The Next Decade (32 page)

Stopping the violence from spreading north of the border is alone important enough to topple any president who fails to do so. Fortunately, not allowing violence to spread is in the interests of the cartels as well. They understand that significant violence in the United States would trigger a response that, while ineffective, would still hamper their business interests. In recognizing that the United States would neither move south nor effectively interfere with their trade otherwise, the drug cartels would be irrational to spread violence northward, and smugglers dealing in vast amounts of money are not irrational.

A final word must be included here about Canada, which of course shares the longest border with the United States and is America’s largest trading partner. Canada has been an afterthought to the United States since British interest in continental North America declined. It is not that Canada is not important to the United States; it is simply that Canada is locked into place by geography and American power.

Looking at a map, Canada appears to be a vast country, though in terms of populated territory it is actually quite small, with its population distributed in a band along the U.S. border. Many parts of Canada have a north-south orientation rather than an east-west one. In other words, their economic and social life is oriented toward the United States in contrast to Canada, which operates on an east-west basis.

The issue for Canada is that the United States is a giant market as well as source of goods. There is also a deep cultural affinity. This creates problems for Canadians, who see themselves as and want to be a distinct culture as well as country. But as with the rest of the world, Canada is under heavy pressure from American culture, and resistance is difficult.

For the Canadians, there are multiple fault lines in their confederation, the most important being the split between French-speaking Quebec and the rest of Canada, which is predominantly English-speaking. There was a serious separatist movement in the 1960s and 1970s, which won major concessions on the use of language, but it never achieved independence. Today that movement has moderated and independence is not on the table, although expanded autonomy might be.

For the United States, Canada itself poses no threats. The greatest danger would come if Canada were to ally with a major global power. There is only one conceivable scenario for this, and that is if Canada were to fragment. Given the degree of economic and social integration, it would be hard to imagine a situation in which a Canadian province would be able to shift relationships without disaster, or one in which the United States would permit close relations to develop between a province and a hostile power while continuing economic relations. The only case in which this would be imaginable is an independent Quebec, which might forgo economic relations for cultural or ideological reasons.

In the next decade, of course, there are no global powers that can exploit an opening, and there are no openings likely to appear. That means that the relationship between the two countries will remain stable, with Canada increasing its position, as natural gas, concentrated in western Canada, becomes more important. The U.S.-Canadian relationship is of tremendous significance to both countries, with Canada far more vulnerable to the United States than the other way around, simply because of size and options. But as important as it is, it will not be one requiring great attention or decisions on the part of the United States in the next decade.

The American relation with the hemisphere divides into three parts: Brazil, Canada, and Mexico. Brazil is far away and isolated. The United States can shape a long-term strategy of containment, but it is not pressing. Canada is going nowhere. It is Mexico, with its twin problems of migration and drugs, that is the immediate issue for the United States. Outside of the legalization of drugs, which would force down the price, the only solution is to allow the drug wars to burn themselves out, as they inevitably will. Intervention would be disastrous. As for migration, it is a problem now, but as demography shifts, it will be the solution.

The United States has a secure position in the hemisphere. The sign of an empire is its security in its region, with conflicts occurring far away without threat to the homeland. The United States has, on the whole, achieved this.

In the end, the greatest threat in the hemisphere is the one that the Monroe Doctrine foresaw, which is that a major outside power should use the region as a base from which to threaten the United States. That means that the core American strategy should be focused on Eurasia, where such global powers arise, rather than on Latin America: first things first.

Above all else, hemispheric governments must not perceive the United States as meddling in their affairs, a perception that sets in motion anti-American sentiment, which can be troublesome. Of course the United States

will

be engaged in meddling in Latin American affairs, particularly in Argentina. But this must be embedded in an endless discussion of human rights and social progress. In fact, particularly in the case of Argentina, both will be promoted. It is the motive vis-à-vis Brazil that needs to be hidden. But then, all presidents must in all things hide their true motives and vigorously deny the truth when someone recognizes what they are up to.

Historically, the United States has neglected hemispheric issues unless a global power became involved, or the issues directly affected American interests, as circumstances with Mexico did in the nineteenth century. Other than that, Latin America was an arena for commercial relations. That basic scenario will not change in the next decade, save that Brazil must be worked with and long-term plans for containment must, if necessary, be laid.

CHAPTER 12

AFRICA: A PLACE TO LEAVE ALONE

T

he U.S. strategy of maintaining the balance of power between nation-states in every region of the world assumes two things: first, that there are nation-states in the region, and second, that some have enough power to assert themselves. Absent these factors, there is no fabric of regional power to manage. There is also no system for internal stability or coherence. Such is the fate of Africa, a region that can be divided in many ways but as yet is united in none.

Geographically, Africa falls easily into four regions. First, there is North Africa, forming the southern shore of the Mediterranean basin. Second, there is the western shore of the Red Sea and the Gulf of Aden, known as the Horn of Africa. Then there is the region between the Atlantic and the southern Sahara known as West Africa, and finally a large southern region, extending along a line from Gabon to Congo to Kenya to the Cape of Good Hope.

