The New Penguin History of the World (24 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

The glory of the empire came to a focus in the cult of Marduk, which was now at its zenith. At a great New Year festival held each year all the Mesopotamian gods – the idols and statues of provincial shrines – came down the rivers and canals to take counsel with Marduk at his temple and acknowledge his supremacy. Borne down a processional way three-quarters

of a mile long (which was, we are told, probably the most magnificent street of antiquity) or landed from the Euphrates nearer to the temple, they were taken into the presence of a statue of the god which, Herodotus reported two centuries later, was made of two and a quarter tons of gold. No doubt he exaggerated, but it was indisputably magnificent. The destinies of the whole world, whose centre was this temple, were then debated by the gods and determined for another year. Thus theology reflected political reality. The re-enacting of the drama of creation was the endorsement of Marduk’s eternal authority, and this was an endorsement of the absolute monarchy of Babylon. The king had responsibility for assuring the order of the world and therefore the authority to do so.

It was the last flowering of the Mesopotamian tradition and was soon to end. More and more provinces were lost under Nebuchadnezzar’s successors. Then came an invasion in 539

BC

by new conquerors from the east, the Persians, led by the Achaemenids. The passage from worldly pomp and splendour to destruction had been swift. The book of Daniel telescopes it in a magnificent closing scene, Belshazzar’s feast. ‘In that night,’ we read, ‘was Belshazzar the king of the Chaldeans slain. And Darius the Median took the kingdom’ (Daniel 5: 30–31). Unfortunately, this account was only written 300 years later and it was not quite like that. Belshazzar was neither Nebuchadnezzar’s son nor his successor as the book of Daniel says, and the king who took Babylon was called Cyrus. None the less, the emphasis of the Jewish tradition has a dramatic and psychological truth. In so far as the story of antiquity has a turning-point, this is it. An independent Mesopotamian tradition going back to Sumer was over. We are at the edge of a new world. A Jewish poet summed it up exultantly in the book of Isaiah, where Cyrus appears as a deliverer to the Jews:

‘

Sit thou silent, and get thee into darkness, O daughter of the Chaldeans: for thou shalt no more be called, The lady of kingdoms.’

Isaiah 47: 5

5

The Beginnings of Civilization in Eastern Asia

From the beginnings to the most recent times the centre of gravity of world history has usually swung about between the Atlantic and Iran. Yet (also until the most recent times) what went on there had little direct impact elsewhere. Much of the life of other parts of the world long remained virtually impervious to the influence of its civilizations and two areas were especially resistant: India and China. By 1000

BC

civilizations had appeared in these countries which were, in spite of peripheral contacts, quite independent of the Near East. They were the foundations of splendid and enduring cultural traditions which were to outlive those of Mesopotamia and Egypt, and they would each enjoy a huge sphere of influence.

ANCIENT INDIA

Even now, ancient India is still visible and accessible to us in a very direct sense. At the beginning of the twentieth century, some Indian communities still lived as all our primeval ancestors must once have lived, by hunting and gathering. The bullock-cart and the potter’s wheel of many villages today are, as far as can be seen, much the same as those used 4000 years ago. A caste-system whose main lines were set by about 1000

BC

still regulates the lives of millions, and even of some Indian Christians and Moslems. Gods and goddesses whose cults can be traced to the Stone Age are still worshipped at village shrines.

In some ways, then, ancient India is with us still as is no other ancient civilization. Yet though such examples of the conservatism of Indian life are commonplace, the country contains many other things too. The hunter-gatherers of the early twentieth century were the contemporaries of other Indians used to travelling in railway trains. The diversity of Indian life is enormous, but wholly comprehensible given the size and variety of its setting. The sub-continent is, after all, about the size of Europe and is divided into regions clearly distinguished by climate, terrain and crops.

There are two great river valleys, the Indus and Ganges systems, in the north; between them lie desert and arid plains, and to the south the highlands of the Deccan, largely forested. When written history begins, India’s racial complexity, too, is already very great: scholars identify six main ethnic groups. Many others were to arrive later and make themselves at home in the Indian sub-continent and society, too. All this makes it hard to find a focus.

