The Norm Chronicles (18 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Norm. Fantastic news. A precious time. Do be vigilant. Wise words in the attached HSE guide for new mums. See especially …

– lifting/carrying of heavy loads,

– standing or sitting for long lengths of time,

– exposure to infectious diseases,

– work-related stress,

– workstations and posture,

Love to all. Take care. Px.

‘The thing with the missus’s caeso,’ said Kelvin in the pub later, ‘was they couldn’t put it all back in, did I tell you? No, not the baby, you berk, the other stuff, hours, at it for hours they were, ’cause the caeso’s the safe one innit, high-tech beep beep beep like bollocks it is, anyway whaddya mean, I said to him in the blue romper suit, you’re not meant to have bits left over, how do you have bits left over it’s not an Ikea cupboard is it, know what I mean? I mean for starters there’s more room afterwards,

comprendez vouz

? How can it

not

fit? Bloody Tesco bag of emptied capacity still no room and still fat and wobblin’ after how does that add up on volume, eh? Bloody Tardis backwards. But two hours, mate, bodge job I reckon. ’nother cigar? Surprised she didn’t leak Guinness, not even as if yer even surplus caeso bits are

useful

or anything not like yer Ikea thingies them … what do you call them … thingies you can’t put caeso bits in a jar in the garage, well you could, but… now, hey, that is what they do, innit, hospitals, cut you to bits and put half of them in a jar, specimens, pickled, come in for an op and half gets Branstoned, that’s the scam, oh-dear-where’s-that-go-can’t-seem-to-ah-well-never-mind-Sir/

Madam-just-pops-them-in-a-jam-jar-shall-we?’ Loses weight mind, good on a diet. More Scratchings? Which bits anyhow, biologolically speaking, you considered that? Curled up well-packed insides I suppose in their defence but wouldn’t fit, nah! You believe that? Bodge job, I reckon, what are the chances Norm ’nother pint? Go on you Zulu warrior skull it!’

MOTHERHOOD

is the most natural thing in the world. Is it also one of the most dangerous? In 2010 around 287,000 women worldwide died giving birth, 1 in every 480, equal to 2,100 MicroMorts.

3

That’s similar to the average dose of acute fatal risk incurred by a British citizen about every six years, condensed, usually, into a matter of hours, as Norm says.

Even so, how useful are those mortality figures? How useful is Norm in a delivery room? That is, how often is the decision to have children – for those who have a choice – a calculation of risk, even though it might be the riskiest thing a woman does, especially in developing countries?

Danger that makes little difference to our decisions is a good example of probability’s real-life limitations. If you think Norm sounds absurd or irrelevant here, it is for a reason. If emotion or compulsion seems more important than data as Norm scrapes around under the instrument trolley, remember that about risk in general.

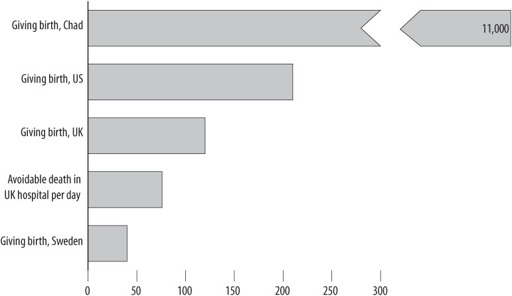

But only up to a point. For the numbers do tell extraordinary stories. They are also the focus of immense effort and concern. In some countries – Chad, Somalia – the risk is five times higher than the global average. Here the maternal death rate in childbirth is a frightening 1 per cent. This risk – 1 in 100 births, or 10,000 MicroMorts – might be considered the natural rate, in that it probably applied in all its brutality for millennia. It is one of the highest risks in this book, although it is eclipsed by some of the unnatural, historical risks somehow contrived by medical authorities. The

natural

rate of death in childbirth is by no means the worst.

For in the developed world, although maternal mortality has improved dramatically, the improvement has been slow, erratic and marked by terrible suffering. As any number of church memorials testifies, even among the upper classes childbirth was dangerous. About 150

years ago, 1 in 200 women still died this way in the UK, many from infection or ‘puerperal fever’.

In charitable laying-in institutions the risk was higher still, worse even than the Stone-Age rate of 1 in 100. Giving birth in this period was safer at home, a fact recognised in 1841. Midwives were rightly feared, but were not nearly so deadly as doctors in some charitable hospitals. In Queen Charlotte’s, London, ‘which possesses a great reputation as a school of obstetric practice’, an extraordinary 4 in every 100 mothers died. Giving birth in Queen Charlotte’s was a risk equivalent to 40,000 MicroMorts, four times as bad as the natural rate of maternal mortality and far more dangerous even than a full year on active service in Afghanistan (around 5,000 MMs in 2011).

4

A hospital could be more treacherous for women giving birth than a modern war zone. And the enemy? Doctors and hospitals killed most of these mothers, not labour itself. If we compare their mortality rate to the natural rate, it implies that three out of four maternal deaths at these institutions were directly caused by medical professionals more deadly than the Taliban.

In Vienna in 1848, a Hungarian doctor, Ignaz Semmelweis, was an exception. He compared two clinics, one for training medical students and one run by midwives. The medical students had two or three times the midwives’ rate of maternal mortality, averaging about 10 per cent, ten times the Stone-Age rate.

In one month, December 1842, Semmelweis reported 75 deaths from 239 births, for a truly incredible rate of almost one in three mothers dying during or after childbirth. The hospital was a slaughterhouse.