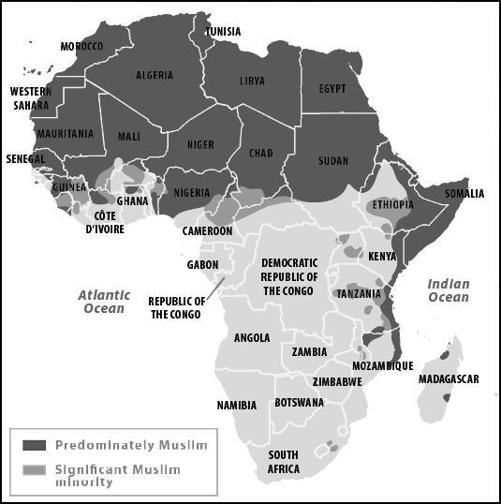

Using the criterion of religion, Africa can be divided into just two parts: Muslim and non-Muslim. Islam dominates North Africa, the northern regions of West Africa, and the west coast of the Indian Ocean basin as far as Tanzania. Islam does not dominate the northern coast of the Atlantic in West Africa, nor has it made major inroads into the southern cone beyond the Indian Ocean coast.

Islam in Africa

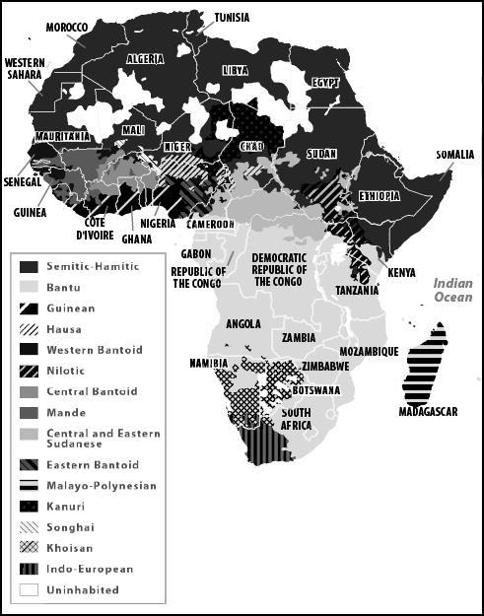

The linguistic map probably gives us the best sense of Africa’s broad regions. But language as a way of looking at Africa is infinitely more complex, because hundreds of languages are widely used and many more are spoken by small groups. Given this linguistic diversity, it is ironic that the common tongue within nations is frequently the language of the imperialists: Arabic, English, French, Spanish, or Portuguese. Even in North Africa, where Arabic lies over everything, there are areas where the European languages of past empires remain an anachronistic residue.

Ethnolinguistic Groups in Africa

A similar irony surrounds what is probably the least meaningful way of trying to make sense of Africa, which is in terms of contemporary borders. Many of these are also holdovers representing the divisions among European empires that have retreated, leaving behind their administrative boundaries. The real African dynamic begins to emerge when we consider that these boundaries not only define states that try to preside over multiple and hostile nations contained within, but often divide nations between two contemporary countries. Thus, while there may be African states, there are—North Africa aside—few nation-states.

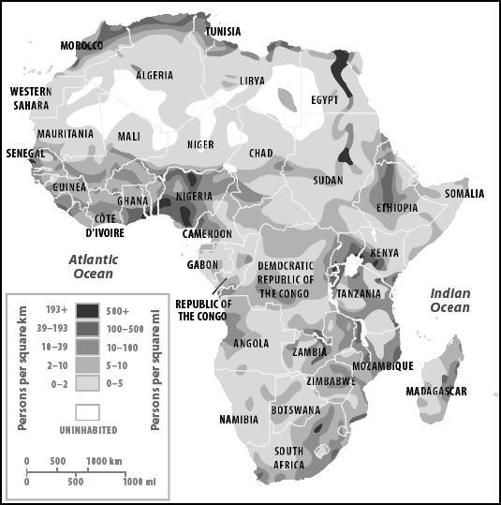

Population Density in Africa

Finally, we can look at Africa in terms of where people live. Africa’s three major population centers are the Nile River basin, Nigeria, and the Great Lakes region of central Africa, including Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya. These may give a sense that Africa is overpopulated, and it is true that given the level of poverty, there may well be too many people trying to extract a living from Africa’s meager economy. But much of the continent is in fact sparsely populated compared to the rest of the world. Africa’s topography of deserts and rain forests makes this inevitable.

Even when we look at these centers of population, we find that the political boundaries and the national boundaries have little to do with each other. Rather than being a foundation for power, then, population density merely increases instability and weakness. Instability occurs when divided populations occupy the same spaces.

Nigeria, for instance, ought to be the major regional power, since it is also a major oil exporter and therefore has the revenues to build power. But for Nigeria the very existence of oil has generated constant internal conflict; the wealth does not go to a central infrastructure of state and businesses but is diverted and dissipated by parochial rivalries. Rather than serving as the foundation of national unity, oil wealth has merely financed chaos based on the cultural, religious, and ethnic differences among Nigeria’s people. This makes Nigeria a state without a nation. To be more precise, it is a state presiding over multiple hostile nations, some of which are divided by state borders. In the same way, the population groupings within Rwanda, Uganda, and Kenya are divided, rather than united, by the national identities assigned to them. At times wars have created uneasy states, as in Angola, but long-term stability is hard to find throughout.