The New Policeman (5 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

“I don’t know,” said Helen. “There isn’t really anything I want.”

“Good,” said Ciaran. “That’s easy then.”

“Time,” said Helen. “That’s what I want. Time.”

“I see,” said Ciaran thoughtfully. “And how would madam like her time served? A week in the Algarve perhaps? Two weeks in Spiddal?”

Helen shook her head. “Not that kind of time. Ordinary, run-of-the-mill time. A few more hours in every day.”

“Tall order,” said Marian.

“Not possible,” said J.J.

“Never say never,” said Ciaran. “Where there’s a will there’s a what?”

“A big family argument, usually,” said Marian.

“There’s always a way,” said Ciaran. “Anything can be done. So that’ll be J.J.’s present. What do you want from the rest of us?”

But Helen wasn’t in the mood. Her mind was on what J.J. had said earlier, about her grandfather. It was time for him to learn a bit of family history.

Ciaran and Helen went out to get the goats in, leaving J.J. and Marian to clear the kitchen and wash up. J.J. waited until the worst of the clattering was over, then said, as casually as he could, “What are the fellas wearing to the clubs these days?”

His sister saw straight through him. “Clubs? Are you going clubbing?”

“No! I was just wondering, that’s all.”

“Are you going tomorrow? Have you got a girlfriend?”

“Of course I haven’t got a girlfriend!”

“But you’re going clubbing? Are you? Seriously? Does Mum know?”

There was no point in trying to pull the wool over Marian’s eyes. Nothing escaped her. Besides, it was suddenly a great relief to have a confidante.

“Not yet,” said J.J. “Don’t tell her, will you? I might not go at all.”

“You have to tell her. You can’t just dump her in it for the dance.”

“Why not? She doesn’t need me. Herself and Phil did it for years on their own.”

“It’s different now. You’re part of the band. Half the tunes they play are your tunes.”

“She doesn’t need me, Maz. Anyway, if you’re so worried about it, why don’t you play?”

“Because I’m not good enough, that’s why.”

“You are. You’re every bit as good as I was when I started doing it.”

It was true. He and Helen were always trying to persuade her to join in. She already had nearly as many medals and trophies as J.J., and she was still in primary school. She was still dancing and she would, J.J. knew, carry on when she went to secondary. Marian would never be influenced by what other people thought of her.

“So?” he said. “What do fellas wear to go clubbing?”

Marian shrugged. “I don’t know. And if I did I wouldn’t tell you.”

J.J. had no chance to press her. Ciaran was at the front door, bellowing. Marian looked at the clock, grabbed her script, and raced out.

J.J. finished the washing-up on his own. His fiddle was on the settle where he had left it. He resisted the temptation to pick it up, and when he had finished cleaning up the kitchen he put his wet clothes in the dryer and went upstairs to have another think about what to wear.

His new sneakers would do, anyway. They weren’t a fashionable brand—Ciaran wouldn’t allow anything made by sweatshop labor into the house—but they were cool enough. That was one decision made, but J.J. found he couldn’t get any further. He had no sense of fashion at all. Helen still bought all his clothes. Should he ring Jimmy and ask him? Would he sound like a fool? Probably. But it would be better than looking like one. He went downstairs to the phone, but he was cut off at the pass by Helen, coming back in from the milking.

“Are you busy?” she asked him.

Those words invariably preceded a request for help with something. J.J. searched for an excuse, but he was too slow. He was wrong, this time, as well.

“I wanted to have a word with you,” Helen said. “About my grandfather.”

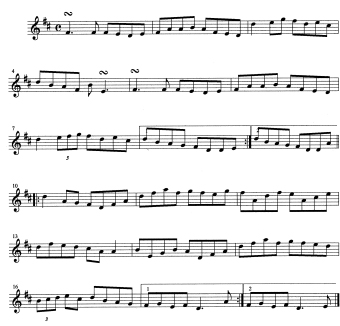

THE WISE MAID

Trad

The new policeman was off duty, driving along the narrow roads that ran through the heart of the Burren. He was driving very slowly, partly because he hadn’t been driving very long and wasn’t at all comfortable with the idea, and partly because he was looking for something. What it was that he was looking for was unclear to him, but he assumed, or at least he hoped, that if he saw it he would recognize it.

He pulled off the road to allow another car to go by. It didn’t need the whole width of the road, but Larry felt it was probably safer to let it have it anyway. Then, since he had found a convenient place to leave the car for a while, he decided to get out and take a stroll around. He climbed the nearest wall and

wandered across the rocks, stepping from one slab to the next, avoiding the treacherous cracks between them. As he walked he wondered if it would be appropriate to pay a visit to Green’s that evening. When he thought about Sergeant Early and Garda Treacy he was fairly sure what their reaction would be. But he was off duty. There was nothing in the rule book, as far as he could remember, that made the local pubs off limits to him.

He turned to his left and climbed a rocky hillock. When he got to the top, a spectacular view revealed itself: gray hill after gray hill stretching away until they met the hazy horizon. Westward the sun, huge and yellow, was sinking fast. The sight reminded him of home and that elusive thing he had come here in order to find. It was like looking for a needle in a haystack. No. Needles in haystacks didn’t come close to describing the magnitude of the task he had in hand.

And time was slipping away much, much too fast.

THE STONY STEPS

Trad

J.J. was curious about what Helen had to say, but at the same time he dreaded it.