Yet Indian history has a unity in the fact of its enormous power to absorb and transform forces playing on it from the outside. This provides a thread to guide us through the patchy and uncertain illumination of its early stages which is provided by archaeology and texts long transmitted only by word of mouth. Its basis is to be found in another fact: India’s large measure of insulation from the outside world by geography. In spite of her size and variety, until the oceans began to be opened up in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries India had only to grapple with occasional, though often irresistible, incursions by alien peoples. To the north and north-west she was protected by some of the highest mountains in the world; to the east lay belts of jungle. The other two sides of the sub-continent’s great triangle opened out into the huge expanses of the Indian ocean. This natural definition not only channelled and restricted communication with the outside world, it also gave India a distinctive climate. Much of India does not lie in the tropics, but none the less that climate is tropical. The mountains keep away the icy winds of Central Asia; the long coasts open themselves to the rain-laden clouds which roll in from the oceans and cannot go beyond the northern ranges. The climatic clock is the annual monsoon, bringing the rain during the hottest months of the year. It is still the central prop of the agricultural economy.

Protected in some measure from external forces though she has always been before modern times, India’s north-western frontier is more open than her others to the outside world. Baluchistan and the frontier passes were the most important zones of encounter between India and other peoples right down to the seventeenth century

AD

; in civilized times even India’s contacts with China were first made by this roundabout route (though it is not quite as roundabout as Mercator’s familiar projection makes it appear). At times, this north-western region has fallen directly under foreign sway, which is suggestive when we consider the first Indian civilizations; we do not know much about the way in which they arose but we know that Sumer and Egypt antedated them. Mesopotamian records of Sargon I of Akkad report contacts with a ‘Meluhha’ which scholars have believed to be the Indus valley, the alluvial plains forming the first natural region encountered by the traveller once he has entered India. It was

there, in rich, heavily forested countryside, that the first Indian civilizations appeared at the time when, further west, the great movements of Indo-European peoples were beginning to act as the levers of history. There may have been more than one stimulus at work.

The evidence also shows that agriculture came later to India than to the Near East. It, too, can first be traced in the sub-continent in its north-west corner. There is archaeological evidence of farming in Baluchistan in about 6000

BC

. Three thousand years later, signs of settled life on the alluvial plains and parallels with other river-valley cultures begin to appear. Wheel-thrown pottery and copper implements begin to be found. All the signs are of a gradual build-up in intensity of agricultural settlements until true civilization appears as it did in Egypt and Sumer. But there is the possibility of direct Mesopotamian influence in the background and, finally, there is at least a reasonable inference that already India’s future was being shaped by the coming of new peoples from the north. At a very early date the complex racial composition of India’s population suggests this, though it would be rash to be assertive about it.

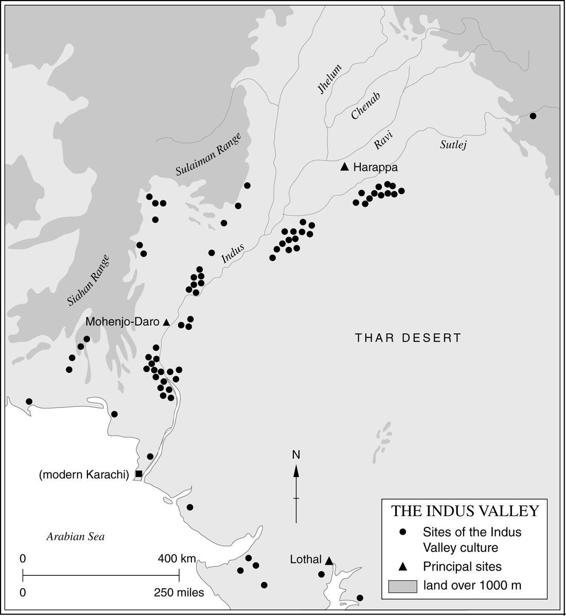

When at last indisputable evidence of civilized life is available, the change is startling. One scholar speaks of a cultural ‘explosion’. There may have been one crucial technological step, the invention of burnt brick (as opposed to the sun-baked mud brick of Mesopotamia) which made flood control possible in a flat plain lacking natural stone. Whatever the process, the outcome was a remarkable civilization which stretched over more than a quarter-million square miles of the Indus valley, an area greater than either the Sumerian or Egyptian.

