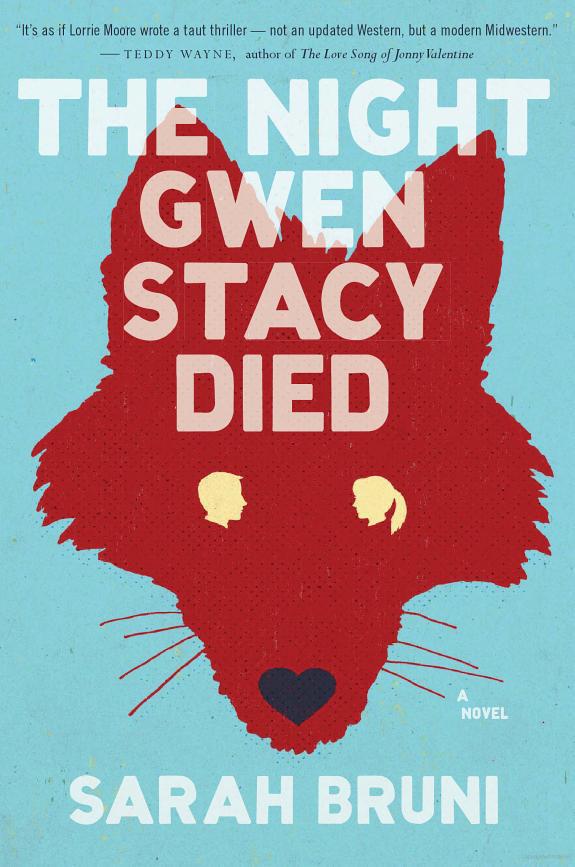

The Night Gwen Stacy Died

Read The Night Gwen Stacy Died Online

Authors: Sarah Bruni

Tags: #Literary, #Coming of Age, #Fiction

Copyright © 2013 by Sarah Bruni

Illustrations by

Sarah Ferone

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to

Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company, 215 Park Avenue South,

New York, New York 10003.

The Library of Congress has cataloged the print edition as follows:

Bruni, Sarah.

The Night Gwen Stacy Died / Sarah Bruni.

pages cm

“A Mariner Original.”

ISBN

978-0-547-89816-2

1. Young women—Psychology—Fiction. 2. Self-realization in women—Fiction. 3. Iowa—Fiction. I.

Title.

PS

3602.

R

848

N

54 2013

813'.6—dc23 2012040352

e

ISBN

978-0-547-89839-1

v1.0713

Spider-Man, Peter Parker, Gwen Stacy, and all other comic book characters named in

this novel were published by Marvel Comics. This novel has not been authorized or

sponsored by Marvel.

For my parents

and for my brothers

SEASONAL CHANGE WAS

descending in its temperamental, plague-like way in fits and spurts on the middle

of the country. There was a false sense to the air, all the wrong smells. That spring,

Sheila bought herself a single-speed bicycle from the outdoor auction along Interstate

80. She rode it down the Coralville strip to work. She pedaled fast, as if to keep

up with traffic—an exercise in futility—and swallowed the air in gulps. When she reached

the Sinclair station, Sheila felt faintly dazed, like someone about to pass out. Sometimes

she saw black spots where the white line of road was supposed to be. “You all right?

Miss?” Motorists would lean their heads out windows when Sheila stopped on the shoulder

of the highway to catch her breath. Or sometimes: “Lady, get out of the road!” This

was Iowa; no one rode bikes along the highway. Bicycling was a nice hobby for children

but not a reliable mode of transportation. For Sheila, this was the most exhilarating

part of the day. This was the only exhilarating part of the day.

It was the spring of the year that coyote sightings started garnering national attention.

The headlines sounded like a string of bad jokes:

COYOTE WALKS INTO A BAR. COYOTE CAUGHT SLEEPING IN MATTRESS SHOP. PACK OF COYOTES

CAUSES DELAYS AT O’HARE

. The scientific community insisted there was nothing to worry about, that the species

was extremely adaptable, that they mostly traveled at night, that they rarely ate

domestic animals without provocation. Yet, people couldn’t help but notice how stealthily

the coyotes seemed to be infiltrating the small towns and cities. Morning joggers

complained of coyotes crouched behind trees along public parks. The presence of the

animals often wasn’t witnessed firsthand by more than a few early risers. But hearing

of such sightings was enough—also knowing they were out there at night, outsmarting

the rats, sleeping in the alleys.

It felt as if entire ecosystems had become confused. That fall, two whales had dragged

their giant bellies onto dry land. The whales seemed determined to beach themselves

despite rescuers’ efforts to return them to the water. Strange symbiotic relationships

were popping up everywhere, often involving the abandoned offspring of one species

adopting an unlikely surrogate parent. A lion cub might choose a lizard as its mother

and receive a five-minute slot on the evening news, curbing coverage of the latest

political corruption scandal or plane crash.