“Let’s have a cup of tea,” said Helen.

Tea was their fuel and their comfort, snatched wherever possible during their frantic days. When the range was lit in the winter, the kettle was always sitting on it, ready for when it would next be needed. That day hadn’t been cold enough for the range, but the sitting room was always inclined to be damp, so while Helen boiled the electric kettle and made the tea, J.J. lit a few briquettes in the fireplace. Then, without telling Helen, he took the phone off the hook. Marian was staying overnight with a friend when her drama group was over, and Ciaran was going straight on to Galway after dropping her, to a meeting of the

local antiwar group. Provided no one dropped by the house, J.J. and his mother might get a rare chance to talk in peace.

The light was almost gone from the day. While the tea brewed in front of the fledgling flames, J.J. drew the curtains and Helen rummaged in the cupboard against the wall beside the piano. She returned with a large, tatty brown envelope, and while J.J. poured the tea, she examined its contents. When he handed her a cup, she gave him a dog-eared black-and-white photograph, then pulled her chair around beside his so that they could look at it together.

The frame of the picture was filled by the front of the house, the Liddy house where they were sitting now. In those days it would have been fairly new and, in comparison to the average Irish farmhouse, fairly grand. The Liddys then, if not now, were influential people. In front of the house, seven people were standing: three men, a woman, and three children—a girl and two boys. All of them held musical instruments. All of them wore serious, even stern expressions. From what J.J. had seen of old photographs, that was not unusual.

“It was taken in 1935,” said Helen. “The woman with the fiddle was my grandmother, your

great-grandmother. This fellow here, beside her, is Gilbert Clancy.”

“Gilbert Clancy? Let’s see.” J.J. had heard about Gilbert Clancy before. He had known the legendary blind piper, Garrett Barry, and had passed on a large part of his repertoire to his better-known son, Willie Clancy.

“Gilbert was a great friend of the Liddys,” said Helen. “He was often in this house.”

“Was Willie ever here?”

“Plenty of times,” said Helen. She pointed to another of the men in the photograph. “That’s your great-grandfather. He made that flute himself, out of the spoke of a cart wheel.”

“Are you serious?”

“God’s truth,” said Helen.

J.J. held the photograph closer to the light and examined the instrument. The focus was sharp, but the figures were too far from the lens for the details to be clear. He could see, though, that the flute was very plain, with no decoration of any kind. If it had joints, they were invisible.

“He wasn’t known as an instrument maker,” Helen went on, “but he made a few flutes and whistles in his time. Micho Russell told me once that he had played a whistle my grandfather made and he had liked it

enough to try to buy it. But of all the instruments he made, that flute there was the best. He loved it. Could hardly stop playing it. Wherever he went, that flute went with him. They say that he was so afraid of losing it that he engraved his name on it, up at the top.”

“What happened to it?” asked J.J. “Where is it now?”

“That’s the story I want to tell you, J.J. It’s a sad story, but when you hear it you might understand why music has always been so important to me. The music and the Liddy name.”

Helen topped up their mugs and leaned back in her chair. “There were always dances in this house, going way back. As long as there was music, the Liddys have been musicians. You’d think it was simple, wouldn’t you, looking at it now? A harmless pastime? Better than harmless, even. Healthy. But in those days dance music had its enemies.”

“What kind of enemies?” asked J.J.

“Powerful ones,” said Helen. “The clergy.”

“What—the priests?”

“The priests, yes. And above them the bishops, and above them the cardinals.”

“But why?”

“It’s not an easy question. There’s an obvious answer, which is that young people gathered together from all

over the parish—beyond it, even. The dances were great social occasions. Men and women mixed together and got to know each other. Pretty much like the clubs and discos now, I suppose. Everyone would have a few drinks and let their hair down a bit. The clergy maintained that the dances led to immoral behavior.”

“People still say that,” said J.J., “about discos and clubs.” He spotted a window of opportunity opening. Would now be a good moment to tell her?

“They do,” said Helen. “And I suppose they’re right, according to their own frames of reference. Things go on in those places that every parent would have reason to worry about.”

J.J.’s window slammed shut. Helen reached out and dropped another briquette onto the fire, sending up a little plume of sparks.

“But there was another, less obvious reason that the priests, or some of them at least, hated our music. The Irish—the majority of us anyway—have been Catholic for hundreds of years. If you look at it simplistically, you could say that the priests wielded total control over our lives and our beliefs. But the truth wasn’t so simple.”

“It never is,” said J.J.

“It never is,” Helen repeated. “There were older,

more primitive beliefs in Ireland that went back even further than the Church. They went back thousands, not hundreds of years. In some small ways they’re still with us today.”

“Like what?” said J.J.

“The fairy folk,” said Helen, “and all the stories and superstitions that surround them.”

“But that’s not still with us,” said J.J. “Nobody believes in any of that these days.”

Helen shrugged. “Maybe not. But remember what Anne Korff was talking about today? The forts? How the farmers won’t clear them from the land?”

“They’re historical monuments, aren’t they?”

“Perhaps that’s all it is now,” said Helen. “But I’m not sure. That one in our top meadow isn’t recorded anywhere. It doesn’t have any kind of preservation order on it. So will you bulldoze it when you take over the farm?”

J.J. thought about it and found that he wouldn’t. Deep down, in a place in himself that he had never visited, he found that he was as superstitious about the fort as his mother was; as her mother and her grandparents would have been. He shook his head.