The New Penguin History of the World (5 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

Another important physiological change is the loss of oestrus by the female hominid. We do not know when this happened, but after it had been completed her sexual rhythm was importantly differentiated from that of other animals. Man is the only animal in which the mechanism of the oestrus (the restriction of the female’s sexual attractiveness and receptivity to the limited periods in which she is on heat) has entirely disappeared. It is easy to see the evolutionary connection between this and the prolongation of infancy: if female hominids had undergone the violent disruption of their ordinary routine which the oestrus imposes, their offspring would have been periodically exposed to a neglect which would have made their survival impossible. The selection of a genetic strain which dispensed with oestrus, therefore, was essential to the survival of the species; such a strain must have been available, though the process in which it emerged may have taken a million or a million and a half years because it cannot have been effected consciously.

Such a change has radical implications. The increasing attractiveness and receptivity of females to males make individual choice much more significant in mating. The selection of a partner is less shaped by the rhythm of nature; we are at the start of a very long and obscure road which leads to the idea of sexual love. Together with prolonged infant dependency, the new possibilities of individual selection point ahead also to the stable and enduring family unit of father, mother and offspring, an institution unique to mankind. Some have even speculated that incest taboos (which are in practice well-nigh universal, however much the precise identification of the prohibited relationships may vary) originate in the recognition of the dangers presented by socially immature but sexually adult young males for long periods in close association with females who are always potentially sexually receptive.

In such matters it is best to be cautious. The evidence can take us only a very little way. Moreover, it is drawn from a very long span of time, a huge period which would have given time for considerable physical, psychological and technological evolution. The earliest forms of

Homo erectus

may not have been much like the last, some of whom have been classified by some scientists as archaic forms of the next evolutionary stage of the hominid line. Yet all reflections support the general hypothesis that the changes in hominids observable while

Homo erectus

occupies the centre of our stage were especially important in defining the arcs within which humanity was to evolve. He had unprecedented capacity to manipulate his environment, feeble though his handhold on it may seem to us. Besides the hand-axes which make possible the observation of his cultural traditions, late forms of

Homo erectus

left behind the earliest surviving traces of constructed dwellings (huts, sometimes fifty feet long, built of branches,

with stone-slab or skin floors), the earliest worked wood, the first wooden spear and the earliest container, a wooden bowl. Creation on such a scale hints strongly at a new level of mentality, at a conception of the object formed before manufacture is begun, and perhaps an idea of process. Some have argued far more. In the repetition of simple forms, triangles, ellipses and ovals, in huge numbers of examples of stone tools, there has been discerned intense care to produce regular shapes which does not seem proportionate to any small gain in efficiency which may have been achieved. Can there be discerned in this the first tiny budding of the aesthetic sense?

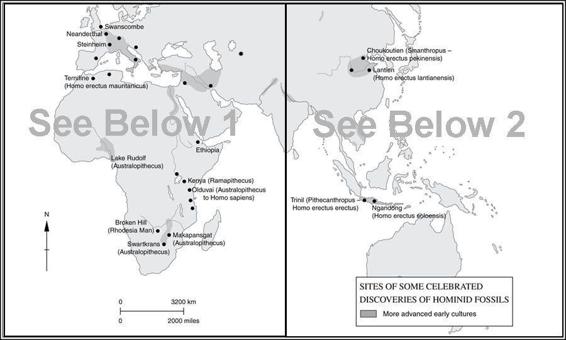

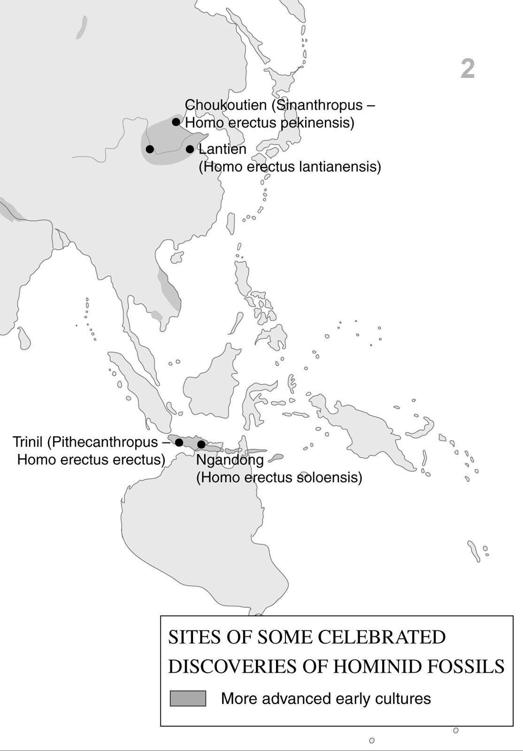

The greatest of prehistoric technical and cultural advances was made when some of these creatures learnt how to manage fire. Until recently, the earliest available evidence of its use came from China, and probably from between three and five hundred thousand years ago. But very recent discoveries in the Transvaal have provided evidence, convincing to many scholars, that hominids there were using fire well before that. It remains fairly certain that

Homo erectus

never learnt how to

make

fire and that even his successors did not for a long time possess this skill. That he knew how to use it, on the other hand, is indisputable. The importance of this knowledge is attested by the folklore of many later peoples; in almost all of them a heroic figure or magical beast first seizes fire. A violation of the supernatural order is implied: in the Greek legend Prometheus steals the fire of the gods. This is suggestive, not solid, but perhaps the first fire was taken from outbreaks of natural gas or volcanic activity. Culturally, economically, socially and technologically, fire was a revolutionary instrument – if we again remember that a prehistoric ‘revolution’ took millennia. It brought the possibility of warmth and light and therefore of a double extension of the habitable environment, into the cold and into the dark. In physical terms, one obvious expression of this was the occupation of caves. Animals could now be driven out and kept out by fire (and perhaps the seed lies here of the use of fire to drive big game in hunting). Technology could move forward: spears could be hardened in fires and cooking became possible, indigestible substances such as seeds becoming sources of food and distasteful or bitter plants edible. This must have stimulated attention to the variety and availability of plant life; the science of botany was stirring without anyone knowing it.

