The New Penguin History of the World (10 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

It is a little like speaking of ‘an educated man’: everyone can recognize one when they see him, but not all educated men are recognized as such by all observers, nor is a formal qualification (a university degree, for example) either a necessary or infallible indicator. Dictionary definitions are of no help in pinning down ‘civilization’, either. That of the

Oxford English Dictionary

is indisputable but so cautious as to be useless: ‘a developed or advanced state of human society’. What we have still to make

up our minds about is

how far

developed or advanced and along what lines.

Some have said that a civilized society is different from an uncivilized society because it has a certain attribute – writing, cities, monumental building have all been suggested. But agreement is difficult and it seems safer not to rely on any such single test. If, instead, we look at examples of what everyone has agreed to call civilizations and not at the marginal and doubtful cases, then it is obvious that what they have in common is complexity. They have all reached a level of elaboration which allows much more variety of human action and experience than even a well-off primitive community. Civilization is the name we give to the interaction of human beings in a very creative way, when, as it were, a critical mass of cultural potential and a certain surplus of resources have been built up. In civilization this releases human capacities for development at quite a new level and in large measure the development which follows is self-sustaining. This is somewhat abstract and it is time to turn to examples.

Somewhere in the fourth millennium

BC

is the starting-point of the story of civilizations and it will be helpful to set out a rough chronology. We begin with the first recognizable civilization in Mesopotamia. The next example is in Egypt, where civilization is observable at a slightly later date, perhaps about 3100

BC

. Another marker in the Near East is ‘Minoan’ civilization which appears in Crete in about 2000

BC

, and from that time we can disregard questions of priorities in this part of the world: it is already a complex of civilizations in interplay with one another. Meanwhile, further east and perhaps around 2500

BC

, another civilization has appeared in India and it is to some degree literate. China’s first civilization starts later, towards the middle of the second millennium

BC

. Later still come the meso-Americans. Once we are past about 1500

BC

, though, only this last example is sufficiently isolated for interaction not to be a big part of explaining what happens. From that time, there are no civilizations to be explained which appear without the stimulus, shock or inheritance provided by others which have appeared earlier. For the moment, then, our preliminary sketch is complete enough at this point.

About these first civilizations (whose appearance and shaping is the subject-matter of the next few chapters) it is very difficult to generalize. Of course they all show a low level of technological achievement, even if it is astonishingly high by comparison with that of their uncivilized predecessors. To this extent their shape and development were still determined much more than those of our own civilization by their setting. Yet they had begun to nibble at the restraints of geography. The topography of the world was already much as it is today; the continents were set in

the forms they now have and the barriers and channels to communication they supplied were to be constants, but there was a growing technological ability to exploit and transcend them. The currents of wind and water which directed early maritime travel have not changed much, and even in the second millennium

BC

men were learning to use them and to escape from their determining force.

This suggests, correctly, that at a very early date the possibilities of human interchange were considerable. It is therefore unwise to dogmatize about civilization appearing in any standard way in different places. Arguments have been put forward about favourable environments, river valleys for example: obviously, their rich and easily cultivated soils could support fairly dense populations of farmers in villages which would slowly grow into the first cities. This happened in Mesopotamia, Egypt, the Indus valley and China. But cities and civilizations have also arisen away from river valleys, in Meso-America, Minoan Crete and, later, in Greece. With the last two, there is the strong likelihood of important influence from the outside, but Egypt and the Indus valley, too, were in touch with Mesopotamia at a very early date in their evolution. Evidence of such contact led at one time to the view put forward a few years ago that we should look for one central source of civilization from which all others came. This is not now very popular. There is not only the awkward case of civilization in the isolated Americas to deal with, but great difficulty in getting the timetable of the supposed diffusion right, as more and more knowledge of early chronology is acquired by the techniques of radio-carbon dating.

