The Norm Chronicles (34 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Kate helps up yrs truly again.

Amazing coincidence … Emily shows up.

Kate arms round yrs truly while yrs truly cleavage close-up. Hi Em.

Em not Hi. Em grabs Kate stiletto, smashes Kate.

Claret.

Em and Kate wrestle on floor. Looks nice. Have idea.

Em bites Kate. Forget idea. Must help. Kick Em.

Kate says no one kicks a woman, which is tech incorrect as just have.

Kate smashes yrs truly on head with stiletto. Em smashes yrs truly on head with stiletto.

Claret.

Kate, Em leave together. Spit on yrs truly.

Lie in blood/saliva-mix to contemplate strange course of events. In consideration of deterioration in relationship and recent facial disfigurement, decide shag option – fresco/other – off.

Stand up v. slow. Go to pub also v. slow. Note unusual coincidence of two limps. Note v. hard to limp with two limps.

Amazing … resident pub dodgy geezer offers sale of cash card and mobile. Reluctantly decide to buy back own mobile.

No dosh.

WHICH OF OUR VICTIMS

is more typical: Prudence, elderly, alone and anxious, or K2, young, drunk and stupid? Certainly Prudence feels at more risk in her own home than K2 feels, staggering around town late at night. While she’s jumpy behind locked doors, he feels indestructible. Reflect on your own impressions of their relative risks and how they’re formed, and we’ll come to the answer in a moment.

Meanwhile, here are two ways that you might take the measure of crime: 1) examine the numbers; or 2) read crime stories in the newspapers.

The numbers are imperfect and hard to interpret. Stories, on the other hand, are quick and gripping, full of ‘psychos’, villains, victims and yobs, inner-city no-go areas, trails of blood and vomit from pub to A&E, muggers on trains, sex attackers in shadows, fraudsters cloning cards and conning the old, girl gangs and knife gangs and pushers at the school gates. Asked why they think crime has been rising for the past ten years (when all available data show that it has been flat or tending downwards over the long term), people point to stories in the media.

We need these stories to understand the character of crime. But as with violence against young children in

Chapter 3

, dramatic events distort our sense of probability. Read or watch these news stories, and the measure of moral decline where none can sleep safely etc. is roughly one vile crime against a pensioner or baby, or a riot. A single instance is about all it takes, and we’re going to the dogs.

Although it’s not the least bit funny if you’re a victim.

*

About one person in seven says they have a high-level fear of violent crime,

2

like Prudence, and no wonder.

†

We are highly tuned to scare stories in the news, as news editors well know. Fear sells. We’re also highly tuned to the latest information and the latest shock story more than to old news or long-run trends. And fear is useful, up to a point. It is often good for survival. Unobservant and contented never saved anyone from a tiger.

So maybe we are right to grab at every straw in the wind for clues about how frightened we should be, so that we can take care, again like Prudence. For the same reasons we are also alert to local rumour – ‘Isn’t the one at number 33 some kind of paedo?’

†

– or to a few incidents of the same kind of crime close together – ‘all those knife attacks’ – and we take special notice of personal experience – anything really, that stands out, any alarm large and small to trigger our attention and help us to a quick judgement.

The psychologist Daniel Kahneman describes the brain as a machine for jumping to conclusions, working according to a law of least effort. This is especially true about fear.

4

If there’s something frightening about, it pays not to hang around. Kahneman says this mental habit is a cognitive bias, and crime stories would seem to appeal to it perfectly. Paul Slovic, a colleague of Kahneman’s in the 1970s, also showed that vivid events are recalled not merely more vividly but in the belief that

there are more of them (see also

Chapter 4

). And crime is often vivid.

The power of the single example over the mass of data is well studied. As Slovic says: ‘the identified individual victim, with a face and a name, has no peer.’ The same goes for animals, he says. During an outbreak of foot and mouth disease in the UK, millions of cattle were slaughtered to stop the spread. ‘The disease waned and animal rights activists demanded an end to further killing. The killings continued until a newspaper photo of a cute 12-day-old calf named Phoenix being targeted for slaughter led the government to change its policy.’

But the plural of ‘anecdote’ is not ‘data’, an old statistical saying goes, and the corollary of ‘vivid’ is not ‘likely’. A crime may be devastating for the victim or family, but it’s unlikely to reveal that we’re going to the dogs, or to say much about the overall risk of becoming a victim. This is almost so obvious as to be trivial, and it is well known. But that doesn’t stop a massive online tribute by thousands of people to one dead sparrow, shot for knocking over a line of dominoes in a competition, while the Dutch bird protection agency lamented a lack of interest in saving the whole species.

5

If we would like a slightly more balanced reaction to single vivid stories, perhaps we should aim to make our description of risks so transparent and convincing that it brings ‘immunity to anecdote’. In fact, this has been investigated by psychologists studying people’s preferences for treatments, who found that good clear graphics, using arrays of icons as in

Chapter 4

, could succeed in making people less influenced by stories of wonder cures and ghastly experiences.

6

Particular events and particular people are usually what stories are about (see our definition in the introduction). In fact, it is often said that without a good dose of the particular, stories lack credibility. That is, authenticity in a story often depends on detail – detail that might apply in this instance and no other. Thus defined, detail is a real-world kick in the shins to generality or abstraction. Detail is the handkerchief that Othello gives to Desdemona and Iago uses to implicate her in infidelity. Small, telling, and ‘true to life’, detail is the precise story of her murder. It is a claim on believability. The literary critic James Wood has described the importance to fiction of ‘this-ness’ – or ‘individuating

form’. By ‘thisness’, he says, ‘I mean the moment when Emma Bovary fondles the satin slippers she danced in weeks before at the Great Ball at La Vaubyessad “the soles of which were yellowed with the wax from the dance floor”.’

