The New Penguin History of the World (8 page)

Read The New Penguin History of the World Online

Authors: J. M. Roberts,Odd Arne Westad

3

The Possibility of Civilization

Human beings have existed for at least twenty times as long as the civilizations they have created. The waning of the last Ice Age allowed the long march to civilization to be completed and is the immediate prelude to History. Within five or six thousand years a succession of momentous changes took place of which unquestionably the most important was an increase in food supply. Nothing so sharply accelerated human development or had such widespread results until the changes called industrialization which have gone on over the last three centuries.

One scholar summed up these changes which mark the end of prehistory as the ‘Neolithic revolution’. Here begins another little tangle of potentially misleading terminology, though the last we need consider in prehistory. Archaeologists follow the Palaeolithic era by the Mesolithic and that by the Neolithic (some add a fourth, the Chalcolithic, by which they mean a phase of society in which artifacts of stone and copper are in simultaneous use). The distinction between the first two is really of interest only to the specialist, but all these terms describe cultural facts; they identify sequences of artifacts which show growing resources and capacities. Only the term ‘Neolithic’ need concern us. It means, at its narrowest and most precise, a culture in which ground or polished stone tools replace chipped ones (though other criteria are sometimes added to this). This may not seem so startling a change as to justify the excitement over the Neolithic which has been shown by some prehistorians, far less talk of a ‘Neolithic revolution’. In fact, though the phrase is still sometimes used, it is unsatisfactory because it has had to cover too many different ideas. None the less, it was an attempt to pin down an important and complex change which took place with many local variations and it is worthwhile to try to assess its general significance.

We can start by noting that even in the narrowest technological sense, the Neolithic phase of human development does not begin, flower or end everywhere at the same time. In one place it may last thousands of years longer than in another and its beginnings are separated from what went

before, not by a clear line but by a mysterious zone of cultural change. Then, within it, not all societies possess the same range of skills and resources; some discover how to make pottery, as well as polished stone tools, others go on to domesticate animals and begin to gather or raise cereal crops. Slow evolution is the rule and not all societies had reached the same level by the time literate civilization appears. Nevertheless, Neolithic culture is the matrix from which civilization appears and provides the preconditions on which it rests, and they are by no means limited to the production of the highly finished stone tools which gave the phase its name.

We must also qualify the word ‘revolution’ when discussing this change. Though we leave behind the slow evolutions of the Pleistocene and move into an accelerating era of prehistory, there are still no clear-cut divisions. They are pretty rare in later history; even when they try to do so, few societies ever wholly break with their past. What we can observe is a slow but radical transformation of human behaviour and organization over more and more of the world, not a sudden new departure. It is made up of several crucial changes which make the last period of prehistory identifiable as a unity, whatever we call it.

At the end of the Upper Palaeolithic, Man existed physically much as we know him. He was, of course, still to change somewhat in height and weight, most obviously in those areas of the world where he gained in stature and life expectancy as nutrition improved. In the Old Stone Age it was still unlikely that a man or a woman would reach an age of forty and if they did then they were likely to live pretty miserable lives, in our eyes prematurely aged, tormented by arthritis, rheumatism and the casual accidents of broken bones or rotting teeth. This would only slowly change for the better. The shape of the human face would go on evolving, too, as diet altered. (It seems to be only after

AD

1066 that the edge-to-edge bite gave way among Anglo-Saxons to the overbite which was the ultimate consequence of a shift to more starch and carbohydrate, a development of some importance for the later appearance of the English.)

The physical types of men differed in different continents, but we cannot presume that capacities did. In all parts of the world

Homo sapiens sapiens

was showing great versatility in adapting his heritage to the climatic and geographical upheavals of the ebbing phase of the last Ice Age. In the beginnings of settlements of some size and permanence, in the elaboration of technology and in the growth of language and the dawn of characterization in art lay some of the rudimentary elements of the compound which was eventually to crystallize as civilization. But much more than these were needed. Above all, there had to be the possibility of some sort of economic surplus to daily requirements.

This was hardly conceivable except in occasional, specially favourable areas of the hunting and gathering economy which sustained all human life and was the only one known to human beings until about ten thousand years ago. What made it possible was the invention of agriculture.

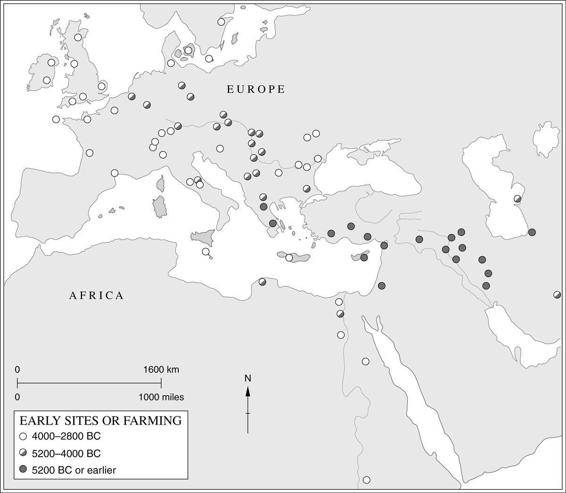

The importance of this was so great that it does seem to justify a strong metaphor and ‘farming revolution’ or ‘food-gathering revolution’ are terms whose meaning is readily clear. They single out the fact which explains why the Neolithic era could provide the circumstances in which civilizations could appear. Even a knowledge of metallurgy, which was spreading in some societies during their Neolithic phases, is not so fundamental. Farming truly revolutionized the conditions of human existence and it is the main thing to bear in mind when considering the meaning of Neolithic, a meaning once concisely summarized as ‘a period between the end of the hunting way of life and the beginning of a full metal-using economy, when the practice of farming arose and spread through most of Europe, Asia and North Africa like a slow-moving wave’. The essentials of agriculture are the growing of crops and the practice of animal husbandry. How these came about and at what places and times is more mysterious. Some environments must have helped more than others; while some peoples pursued game across plains uncovered by the retreating ice, others were intensifying the skills needed to exploit the new, prolific river valleys and coastal inlets rich in edible plants and fish. The same must be true of cultivation and herding. On the whole, the Old World of Africa and Eurasia was better off for animals which might be domesticated than what would later be called the Americas. Not surprisingly, then, agriculture began in more than one place and in different forms. It has been claimed that the earliest instance, based on the cultivation of primitive forms of millet and rice, occurred in south-east Asia, somewhere about 10,000

