The Norm Chronicles (35 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Is

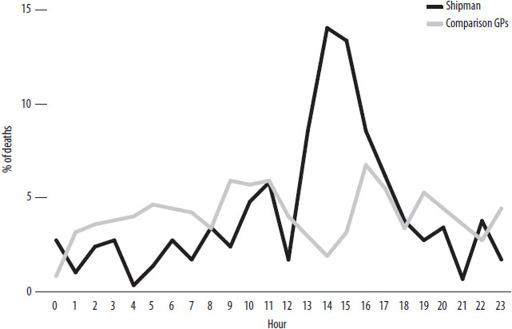

Figure 26

the most chilling graph ever? It shows the time of day at which people die, and how those in Shipman’s care compared with those cared for by other GPs. Shipman’s patients had an improbable habit of dying in the middle of his afternoon visiting hours. Patterns are instructive, if we know what to expect.

And while detectives examining one death at a time struggled to decide if that particular death was murder, statisticians could use data to discover both the scale of Shipman’s murderousness and to tell us where to look for it. And the genius of their investigation was in the simplicity of a question that seeks out patterns among the patients (and the abnormalities in those patterns) by asking, almost trivially: ‘I wonder what time they died?’ The ‘thisness’ of the time of one death in the story of one patient would tell us little in this instance. In aggregate, ‘time of death’ is revelatory. The ‘thisness’ of Shipman’s behaviour, the particulars of his

modus operandi

– the knock on the door for an afternoon visit to an elderly but often reasonably healthy woman – combined with the numbers for him and for others, enable statisticians to deduce far more

than the detectives could.

Figure 26

has a powerful effect on anyone we show it to. The data reveals a truth that particular stories usually miss, because the truth here is contained in the pattern of repetition in many stories, not in just one of them.

Figure 26:

Percentage of deaths registered as occurring at different times of the day or night for Harold Shipman and comparison GPs in the area

Now that we know the need to be cautious about shocking but isolated crime stories, and to understand the kind of patterns that occur by chance so that we also know when a pattern is meaningful, let’s take a step further and focus on the overall numbers. If these are up, that must mean something.

Which it does, provided the ‘up’ has been long enough and big enough. Otherwise, it is liable to the same problem as clusters. The number of crimes goes up and down anyway, by chance, especially in the British Crime Survey, which is based on a sample that will only approximately reflect what’s really going on. No new pattern of criminal behaviour, no moral decline or moral revival is necessary for a certain amount of up and down. ‘Up’ might be chance. ‘Down’ might be an aberration.

A huge amount of media and political energy goes into short-term

changes in the crime figures. If discovering trends is what they’re after, they are usually wasting their time. Burglaries up 5 per cent this year … violent crime down 3 per cent and so on. These seldom tell us anything that couldn’t be explained by chance or changing fashions of reporting. Burglaries since 2005, for example, have gone up or down every year, but not by enough to say anything other than that they have been broadly flat. Whereas vehicle-related theft has fallen every year, and probably really has fallen quite a lot. Only over the longer term are real changes in crime usually apparent.

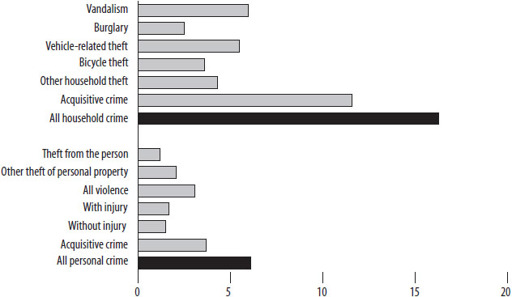

Figure 27:

Average number of victims per 100 people attacked (or average percentage chance of being a victim once or more): England and Wales

Source: British Crime Survey, quarterly update to September 2011

Ups and downs also tell us little about the risk of being a victim. ‘Up 5 per cent’, but from what? There’s abundant psychological evidence that people are more sensitive to change than to base levels of risk. Thirty miles an hour can seem fast or slow depending what you were doing a few seconds ago. It’s the change that we notice more than the absolute level. As for change in crime, the overall figures for 2011 were as low as they’d been for 30 years. The trends in both recorded crime and the Crime Survey have been down or flat since the mid-1990s.

All this deals with changes in impressions of crime, or changes in

the numbers, but it doesn’t tell us what those numbers actually are. So finally, what about that underlying, base-level risk of crime?

Using data, a lot of data, rather than anecdote or a cluster of incidents, we can work out the risk of crime simply by taking the number of victims and dividing it by the number of people. And about 3 in 100 people had their home burgled in 2011, about 3 or 4 in 100 suffered violence, but note that the definition of violent crime contains a wide range of offences, from minor assaults such as pushing and shoving that result in no physical harm through to serious incidents of wounding and murder. Around a half of violent incidents identified by both the BCS and police statistics involve no injury to the victim.

Some people experience more than one type of crime, sometimes more than once. Altogether, the chance for the average individual of being a victim of crime in 2010–11 was about one in five.

11

Fear of crime is not the least bit statistically absurd.

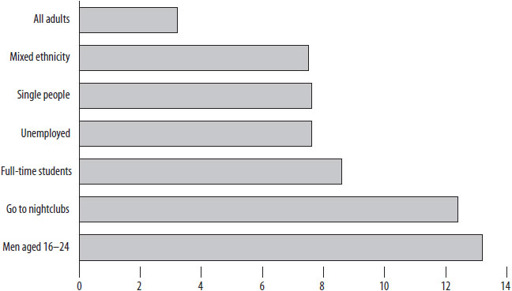

But this is still not that useful. It would have been a fair guide to what might once have happened to Norm, being average, but not for you, or for Norm himself now that he is older. By age 65, the risk of violent crime is less than a tenth of that for a man in his early 20s. So the risk for you depends on who you are and which crime you’re worried about. For example, women are half as likely as men to be victims of violent crime. If you have been a victim before, for many crimes you’re more likely to be a victim again. Ethnicity matters too.

