The New Policeman (6 page)

Authors: Kate Thompson

“No,” said Helen. “And you don’t even believe in fairies. My mother did, you know. And in my grand

parents’ time everyone did. People still saw them, or believed that they did. And loads of people claimed to have heard their music.”

“But that’s crazy stuff,” said J.J.

“Maybe,” said Helen. “Maybe not. In any event, the priests were of your opinion. It was more than crazy, according to them. It was dangerous and subversive. But they couldn’t knock those old beliefs out of people, no matter how hard they tried or what hellfire they threatened them with. The fairies and the country people just went too far back together. And the one thing that everyone agreed upon, whether they had heard it themselves or not, was that our music—our jigs and our reels and our hornpipes and our slow airs—was given to us by the fairies.”

A cold little shiver trickled down J.J.’s spine. It wasn’t the first time he had heard the old association, but it was the first time it had touched him.

“So,” Helen went on, “the priests could do nothing to stamp out the fairy beliefs. They had tried and failed for long enough. But there was one thing they might be able to get rid of, and that was the music. If they succeeded in that, there was a chance that the rest of the superstitions would follow of their own accord.

“They weren’t all like that. There were some priests

who were very tolerant of the old traditions. There were even some who played a few tunes themselves. But there were others who broke up musical gatherings and dances wherever they found them and did their utmost to stamp out the music. Then, in 1935, the year this photo was taken, they added a new, powerful weapon to their armory. It was called the Public Dance Hall Act.”

J.J. was losing interest. He got more than enough history at school. “What’s this got to do with your granddad?” he said.

“I’m getting there,” said Helen. “Basically, until then most of the dances had been like our céilís. They were held in people’s houses or sometimes, in summer, at a crossroads. People paid to get into them, to cover the cost of the drink and the musicians. There might even have been a bit of profit in it for the house owner, though that was never why we had dances here. But the new act, which was passed by the government under pressure from the Church, made the house dances illegal. From that time onward, all dances had to be held in the parish hall, where the priest could keep an eye on the goings-on. It nearly worked, too, because it wasn’t long before other kinds of music began to get popular. We very nearly lost our musical tradition.”

“But people could still play, couldn’t they? In the pub or in their houses?”

“They could, but sessions are a relatively new thing, you know—people playing tunes while other people sit around and talk. I don’t like it myself. This music is dance music, J.J. It always was. That’s why I made sure you and Maz learned to dance. Even if you never do it again, you understand the music from the inside out.”

J.J. nodded. He had been to a lot of fleadhs and heard a lot of people playing. You could almost always tell from their playing whether they knew how to dance or not.

“Anyway,” Helen went on, “the long and the short of it was that the house dances were in danger of dying out. You could hold a dance if you didn’t charge an entrance fee, but there weren’t many people around in those days who could afford to do that.”

“But the Liddys could,” said J.J.

“Yup. The Liddys could. We weren’t rich by modern standards, but we were pretty well off by the standards of those days. And we had one big advantage over a lot of the other houses that used to hold dances. We didn’t have to pay the musicians. We were the musicians.”

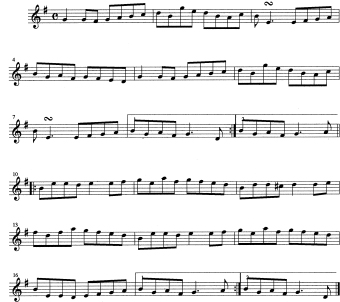

GARRETT BARRY’S JIG

Trad

The new policeman went into Kinvara, got a bite to eat in Rosaleen’s, and made his way down the street to Green’s. He was on the early side, he knew. Sessions never got going much before ten o’clock. He had thought long and hard about whether it would be better to arrive early or late and had eventually decided on early. If he arrived when the session had already started, there was a danger that the shock of being joined by a policeman would knock the spirit out of the music. Getting there early would give Mary Green a chance to get used to the idea, and with luck, he would be able to convince the musicians that he wasn’t there in any official capacity.

At the door he paused, his fiddle in his hand. Perhaps it wasn’t such a good idea after all? His

presence was sure to inhibit the others, and Mary Green would probably hunt them all out into the street at twelve o’clock on the dot. He would ruin it for everyone. Maybe it would be better if he just went home and had a tune there with the others, free from the tyranny of the licensing laws?

No. He’d better stay. He’d set out to investigate something, after all. There might be clues anywhere. You could never know what you might hear.

He met with a frosty reception in Green’s. Mary was a generous woman, but it was beyond even her powers of hospitality to make a man welcome when, just the previous night, he had raided her premises. Some of the same customers were in that evening, and it didn’t take them long to reveal Larry’s identity to the ones who didn’t yet know it. One of the musicians turned round the moment he set eyes on the policeman and went up the road to play in Winkles instead. The others stood around the bar and engaged in a game of musical politics that might have gone on all night if it hadn’t been for a piper who lived locally. He didn’t drink and he couldn’t abide standing around. He was there for the music, not for the politics, and he was always gone before closing time anyway.

“I suppose we’ll play a tune,” he said to Larry.

“I suppose we will,” said Larry.

