). Chou supremacy in fact rested on war, but from it flowed great cultural consequences. As under the Shang, there was no truly unitary state and Chou government represented a change of degree rather than kind. It was usually a matter of a group of notables and vassals, some more dependent on the dynasty than others, offering in good times at least a formal acknowledgement of its supremacy and all increasingly sharing in a common culture. Political China (if it is reasonable to use such a term) rested upon big estates which had sufficient cohesion to have powers of long survival and in this process their original lords turned into rulers who could be called kings, served by elementary bureaucracies.

This system collapsed from about 700

BC

, when a barbarian incursion drove the Chou from their ancestral centre to a new home further east, in Honan. The dynasty did not end until 256

BC

, but the next distinguishable epoch dates from 403 to 221

BC

and is significantly known as the Period of the Warring States. In it, historical selection by conflict grew fierce. Big fish ate little fish until one only was left and all the lands of the Chinese were for the first time ruled by one great empire, the Ch’in, from which the country was to get its name. This is matter for discussion elsewhere; here it is enough to register an epoch in Chinese history.

Reading about these events in the traditional Chinese historical accounts can produce a slight feeling of beating the air, and historians who are not experts in Chinese studies may be forgiven if they cannot trace over this period of some 1500 years or so any helpful narrative thread in the dimly discernible struggles of kings and over-mighty subjects. Indeed, scholars have not yet provided one. Nevertheless, two basic processes were going on for most of this time, which were very important for the future and which give the period some unity, though their detail is elusive. The first of these was a continuing diffusion of culture outwards from the Yellow River basin.

To begin with, Chinese civilization was a matter of tiny islands in a sea of barbarism. Yet by 500

BC

it was the common possession of scores,

perhaps hundreds, of what have been termed ‘states’ scattered across the north, and it had also been carried into the Yangtze valley. This had long been a swampy, heavily forested region, very different from the north and inhabited by far more primitive peoples. Chou influence – in part thanks to military expansion – irradiated this area and helped to produce the first major culture and state of the Yangtze valley, the Ch’u civilization. Although owing much to the Chou, it had many distinctive linguistic, calligraphic, artistic and religious traits of its own. By the end of the Period of Warring States we have reached the point at which the stage of Chinese history is about to be much enlarged.

The second of these fundamental and continuing processes under both Shang and Chou was the establishment of landmarks in institutions which were to survive until modern times. Among them was a fundamental division of Chinese society into a landowning nobility and the common people. Most of these were peasants, making up the vast majority of the population and paying for all that China produced in the way of civilization and state power. What little we know of their countless lives can be quickly said; even less can be discovered than about the anonymous masses of toilers at the base of every other ancient civilization. There is one good physical reason for this: the life of the Chinese peasant was an alternation between his mud hovel in the winter and an encampment where he lived during the summer months to guard and tend his growing crops. Neither has left much trace. For the rest, he appears sunk in the anonymity of his community (he does not belong to a clan), tied to the soil, occasionally taken from it to carry out other duties and to serve his lord in war or hunting. His depressed state is expressed by the classification of Chinese communist historiography which lumped Shang and Chou together as ‘Slavery Society’ preceding the ‘Feudal Society’ which comes next.

Though Chinese society was to grow much more complex by the end of the Warring States Period, this distinction of common people from the nobly born remained. There were important practical consequences: the nobility, for example, were not subject to punishments – such as mutilation – inflicted on the commoner; it was a survival of this in later times that the gentry were exempt from the beatings which might be visited on the commoner (though, of course, they might suffer appropriate and even dire punishment for very serious crimes). The nobility long enjoyed a virtual monopoly of wealth, too, which outlasted its earlier monopoly of metal weapons. None the less, these were not the crucial distinctions of status, which lay elsewhere, in the nobleman’s special religious standing through a monopoly of certain ritual practices. Only noblemen could share in the cults which were the heart of the Chinese notion of kinship. Only the

nobleman belonged to a family – which meant that he had ancestors. Reverence for ancestors and propitiation of their spirits had existed before the Shang, though it does not seem that in early times many ancestors were thought likely to survive into the spirit world. Possibly the only ones lucky enough to do so would be the spirits of particularly important persons; the most likely, of course, were the rulers themselves, whose ultimate origin, it was claimed, was itself godly.

The family emerged as a legal refinement and sub-division of the clan, and the Chou period was the most important one in its clarification. There were about a hundred clans, within each of which marriage was forbidden. Each was supposed to be founded by a hero or a god. The patriarchal heads of the clan’s families and houses exercised special authority over its members and were all qualified to carry out its rituals and thus influence spirits to act as intermediaries with the powers which controlled the universe on the clan’s behalf. These practices came to identify persons entitled to possess land or hold office. The clan offered a sort of democracy of opportunity at this level: any of its members could be appointed to the highest place in it, for they were all qualified by the essential virtue of a descent whose origins were godlike. In this sense, a king was only

primus inter pares

, a patrician outstanding among all patricians.