The most satisfactory answer appears to be that civilization was likely always to result from the coming together of a number of factors predisposing a particular area to throw up something dense enough to be recognized later as civilization, but that different environments, different influences from outside and different cultural inheritances from the past mean that men did not move in all parts of the world at the same pace or even towards the same goals. The idea of a standard pattern of social ‘evolution’ was discredited even before the idea of ‘diffusion’ from a common civilizing source. Clearly, a favourable geographical setting was essential; in the first civilizations everything rested on the existence of an agricultural surplus. But another factor was just as important – the capacity of the peoples on the spot to take advantage of an environment or rise to a challenge, and here external contacts may be as important as tradition. China seems at first sight almost insulated from the outside, but even there possibilities of contact existed. The way in which different societies generate the critical mass of elements necessary to civilization therefore remains very hard to pin down.

It is easier to say something generally true about the marks of early civilization than about the way it happened. Again, no absolute and universal statements are plausible. Civilizations have existed without writing, useful as it is for storing and using experience. More mechanical skills have been very unevenly distributed, too: the meso-Americans carried out major building operations with neither draught animals nor the wheel, and the Chinese knew how to cast iron nearly fifteen hundred years before Europeans. Nor have all civilizations followed the same patterns of growth; there are wide disparities between their staying-power, let alone their successes.

None the less, early civilizations, like later ones, seem to have a common positive characteristic in that they change the human scale of things. They bring together the cooperative efforts of more men and women than in earlier societies and usually do this by physically bringing them together in larger agglomerations, too. Our word ‘civilization’ suggests, in its Latin roots, a connection with urbanization. Admittedly, it would be a bold man who was willing to draw a precise line at the moment when the balance tipped from a dense pattern of agricultural villages clustered around a religious centre or a market to reveal the first true city. Yet it is perfectly reasonable to say that more than any other institution the city has provided the critical mass which produces civilization and that it has fostered innovation better than any other environment so far. Inside the city the surpluses of wealth produced by agriculture made possible other things characteristic of civilized life. They provided for the upkeep of a priestly class which elaborated a complex religious structure, leading to the construction of great buildings with more than merely economic functions, and eventually to the writing down of literature. Much bigger resources than in earlier times were thus allocated to something other than immediate consumption and this meant a storing of enterprise and experience in new forms. The accumulated culture gradually became a more and more effective instrument for changing the world.

One change is quickly apparent: in different parts of the world men grew more unlike one another. The most obvious fact about early civilizations is that they are startlingly different in style, but because it is so obvious we usually overlook it. The coming of civilization opens an era of ever more rapid differentiation – of dress, architecture, technology, behaviour, social forms and thought. The roots of this obviously lie in prehistory, when there already existed men with different lifestyles, different patterns of existence, different mentalities, as well as different physical characteristics. But this was no longer merely the product of the natural endowment as environment, but of the creative power of civilization itself. Only with the

rise to dominance of Western technology in the twentieth-century has this variety begun to diminish. From the first civilizations to our own day there have always been alternative models of society available, even if they knew little of one another.

Much of this variety is very hard to recover. All that we can do in some instances is to be aware that it is there. At the beginning there is still little evidence about the life of the mind except institutions so far as we can recover them, symbols in art and ideas embodied in literature. In them lie presuppositions which are the great coordinates around which a view of the world is built – even when the people holding that view do not know they are there (history is often the discovery of what people did not know about themselves). Many such ideas are irrecoverable, and even when we can begin to grasp the shapes which defined the world of men living in the old civilizations, a constant effort of imagination must be made to avoid the danger of falling into anachronism which surrounds us on every side. Even literacy does not reveal very much of the minds of creatures so like and yet so unlike ourselves.

