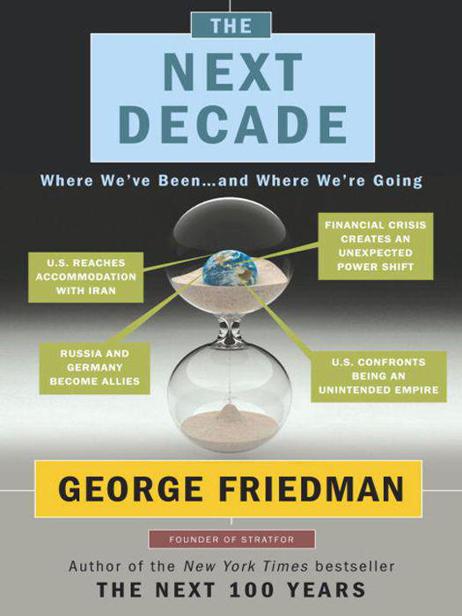

The Next Decade (36 page)

The last decade posed challenges to the United States that it was not prepared for and that it did not manage well. It was, as they say, a learning experience, valuable because the mistakes did not threaten the survival of the United States. But the threat that will arise later in the century will tower over those of the last decade. Look back on the middle of the twentieth century to imagine what might face the United States going forward.

The United States is fortunate to have the next decade in which to make the transition from an obsessive foreign policy to a more balanced and nuanced exercise of power. By this I don’t mean that the goal is to learn to use diplomacy rather than force. Diplomacy has its place, but I am saying that when push comes to shove, the United States must learn to choose its enemies carefully, make certain they can be beaten, and then wage an effective war that causes them to capitulate. It is important not to fight wars that can’t be won and to fight wars in order to win. Fighting wars out of rage is impermissible for a country with such vast power and interests.

The United States has spent sixteen of the past fifty years fighting wars in Asia. After his experience in Korea, Douglas MacArthur, hardly a pacifist, warned Americans to avoid such adventures. The reason was simple: as soon as Americans set foot in Asia, they are vastly outnumbered. The logistical problems of supplying forces thousands of miles from home, and of fighting an enemy that has nowhere to go and is intimately familiar with the terrain, only compound an already overwhelming challenge. Yet the United States continues to wade in, expecting that each time will be different. Of all the lessons of the last decade, this is the most important for the decade to come.

The lesson we should have learned from the British is that there are far more effective, if cynical, ways to manage wars in Asia and Europe. One is by diverting the resources of potential enemies away from the United States and toward a neighbor. Maintaining the balance of power should be as fundamental to American foreign policy as the Bill of Rights is to domestic policy. The United States should enter a war in the Eastern Hemisphere only in the direst of circumstances, when an onerous power threatens to overtake vast territory and no one who can resist is left.

The foundation of American power is the oceans. Domination of the oceans prevents other nations from attacking the United States, permits the United States to intervene when it needs to, and gives the United States control over international trade. The United States need never use that power, but it must deny it to anyone else. Global trade depends on the oceans. Whoever controls the oceans ultimately controls global trade. The balance-of-power strategy is a form of naval warfare, preventing challengers from building forces that can threaten American control of the seas.

The American military is now obsessed with building a force that can fight in the Islamic world. Some say that we have reached a point in which all warfare will be asymmetric. Some describe the future in terms of the “long war,” a conflict that will stretch for generations. If that is true, then the United States has already lost, because there is no way it can pacify more than a billion Muslims.

But I would argue that such an assessment is misguided and that such a goal is a failure of imagination. Generals, as they say, always fight the last war, and it is easy to reach the conclusion while the war is still raging that all wars in the future will look like the one you are fighting now. It must never be forgotten that systemic wars—wars in which the major powers fight to redefine the international system—happen in almost every century. If we count the Cold War and its subwars, then three systemic wars were fought in the twentieth century. It is a virtual certainty that there will be systemic wars in the twenty-first century. It must always be remembered that you can win a dozen minor wars, but if you lose the big one, you lose everything.

American forces might be called on to fight anywhere. It was hard to believe in 2000 that the United States would spend nine of the next ten years fighting a war in Afghanistan, but it has. Shaping a military to keep fighting these wars would be a tremendous mistake, as would deciding that the United States doesn’t want to fight wars any longer and slashing the defense budget.

The first focus must be on the sea. The U.S. Navy is the strategic foundation of the United States, followed closely by U.S. forces in space, because it will be the reconnaissance satellites that will guide anti-ship missiles in the next decade, and shortly after that the missiles themselves will find their way into space. In an age when fielding a new weapons system can take twenty years, the next decade must be the period of intense preparation for whatever may come. The next decade is the time for transition.

The British had the Colonial Office. The Romans had the Proconsul. The United States has a chaotic array of institutions dealing with foreign policy. There are sixteen intelligence services with overlapping responsibilities. The State Department, Defense Department, National Security Council, and national director of intelligence all wind up dealing with the same issues, coordinated only to the extent that the president manages them all. To say there are too many cooks in the kitchen misses the point—and there are too many kitchens serving the same meal. Bureaucratic infighting in Washington may be fodder for comedians, but it can shatter lives around the world. It is easier to leave it as it is, but only easier for Washington. The American foreign policy apparatus simply must be rationalized. The president spends much of his time just trying to control his own team. This must change in the next decade, before things spiral out of control.