Some have called Indus civilization ‘Harappan’, because one of its great sites is the city of Harappa on a tributary of the Indus. There is another such site at Mohenjo-Daro; three others are known. Together they reveal human beings highly organized and capable of carefully regulated collective works on a scale equalling those of Egypt and Mesopotamia. There were large granaries in the cities, and weights and measures seem to have been standardized over a large area. It is clear that a well-developed culture was established by 2600

BC

and lasted for something like 600 years with very little change, before declining in the second millennium

BC

.

The two cities which are its greatest monuments may have contained more than 30,000 people each. This says much for the agriculture which sustained them; the region was then far from being the arid zone it later became. Mohenjo-Daro and Harappa were between two and two and a half miles in circumference and the uniformity and complexity of their building speaks for a very high degree of administrative and organizational skill. They each had a citadel and a residential area; streets of houses were

laid out on rectangular grid plans and made of bricks of standardized sizes. Both the elaborate and effective drainage systems and the internal layout of the houses show a strong concern for bathing and cleanliness; in some streets of Harappa nearly every house has a bathroom. Perhaps it is not fanciful to see in this some of the first manifestations of what has become an enduring feature of Indian religion, the bathing and ritual ablutions still so important to Hindus.

These cities traded far afield and lived an economic life of some complexity. A great dockyard, connected by a mile-long canal to the sea at Lothal, 400 miles south of Mohenjo-Daro, suggests the importance of external exchanges which reached, through the Persian Gulf, as far north as Mesopotamia. In the Harappan cities themselves evidence survives of specialized craftsmen drawing their materials from a wide area and subsequently sending out again across its length and breadth the products of their skills. This civilization had cotton cloth (the first of which we have evidence), which was plentiful enough to wrap bales of goods for export whose cordage was sealed with seals found at Lothal. These seals are part of our evidence for Harappan literacy; a few inscriptions on fragments of pottery are all that supplements them and provides the first traces of Indian writing. The seals, of which about 2500 survive, provide some of our best clues to Harappan ideas. The pictographs on the seals run from right to left. Animals often appear on them and may represent six seasons into which the year was divided. Many ‘words’ on the seals remain unreadable, but it now seems at least likely that they are part of a language akin to the Dravidian tongues still used in southern India.

Ideas and techniques from the Indus spread throughout Sind and the Punjab, and down the west coast of Gujarat. The process took centuries and the picture revealed by archaeology (some sites are now submerged by the sea) is too confused for a consistent pattern to emerge. Where its influence did not reach – the Ganges valley, the other great silt-rich area where large populations could live, and the south-east – different cultural processes were at work, but they have left nothing so spectacular behind them. Some of India’s culture must derive from other sources; there are traces elsewhere of Chinese influence. But it is hard to be positive. Rice, for example, began to be grown in India in the Ganges valley; we simply do not know where it came from, but one possibility is China or South-East Asia, on whose coasts it was grown from about 3000

BC

. Two thousand years later, this crucial item in Indian diet was used over most of the north.

Nor do we know why the first Indian civilizations began to decline, though their passing can be roughly dated. The devastating floods of the Indus or uncontrollable alterations of its course may have wrecked the delicate balance of the agriculture on its banks. The forests may have been destroyed by tree-felling to provide fuel for the brick-kilns on which Harappan building depended. But perhaps there were also other agencies at work. Skeletons, possibly those of men killed where they fell, were found in the streets of Mohenjo-Daro. Harappan civilization seems to end in the Indus valley about 1750

BC

and this coincides strikingly with the irruption into Indian history of one of its great creative forces, invading ‘Aryans’, though scholars do not favour the idea that invaders destroyed the Indian valley cities. Perhaps the newcomers entered a land already devastated by over-exploitation and natural disorders.