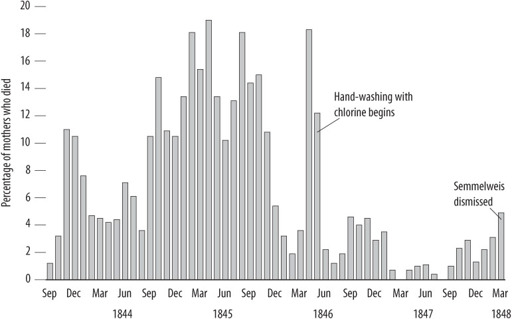

Eventually, he found out that the students – and their professors – went from handling corpses in autopsies to examining women in labour without thinking to wash their hands. He concluded that they were carrying ‘cadaverous particles’ and that it would be safer to give birth in the streets. Some women preferred to do just that if they went into labour on the day of a student clinic. Semmelweis instituted hand-washing with chlorine. The death rate dropped in one month from 18 per cent to 2 per cent.

But his genius proved unhealthy. He was dismissed, moved to Pest, ever more disturbed by the general dismissal of his opinions, and wrote

offensive letters to major obstetricians throughout Europe calling them murderers, with some justification. His behaviour became more erratic and embarrassing and in 1865 he was lured to an asylum, where he died two weeks later – by cruel coincidence from an infection after a beating from his guards. He was 47. It took another 30 years and thousands of unnecessary deaths for the germ theory to become established and Semmelweis to be vindicated.

Figure 15:

Monthly mortality rates at Vienna General Hospital maternity clinic, 1841–9

5

And in the developed world today? According to the Office of National Statistics, each year in England and Wales around 50 women are registered as having died due to giving birth – around one a week.

6

The Confidential Enquiry into Maternal Deaths, published every three years since 1952 and now broadened into the Confidential Enquiry into Maternal and Child Health,

7

says that the true figure is higher – around double if we include deaths both directly due to the birth, such as from blood loss, and also indirect deaths, in which the birth made an existing problem worse.

*

The Confidential Enquiry also found that around 150 children a year

in the UK are left motherless as a result of death from childbirth. The most common direct cause is still infection, as in Victorian times, but this now causes only 5 to 10 deaths a year in more than 700,000 maternities. The most common indirect cause is heart disease, with around 15–20 deaths a year: the stresses of pregnancy on a woman who had heart disease as a child has even featured as a storyline in the BBC radio series

The Archers

.

The UN reports 92 maternal deaths a year in the UK, to give an overall maternal mortality rate of around 1 in 9,000. By historical standards that is extraordinarily good, but still equal to about 120 MicroMorts – roughly the same as a motor-bike ride from London to Edinburgh and back.

Unlike in most other countries, in the UK the risk of childbirth has not fallen in the last 20 years. There is also, still, a strong social class gradient, with five times the risk in lower compared with professional classes. Older mothers are also at higher risk.

Taking the official UN data used for international comparisons, in Sweden the risk is only 40 MicroMorts, a third of that in the UK. As Semmelweis showed, cleanliness matters, and if you accompanied your wife as she gave birth in the US you would have to wear a gown, whereas in the UK you can wander in from the garden. Even so, the official maternal mortality rate in the US of 210 MicroMorts – more than five times that of Sweden – puts it level with Iran in the international league table.

9

Although, inevitably, these figures are disputed.

The American comedian Joan Rivers said that for her the ideal birth would be if they ‘knock me out with the first pain, and wake me up when the hairdresser arrives’, which is essentially what happened in Germany at the start of the 20th century with a form of anaesthesia known as ‘twilight sleep’. Women could not even remember the birth. Anaesthesia had been popularised by Queen Victoria in the 1850s – before which time women had no choice but to suffer Eve’s punishment, as described in Genesis: ‘In sorrow thou shalt bring forth children.’

The fear of giving birth is called tokophobia. In the UK there is an organisation called the Birth Trauma Association, which says that anxiety is widespread and phobia not unusual, although in the extreme case

of phobia this seems to be expressed in terms of disgust as well as concern about safety.

Figure 16:

Average MicroMorts for women giving birth

That they think it worth trying to overcome even this degree of fear shows how childbirth, in particular, presents a difficulty for any simple calculation of harm, namely: what’s it worth? Because there is also, obviously, a benefit, a baby. The fact that millions of women and men accept the risks even if they have access to contraception and no qualms about using it (although see

Chapter 8

, on sex) shows that even severe risks of harm might be worth it.

In fact, there’s evidence that people lower their estimation of the risk the more benefit they expect. This means not simply that for some people the benefit outweighs the risk and for others it doesn’t, but that those who think the benefits are large also tend to think that the risk is

objectively

lower for themselves and everyone else. An imperfect rule of thumb might be: the more you expect, the less you worry. But why should the good reduce the bad? Compensate for, yes, but reduce? The psychologist of risk Paul Slovic calls this the ‘affect heuristic’. If you like an idea, you find it harder to see how it might hurt you.

Would it be safer to press for a caesarean section, as Kelvin’s wife did? It is almost certainly a myth that Julius Caesar was born by caesarean, since it was then only used when the mother was dead or dying, and

Caesar’s mother seems to have been still alive when he was grown up. The first woman to survive a caesarean was said to be a 16th-century wife of a man skilled in neutering sows, which supposedly gave him intimate anatomical knowledge. Regardless of the myth, Caesar’s descendants are enthusiastic about the practice, since now nearly half of births in Rome are by caesarean, rising to 80 per cent in private clinics. At 170 MicroMorts

10

the official record of deaths during caesarean section appears to suggest that a caesarean roughly increases the risk by a half. But the risks are hotly contested, particularly as it is difficult to separate the risks of the operation itself from the risks associated with the reasons for having a caesarean in the first place.