Americans like to hold everyone responsible for the problems of the United States but themselves. The problem is said to be Fox News or special interests or the liberal media. At root the problem is that there is no consensus in the United States about whether it has an empire and what to do about it. Americans prefer mutual vilification to facing up to the facts; they prefer arguing about what ought to be to arguing about what is. What I have tried to show is the reality as I see it, in terms of both the regime and the next decade. In arguing that the United States has unintentionally become an empire, I have also made the case that the empire poses a profound threat to the republic. To lose that moral foundation would make the empire pointless.

I have also made the argument for what I call the Machiavellian president, a leader who both understands power and has a moral core. The president is the only practical bulwark for the republic, because he alone is elected by all the people. It is his job to lead so that he can manage, but the president, no matter how crafty, cannot lead alone. He must have the other institutions the founders gave the republic functioning maturely, and, above all, he must have a mature public that takes responsibility for the state of the nation. The New Testament contains this passage: “When I was a child, I talked like a child, I thought like a child, I reasoned like a child. When I became a man, I put childish ways behind me.” The United States has grown up. Its public must too.

Lincoln, Roosevelt, and Reagan all led fractious nations. Each was skillful enough to craft coalitions that were sufficiently strong to get through the storm. But going forward, we need not only clever leaders but also a clever public. A woman asked Benjamin Franklin after the Constitutional Convention about the kind of government the delegates had given the country. “A republic,” he told her, “if you can keep it.”

I genuinely believe that the United States is far more powerful than most people think. Its problems are real but trivial compared to the extent of its power. I am also genuinely frightened, not about America’s survival, but about the ability of the United States to keep the republic provided by the founders. The demands and temptations of empire can easily destroy institutions already besieged by a public that has lost both civility and perspective, and by politicians who cannot lead because they are capable of neither the exercise of power nor the pursuit of moral ends.

Four things are needed. First, a nation that has an unsentimental understanding of the situation it is in. Second, leaders who are prepared to bear the burden of reconciling that reality with American values. Third, presidents who understand power and principles and know the place of each. But above all, what is needed is a mature American public that recognizes what is at stake and how little time there is to develop the culture and institutions needed to manage the republic cast in an imperial role. Without this, nothing else is possible. The situation is far from hopeless, but it requires an enormous act of will for the country to grow up.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Every author of every book is indebted to many people whose thoughts and writings his own rest upon. My more immediate debts are to Rodger Baker, Peter Zeihan, Colin Chapman, Reva Bhalla, Kamran Bokhari, Lauren Goodrich, Eugene Chausovsky, Nate Hughes, Marko Papic, Matt Gertken, Kevin Stech, Emre Dogru, Bayless Parsley, Matt Powers, Jacob Shapiro, and Ira Jamshidi. Each of them helped make this book better than it might have been otherwise. I would also like to thank Ben Sledge and T. J. Lensing for producing the maps—not, I’ve learned, an easy task. My thanks to the Army and Navy Club Library in Washington, D.C., for all its help.

My special thanks to Jim Hornfischer, my literary agent, for his support and encouragement; to my editor at Doubleday, Jason Kaufman, for his unrelenting confidence in me and his always helpful criticism; and to Rob Bloom. Bill Patrick helped turn my turgid prose into much better prose. Susan Copeland kept me on track and organized. I am grateful to everyone at STRATFOR, including our readers, for their lively support and criticism. And, above all, I thank my wife, Meredith, as always, my rock and my guide.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

George Friedman is the founder and CEO of STRATFOR, the world’s leading publisher of global geopolitical intelligence. He is frequently called upon as a media expert and is the author of six books, including the

New York Times

bestseller

The Next 100 Years

, and numerous articles on national security, geopolitics, and the intelligence business. He lives in Austin, Texas.

Table of Contents

I NTRODUCTION: R EBALANCING A MERICA

CHAPTER 1 T HE U NINTENDED E MPIRE

CHAPTER 2 R EPUBLIC, E MPIRE, AND THE M ACHIAVELLIAN P RESIDENT

CHAPTER 3 T HE F INANCIAL C RISIS AND THE R ESURGENT S TATE

CHAPTER 4 F INDING THE B ALANCE OF P OWER

CHAPTER 6 R EDEFINING P OLICY: T HE C ASE OF I SRAEL

CHAPTER 7 S TRATEGIC R EVERSAL: T HE U NITED S TATES, I RAN, AND THE M IDDLE E AST

CHAPTER 8 T HE R ETURN OF R USSIA

CHAPTER 9 E UROPE’S R ETURN TO H ISTORY

CHAPTER 10 F ACING THE W ESTERN P ACIFIC

CHAPTER 11 A S ECURE H EMISPHERE

CHAPTER 12 A FRICA: A P LACE TO L EAVE A LONE

CHAPTER 13 T HE T ECHNOLOGICAL AND D EMOGRAPHIC I MBALANCE