By the end of the first set of tunes there wasn’t a musician left standing. Whatever his profession, Larry’s fiddle playing left little to be desired. No one in the room had ever heard anything quite like it. Within minutes everyone had tuned up their instruments and the music was off again.

Mary Green brought more drinks. Larry felt the music race in his blood, linking his past to his present, bringing him home. For the first time since he had arrived in Kinvara, the new policeman was happy.

THE TEETOTALLER

Trad

“This parish was unlucky,” said Helen. “Father Doherty was a good priest in a lot of ways, so I’ve been told, but he was one of the worst where the music was concerned. A Sunday hardly passed without him ranting from the pulpit about the terrible vengeance God would wreak on those who believed in fairies and danced to their evil tunes. Even before the act was passed, he walked the roads at night, barging into any house where he heard music and browbeating everyone he found there. He broke a man’s fiddle once, under his boot. But out of all his parishioners, there was none that made him as angry as my grandfather.

“The hatred was mutual. J.J.—” Helen paused. “Did I tell you he was called J.J.? That you were named after him?”

“You didn’t,” said J.J. “But someone else did.”

“Who?”

“Never mind. Go on.”

Helen hesitated, wondering whether to press him, then decided against it. “He used to bar the door against Father Doherty and play away while he battered on the door and yelled. Then, on Sundays, he used to turn up in the church and sit through all the tirades as if they didn’t concern him in the slightest. Father Doherty couldn’t take it. He was used to being obeyed. The act was barely made law when he turned the Liddys in for holding a house dance. They weren’t the only ones either. There were a good few prosecutions that year, and a lot of them were successful. People got stuck with fines they could never afford to pay. The act was working. But it didn’t work against the Liddys. People told my grandfather later that Father Doherty had threatened them with eternal damnation if they didn’t stand up in court and swear that they’d been charged an entrance fee at the door of the dance. But for all their fear of the priest and the power vested in him, there wasn’t one person who would betray the Liddys. That’s how highly the family was regarded in the parish back then.”

Helen stopped for a moment, and J.J. saw a look of

fierce pride in her eyes. Then it collapsed and she turned her gaze to the flames. “But that was before.”

J.J. waited. Helen took a deep breath. “The case was thrown out. My grandparents held a dance to celebrate. It was high summer and the nights were long and warm. The dancers spilled out of the house into the yard, and after a while the musicians followed them out there. Everyone said the craic was mighty. There had never been a dance to equal it. Until Father Doherty turned up.

“He was so furious that not even my grandfather could keep on playing. He was red in the face and shaking with rage.

“‘You think you got the better of me, don’t you?’ he said.

“Father Doherty was not a young man. My grandmother was concerned for him. Despite all that had happened, she didn’t want him to have a seizure, on her doorstep or anywhere else. She invited him to step inside the house and have a cup of tea.

“‘I’ll never again set foot in that iniquitous house,’ he said to her. ‘And I’ll tell you another thing as well. I will put an end to this devil’s music.’

“He snatched the flute out of my grandfather’s hand and marched out of the yard. My grandfather

ran after him, but he was—you have to believe this, J.J.—he was a gentle man. He loved that flute above all else that he owned, but he would not resort to violence to get it back. Father Doherty walked away from this house with the flute that night, seventy years ago, and that was the last time that anyone ever saw him.”

“What?” said J.J.

“He disappeared. He was never seen again.”

“But…you mean they never even found a body?”

Helen shook her head. “Nothing. To this day no one knows what happened to him. But unfortunately, people being what they are, a nasty rumor began to go around.”

“That your grandfather killed him?”

Helen nodded.

“And did he?” said J.J.

“Of course he didn’t.”

“How do you know?”

“I just know, J.J. He didn’t have it in him. He hated authority, but he wasn’t a murderer.”

“What happened to the flute?”

“Gone, too. It was never seen again.”

“That’s weird,” said J.J. “How could someone just disappear?”

“I don’t know any more than you do,” said Helen.

“It happens sometimes, though. People do disappear. They searched high and low for him, but they never found any trace.”

J.J. turned back to the photograph with renewed interest. His great-grandfather was a big man, but J.J. could see nothing in his face that suggested he was capable of such a violent crime.

“The parish was divided,” Helen went on. “A lot of people turned against the Liddys, but a lot more stayed loyal to us. Even so, for a long time after that midsummer’s night there wasn’t a note played in this house. It was more than a month later that Gilbert Clancy turned up in the yard. He had been far away when Father Doherty went missing and had only just heard about it. He listened while my grandfather told him the whole story. When he was finished, Gilbert said, ‘Well. That priest has succeeded in his aim, hasn’t he?’

“My grandfather asked him what he meant. When I was a child he told me the story many times, and what Gilbert said to him. ‘Your man has brought silence into one of the greatest houses for music that there ever was. He has taken more than your flute from you, J.J.’

“My grandfather sat and thought about that for a

long, long time. Then he got up and went out to the back room that he used to use for his workshop. By the time he came back, Gilbert Clancy was already warming up his flute and my grandmother’s fiddle had been taken down from the wall and dusted off.

“And from that day to this, J.J., there has always been music in this house.”

THE PRIEST AND HIS BOOTS