It also matters where you are. Strangely, you were about 16 times more likely to be murdered in Cumbria than in Dyfed Powys in 2010–11, but that turns out to be the cluster problem again. The grim fact underlying the point was that in Cumbria that year the number of homicides went up dramatically when one man, Derrick Bird, shot and killed 12 people. There is always a risk of one-offs, but one-offs do not determine the risk of crime.

A more meaningful geographical pattern is that, if you live in London, you are about twice as likely to be the victim of violent crime as those in Dyfed Powys or Wiltshire. Almost half of the reported robberies in England are in London.

12

Another geographical risk arises with the fact that some types of crime are far more common in poorer areas.

Altogether, a youngish bloke like K2 out and about at night is more representative of crime victims than getting-on-a-bit, middle-class, married Prudence at home in the Basingstoke suburbs in Hampshire. K2’s nightclub habit is surprisingly relevant, although part of the risk associated with it is simply a result of his age. All in all, he is a walking risk factor.

Figure 28:

Risk of violent crime, by group. In 100 people, how many are victims each year

13

For the underlying rate of homicide, if the 172 recorded as committed by Shipman in 2002–3 are excluded, homicide rates peaked in 2001–2, at 15 offences per million people. By 2010–11 the rate had fallen to 12 homicides per million people.

Males – at 16 homicides per million that year – were again more than twice as likely to be victims as females – at 7 per million. That’s 7 MicroMorts per year. Compared with other risks, these numbers are tiny, a small fraction of the average 1 MicroMort

per day

for all external causes of mortality. We adopted the MicroMort partly for its small scale, but on this individual scale the average risk of becoming a victim of homicide is about as close to vanishing as a real risk can be. But would Prudence be reassured?

23

SURGERY

T

HE PATIENT WAS IN A BAD WAY

: white, male, about 85 kg, history of heart disease, complaining of chest pain and shortness of breath.

‘Blood pressure 85 over 60, falling,’ said a nurse. ‘Breathing erratic.’

Pulse? Where was the damn pulse?

There was no time. No time for tests, no time to lose. The brilliant but unorthodox surgeon Kieran Kevlin, 50 years old, silver-haired twin sibling of a famous former professor at the Sorbonne and at the peak of his powers, knew he must operate – at once. Haemorrhage? A valve? His mind raced.

‘Can we save him, doctor?’ breathed Lara, the surgical nurse, as her gloved and skilful hands prepared the patient. A wisp of blonde hair fell across those anxious but still beautiful features beneath the green surgical mask.

‘It’ll be touch and go,’ said Kieran, looking deep into her compassionate blue eyes, his square jaw set with the steely resolve she had long secretly loved. ‘But for his sake, for his family’s sake, for the pride of this hospital and the values we share, let’s give it our best shot.’

From around the operating theatre came murmurs of assent. Kieran was known as a maverick, but also a medical virtuoso, a man who could play ducks and drakes with a battery of surgical techniques before breakfast, and follow it with a ten-mile run.

‘Thank you, doctor,’ said Lara, laying her hand on his gown and sensing the muscular forearm beneath, ‘you might never know how much we all admire your… your …’

‘No, no, thank

you

, Lara. I appreciate your always beautiful thoughts. But there’s no time for that now. We have a life to save.’

And although he knew the gravity of the crisis, this was also a moment he lived for: the moment of decision and incision, the test of self-belief. To put a knife into human skin, deeply aware of his own fallibility, naturally, and of all that could go wrong by ill-luck or bad judgement, but counterbalanced by training to perfection, even if he did say so himself, which luckily combined in his case with natural genius. He was born to be a saviour of broken bodies, an artist revelling in his craft, a musician transcendent in his calling, primed to wound that tender flesh with a razor-sharp instrument, to make that first cut and see those delicious, delicate red pearls, to rearrange, carve up, butcher, slash and rip and burn and slice like ripe mango, oh yes, and stitch and restore and make whole and

re-create

a God-given human body – this was life and meaning.

He made the cut, swift and deep, and then glanced at Lara to see her soft and yielding blue eyes still upon him. He felt her faith. He could not let her down. Yet he also knew that it would be a damn near thing. He was on the edge, trusting to instinct. Even so, he smiled that roguish, dimpled smile of his, and winked.

Lara’s heart filled with desperate joy. If only, she thought, if only he were not so good and devoted to his wife and family. But no sooner had the thought come to her than she felt ashamed – and cursed herself for so selfish, so hurtful a dream. It was not to be. It could not be. She would never know happiness, except for the happiness of being with him now, seeing him in his element, saving lives.

When finally Kieran left the patient to a colleague to clean up, trusting to a smooth recovery, and when his hands met Lara’s as they took off their gowns, and they simply stopped, stood and stared into one another’s soul for what seemed like eternity, and shortly afterwards somehow fell into the back of his car in a far corner of the car park, where their first love-making was of a sweet intensity that strangely reminded her of

his surgery, under the skill of his strong hands, so that the very notion of guilt seemed unkind for an act of such brief perfection – extremely brief, actually – and then when, the very next day, he was suspended and (not long after she realised she was pregnant) later sacked and finally struck off the medical register for negligence following the patient’s death for a procedure subsequently condemned as ‘ludicrously ill-judged’ and, to quote the serious incident report in the ensuing litigation, ‘cavalier in its wilful disregard of basic medicine and good sense as if Mr Kieran Kevlin had been more motivated by the daredevil swipe of the scalpel’, it seemed to her as if a brave and glorious bubble had popped.