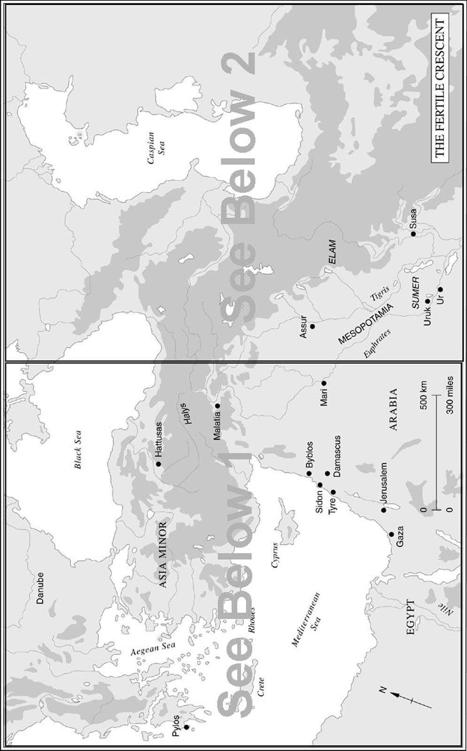

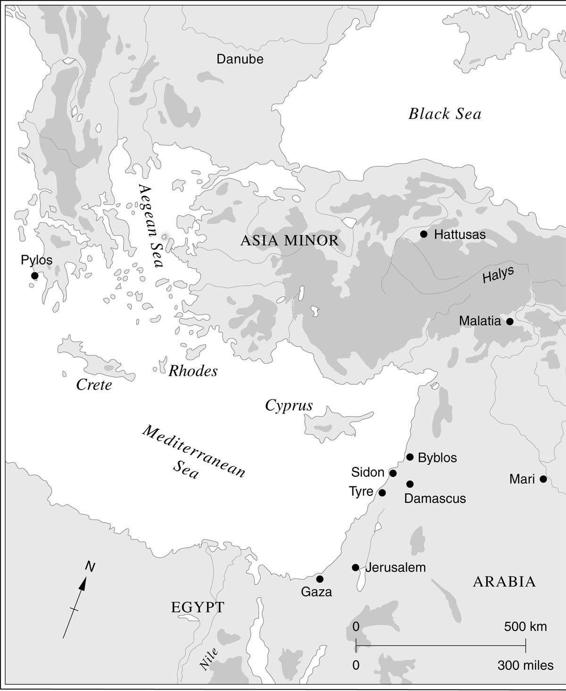

It is in the Near East that the stimulating effects of different cultures upon one another first become obvious and no doubt it is much of the story of the appearance of the earliest civilizations there. A turmoil of racial comings and goings for three or four thousand years both enriched and disrupted this area, where our history must begin. The Fertile Crescent was to be for most of historic times a great crucible of cultures, a zone not only of settlement but of transit, through which poured an ebb and flow of people and ideas. In the end this produced a fertile interchange of institutions, language and belief from which stems much of human thought and custom even today.

Why this began to happen cannot exactly be explained, but the overwhelming presumption must be that the root cause was over-population in the lands from which the intruders came. Over-population may seem a paradoxical notion to apply to a world whose whole population in about 4000

BC

has been estimated only at between eighty and ninety millions – that is, about the same as Germany’s today. In the next four thousand years it grew by about 50 per cent to about one hundred and thirty millions; this implies an annual increase almost imperceptible by comparison with what we now take for granted. It shows both the relative slowness with which our species added to its power to exploit the natural world and how much and how soon the new possibilities of civilization had already reinforced man’s propensity to multiply and prosper by comparison with prehistoric times.

Such growth was still slight by later standards because it was always based on a very fragile margin of resources and it is this fragility which justifies talk of over-population. Drought or desiccation could dramatically and suddenly destroy an area’s capacity to feed itself and it was to be thousands of years before food could easily be brought from elsewhere. The immediate results must often have been famine, but in the longer run there were others more important. The disturbances which resulted were the prime movers of early history; climatic change was still at work as a determinant, though now in much more local and specific ways. Droughts, catastrophic storms, even a few decades of marginally lower or higher temperatures, could force peoples to get on the move and so help to bring on civilization by throwing together peoples of different tradition. In collision and cooperation they learnt from one another and so increased the total potential of their societies.