Fire must have influenced mentality more directly, too. It was another factor strengthening the tendency to conscious inhibition and restraint, and therefore their evolutionary importance. The focus of the cooking fire as the source of light and warmth had also the deep psychological power which it still retains. Around the hearths after dark gathered a community

almost certainly already aware of itself as a small and meaningful unit against a chaotic and unfriendly background. Language – of whose origins we as yet know nothing – would have been sharpened by a new kind of group intercourse. The group itself would be elaborated, too, in its structure. At some point, fire-bearers and fire specialists appeared, beings of awesome and mysterious importance, for on them depended life and death. They carried and guarded the great liberating tool, and the need to guard it must sometimes have made them masters. Yet the deepest tendency of this new power always ran towards the liberation of mankind. Fire began to break up the iron rigidity of night and day and even the discipline of the seasons. It thus carried further the breakdown of the great objective natural rhythms which bound our fireless ancestors. Behaviour could be less routine and automatic. There is even a discernible possibility of leisure.

Big-game hunting was the other great achievement of

Homo erectus

. Its origins must lie far back in the scavenging which turned vegetarian hominids into omnivores. Meat-eating provided concentrated protein. It released meat-eaters from the incessant nibbling of so many vegetarian creatures, and so permitted economies of effort. It is one of the first signs that the capacity for conscious restraint is at work when food is being carried home to be shared tomorrow rather than consumed on the spot today. At the beginning of the archaeological record, an elephant and perhaps a few giraffes and buffaloes were among the beasts whose scavenged meat was consumed at Olduvai, but for a long time the bones of smaller animals vastly preponderate in the rubbish. By about three hundred thousand years ago the picture is wholly altered.

This may be where we can find a clue to the way by which

Australopithecus

and his relatives were replaced by the bigger, more efficient

Homo erectus

. A new food supply permits larger consumption but also imposes new environments: game has to be followed if meat-eating becomes general. As the hominids become more or less parasitic upon other species there follows further exploration of territory and new settlements, too, as sites particularly favoured by the mammoth or woolly rhinoceros are identified. Knowledge of such facts has to be learnt and passed on; technique has to be transmitted and guarded, for the skills required to trap, kill and dismember the huge beasts of antiquity were enormous in relation to anything which preceded them. What is more, they were cooperative skills: only large numbers could carry out so complex an operation as the driving – perhaps by fire – of game to a killing-ground favourable because of bogs in which a weighty creature would flounder, or because of a precipice, well-placed vantage points, or secure platforms for the hunters. Few weapons were available to supplement natural traps and, once dead, the

victims presented further problems. With only wood, stone and flint, they had to be cut up and removed to the home base. Once carried home, the new supplies of meat mark another step towards the provision of leisure as the consumer is released for a time from the drudgery of ceaselessly rummaging in his environment for small, but continuously available, quantities of nourishment.

It is very difficult not to feel that this is an epoch of crucial significance. Considered against a background of millions of years of evolution, the pace of change, though still unbelievably slow in terms of later societies, is quickening. These are not men as we know them, but they are beginning to be manlike creatures: the greatest of predators is beginning to stir in his cradle. Something like a true society, too, is dimly discernible, not merely in the complicated cooperative hunting enterprises, but in what this implies in passing on knowledge from generation to generation. Culture and tradition are slowly taking over from genetic mutation and natural selection as the primary sources of change among the hominids. It is the groups with the best ‘memories’ of effective techniques which will carry forward evolution. The importance of experience was very great, for knowledge of methods which were likely to succeed rested upon it, not (as increasingly in modern society) on experiment and analysis. This fact alone would have given new importance to the older and more experienced. They knew how things were done and what methods worked and they did so at a time when the home base and big-game hunting made their maintenance by the group easier. They would not have been very old, of course. Very few can have lived more than forty years.

Selection also favoured those groups whose members not only had good memories but the increasing power to reflect upon it given by speech. We know very little about the prehistory of language. Modern types of language can only have appeared long after

Homo erectus

disappeared. Yet some sort of communication must have been used in big-game hunting, and all primates make meaningful signals. How early hominids communicated may never be known, but one plausible suggestion is that they began by breaking up calls akin to those of other animals into particular sounds capable of rearrangement. This would give the possibility of different messages and may be the remote tap-root of grammar. What is certain is that a great acceleration of evolution would follow the appearance of groups able to pool experience, to practise and refine skills, to elaborate ideas through language. Once more, we cannot separate one process from others: better vision, an increased physical capacity to deal with the world as a set of discrete objects and the multiplication of artifacts by using tools were all going on simultaneously over the hundreds of thousands of years

in which language was evolving. Together they contributed to a growing extension of mental capacity until one day conceptualization became possible and abstract thought appeared.