BC

. Yet for thousands of years, and until only a couple of centuries ago, the increase of human food supply was to come from methods already available, though only slowly discovered, and in rudimentary form, in prehistoric times. New land could be broken in for crops, elementary observation and selection began the conscious modification of species, plant forms were transferred to new locations, and labour was applied to cultivation through digging, draining and irrigating. These made possible a growth in food production which could sustain a slow and steady rise in human numbers until the great changes brought by chemical fertilizers and modern genetic science.

The accidents of survival and the direction of scholarly effort have meant until recently that much more was known about early agriculture in the Near East than about its possible precursors in further Asia. Rice may have been cultivated in the Yangtze valley as early as 7000

BC

. None the less, there is good reason to regard the Near East as a crucial zone. Both the predisposing conditions and the evidence point to the region later called the ‘Fertile Crescent’ as especially significant; this is the arc of territory running northwards from Egypt through Palestine and the Levant, through Anatolia to the hills between Iran and the south Caspian to enclose the river valleys of Mesopotamia. Much of it now looks very different from the same area’s lush landscape when the climate was at its best, five thousand or so years ago. Wild barley and a wheatlike cereal then grew in southern Turkey and emmer, a wild wheat, in the Jordan valley. Egypt enjoyed enough rain for the hunting of big game well into historical times, and elephants were still to be found in Syrian forests in 1000

BC

. The region today is still fertile by comparison with the deserts which encircle it, but in prehistoric times it was even more favoured. The cereal grasses which are the ancestors of later crops have been traced back furthest in these lands. There is evidence of the harvesting, though not necessarily of the cultivating, of wild grasses in Asia Minor in about 9500

BC

. There, too, the afforestation which followed the end of the last Ice Age seems to have presented a manageable challenge; population pressure might well have

stimulated attempts to extend living-space by clearing and planting when hunting-gathering areas became overcrowded. From this region the new foods and the techniques for planting and harvesting them seem to have spread into Europe in about 7000

BC

. Within the region, of course, contacts were relatively easier than outside it; a date as early as 8000

BC

has been given to discoveries of bladed tools found in south-west Iran but made from obsidian which came from Anatolia. But diffusion need not have been the only process at work. Agriculture later appeared in the Americas, seemingly without any import of techniques from outside.

The jump from gathering wild cereals to planting and harvesting them seems marginally greater than that from driving game for hunting to herding, but the domestication of animals was almost as momentous. The first traces of the keeping of sheep come from northern Iraq, in about 9000

BC

. Over such hilly, grassy areas the wild forebears of the Jersey cow and the Gloucester Old Spot pig roamed untroubled for thousands of years except by occasional contact with their hunters. Pigs, it is true, could be found all over the Old World, but sheep and goats were especially plentiful in Asia Minor and a region running across much of Asia itself. From their systematic exploitation would follow the control of their breeding and other economic and technological innovations. The use of skins and wool opened new possibilities; the taking of milk launched dairying. Riding and the use of animals for traction would come later. So would domestic poultry.

The story of mankind is now far past the point at which the impact of such changes can be easily grasped. Suddenly, with the coming of agriculture, the whole material fabric on which subsequent human history was to be based flashes into view, though not yet into existence. It was the beginning of the greatest of man’s transformations of the environment. In a hunting-gathering society thousands of acres are needed to support a family, whereas in primitive agricultural society about twenty-five acres is enough. In terms of population growth alone, a huge acceleration became possible. An assured or virtually assured food surplus also meant settlements of a new solidity. Bigger populations could live on smaller areas and true villages could appear. Specialists not engaged in food production could be tolerated and fed more easily while they practised their own skills. Before 9000

BC

there was a village (and perhaps a shrine) at Jericho. A thousand years later it had grown to some eight to ten acres of mud-brick houses with substantial walls.

It is a long time before we can discern much of the social organization and behaviour of early farming communities. It seems possible that at this time, as much as at any other, local divisions of mankind were decisively

influential. Physically, humanity was more uniform than ever, but culturally it was diversifying as it grappled with different problems and appropriated different resources. The adaptability of different branches of

Homo sapiens

in the conditions left behind after the retreat of the last Ice Age is very striking and produced variations in experience unlike those following earlier glaciations. They lived for the most part in isolated, settled traditions, in which the importance of routine was overwhelming. This would give new stability to the divisions of culture and race which had appeared so slowly throughout Palaeolithic times. It would take much less time in the historical future which lay ahead for these local peculiarities to crumble under the impact of population growth, speedier communication and the coming of trade – a mere ten thousand years, at most. Within the new farming communities it seems likely that distinctions of role multiplied and new collective disciplines had to be accepted. For some people there must have been more leisure (though for others actually engaged in the production of food, leisure may well have diminished). It certainly seems likely that social distinctions became more marked. This may be connected with new possibilities as surpluses became available for barter which led eventually to trade.