7

Used well, detail is an assertion, then, of realism.

All of which is perhaps the most fundamental way in which stories, both fictional and anecdotal, differ from the abstraction of probability, which fails at detail because your own unique circumstances make the average risks hard to apply to you, or to any other individual.

On the other hand, probability does tell us truths of a different order. In particular, it points out that ‘individuating form’ can also fail when extrapolated to other people. That’s why it was individuating in the first place. Which is why statistics urges us to learn immunity to anecdote.

These two versions of truth speak a different language, but the problem could also be seen as a simple problem of scale. One version, the truth of the story, gains credibility from being personal and particular; the other, probability, depends on doubting the evidence of a single experience, precisely because it is a single experience, until it is aggregated with everyone else’s. In each case, what makes one true makes the other a snake. Are they irreconcilable?

For one of the most extreme crime anecdotes imaginable, let’s take Dr Harold Shipman. He was what you might call high-risk healthcare, especially if he knocked on your door for a home visit in the early afternoon. Shipman was a serial killer, and as big and vivid a crime story as they come. Reports about named victims filled the media. A handful of chilling cases gave a stark picture of an avuncular-looking man inviting the trust of his patients as he murdered them in their own living-rooms. It was later estimated that he probably killed upwards of 200, mostly elderly, women in good health by injecting them with diamorphine.

But for the rest of us he was not a trend, or indicative of the behaviour of other GPs, or of anything about the general level of crime. Only in Manchester, where all his murders were recorded as having taken place in one year – the year of discovery – did it make much difference to the ordinary ups and downs in the statistics.

Headlines that play on our deeper fears easily mislead. For instance, murderous stranger-danger to our children looms large in public anxieties,

but the risk is half that from children’s own parents and step-parents. Four out of five adult female victims of murder also know their killer.

8

Alcohol-related violence in England has actually been falling in recent years, contrary to a binge of media coverage, which loves a picture of a lad, off his face, with a bottle. He exists, it is true, but the news is not a balanced sample of behaviour (see also

Chapter 25

, on media portrayal of danger).

But what if lots of stories appear at once, as when four men were murdered – all stabbed – in separate incidents in London on one day, 10 July 2008? This is no longer one shock headline. Here the story was all about how knife killings were an epidemic. We’re not talking anecdotes, we’re talking data … aren’t we? Even so, the BBC’s Andy Tighe reported: ‘Four fatal stabbings in one day could be a statistical freak.’

9

Could it?

*

Every murder is an individual crime that can’t be foretold. But this very randomness means that the overall pattern of murders is in some ways predictable. This sounds uncanny. It is not (see

Chapter 14

, on Chance). It is probability doing what it does brilliantly, at the large scale. DS asked the Home Office how many homicides there had been in London in the past year: 170, they said. So he went away and worked out both how many could be expected up to the current date that year, and the likely pattern of murders over three years, assuming they happened at random. On how many days would there be one murder, two, three or four, and how often there would be none at all? The pattern he predicted turned out to fit the real data almost exactly.

10

He denies consulting a crystal ball. But he does admit to using a little basic probability theory.

†

He did the mathematical equivalent of

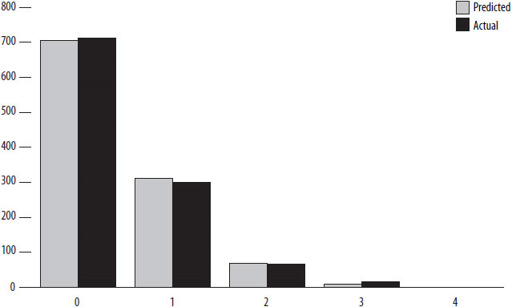

scattering the murders across the calendar like grains of rice, as if they fell randomly. The result is that four murders in one day (four grains of rice on one space) is unusual but not extraordinary, even assuming that the underlying level of violence remains the same. No new or terrifying trend is necessary to produce this result. We would expect it in London around once every three years. We would expect about 705 days with no murders, 310 days with one and about 68 days with two. In fact, the numbers were 713, 299 and 66 – rather close. We can also work out how often we should expect long gaps between murders – a gap of 7 days should occur around 18 times over the 3 years, and it actually occurred 19 times.

Figure 25:

Number of days in which there were 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4 homicides in London, 2004–07

It’s no surprise that stories can be unreliable as measures of risk. What this work shows is less intuitively obvious: that so can sudden clusters of incidents. One story is not a trend, nor necessarily are four of the same stories on the same day. Clusters are in this respect normal and predictable and will occur simply by chance. The alternative – a perfectly regular pattern of killings with an equal number of deaths every week – is absurd. The Home Office has since adopted the same analysis to help it check on changes in the homicide rate, commenting that ‘The

occurrence of these apparent “clusters” is not as surprising as one might anticipate.’

On the train home from a meeting at the Home Office at which DS had said we would expect there to have been about 92 murders in London by that point in the year, he picked up a copy of

The London Paper

, which had the headline ‘London’s Murder Count Reaches 90’.

So we cannot predict individual murders, but we can predict their quantity and their pattern. And by knowing what pattern to expect, we should also be able to spot when something really unusual is happening, when the ups or downs are bigger than chance alone would suggest. When does the pattern of local burglaries look like chance, and when does it look like a new gang on the block? Four murders in London on one day wasn’t a surprise, but interestingly four murders all by the same method – stabbing – probably was. Similarly, the pattern of Shipman’s killings told us little about the underlying risk of being murdered in the population as a whole, but with better data at the time we might have been able to spot in that pattern the hugely heightened risk that Shipman was a multiple murderer.