There were other things too. Even in the Midwest, anyone could tell that the whole

planet was out of whack. It had been too warm for snow until well after New Year’s.

The salt-truck drivers were mad as hell. Shovel sales were way down. It was months

later that all that hovering precipitation finally found its way to street level.

March came in like a lion, went out like a lamb being devoured by a coyote. Which

is to say that it warmed up, but in a sneaky, violent way that made everyone slow

to pull out their lighter clothes, so as not to look gullible at a time when everything

felt like a fluke.

You could feel all this in the air, riding to work each day. Sheila was a gas station

attendant, and she was a model employee. Four days a week she biked along the strip,

straight from school to the station. She never missed a shift. She never called in

sick. She was saving up. She had a year’s worth of deposits in the bank—all from working

at the Sinclair station—and when that growing fund hit a certain number, she was leaving

the country for an undetermined length of time. She was buying a plane ticket to Paris,

and anyone who had a problem with that could shove it. “France?” her father said when

Sheila told him her destination. When he said it, the whole country sounded like an

adolescent stunt, a dog in a plaid coat and socks. “Remind me again what’s wrong with

your own country? Are you hearing this?” he’d ask Sheila’s mother, who would shake

her head or shrug. Her sister, Andrea, and her sister’s fiancé, Donny, thought it

was a frivolous way to spend money. They were saving to open a restaurant. Andrea

was watching prices for lots on the west side of town. There was a business plan.

It was going to be called Donny’s Grill.

“But you do all the cooking,” Sheila had protested.

“Yeah, well, it’s a team thing. We’re a team, okay? Teamwork? Does that mean anything

to you?” asked Andrea. “Think about it. Would you eat at a place called Donny and

Andrea’s Grill?”

“No,” said Sheila.

“No, you wouldn’t. And you know why? ’Cause it’s too friggin’ long. Besides,” she

said, “we’re going to try doing all the cooking together.”

Andrea had moved out of the house two years ago, which was about how long she had

been engaged. She started wearing acrylic fingernails so that the hand with her ring

didn’t look so otherwise lonely and unadorned. She favored shades of salmon. As a

girl Andrea had been overweight and eager to fall in love. Sheila wanted, of course,

to fall in love, but not with someone like Donny. Not with someone from Iowa.

Sleeping in her parents’ house, Sheila would sometimes wake to the wheels of jeeps

screeching around the corner. As they turned near the street, several boys would shout,

“Iowa Hawkeye football!” Then, they would make animal noises. The real animals that

lived nearby were quiet, frantic things that made no sounds. Squirrels that scattered

and little sparrows that hopped between the cracks in the sidewalk, scouting out crumbs

with an awkward deference. Most of the animals that had been indigenous to the land

before the college moved in had been preserved in the Iowa Museum of Natural History

on the third floor of Macbride Hall. There, they were stuffed and arranged before

paintings of their natural habitats, interacting with predators, feeding their young.

Several prairie dog pups curled up close beside their sleeping mother; rabbits and

ground birds were positioned as if scurrying at the feet of an elk. A single coyote

in a large case did nothing but stare straight ahead, sitting off to the side of the

other animals, as if it were too proud to act alive. The plaque outside its case said,

“Mountain coyote. Genus and species:

Canis latrans lestes

. Indigenous to Nevada and California, the species can be found from the Rocky Mountains

westward, as far north as British Columbia and as far south as Arizona and New Mexico

.”

The coyote, the sign explained, takes its name from the Spanish word

coyote

—

coyote

from

coyote!

This redundancy struck Sheila as hilarious—but the scientific name was derived from

the Latin: barking dog. Coyotes were wilder, noisier cousins of dogs: kept later hours,

spanned greater territories. Their hunting was marked by extraordinarily relentless

patience. Coyotes were stubborn, though also oddly adaptable. Their communication,

described as howls and yips, was most often heard in the spring, but also in the fall,

the time of year when young pups leave their families to establish new territories. “You idiot, you could have gone anywhere,” she wanted to say to the coyote in the

case, “and you came to Iowa?” But the coyote still seemed young; clearly, it either

was the progeny of transients, or it migrated straight to Iowa only to be promptly

shot and stuffed.

The coyote that Sheila visited always regarded her with a look that seemed to say,

Well, it’s just you and me here, isn’t it? We might as well say everything. Sheila

liked how isolated the coyote seemed to be in the middle of its glass case, staring

straight forward as if about to address her, mixed-up in a survival narrative that

had nothing to do with other coyotes, a transplant from some other territory. At least

once a week Sheila rode her bike to Macbride Hall, pressed her nose to the smooth

glass of the display case, and spilled her heart out.