The Norm Chronicles (39 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

‘You’ll be all right,’ said Dad to Norm. ‘I’ll watch.’

Norm jumped down. It was grey and a bit wet at the bottom of the hole. He hadn’t noticed before, when he was digging. He peered through to the other side and saw that it was grey and wet there too. He knelt down. The tunnel was dark and the roof low. He wanted to be quick like his brother was quick, and he dipped his head and shoulders and crawled, but his bum caught the bridge and for a moment he was stuck and then he backed up fast.

‘Can’t do it.’

‘Go lower.’

Lower would be not flat, but not strong and quick like it was on hands and knees. It would be in between, and that was awkward and bad. It was bad to move his face and stomach closer to the sand, with so much sand on top. He dipped down, lower, and crawled, and bumped, and so he went lower again, deep in the smell of wet sand, further from the light, his hips low and his arms bent, his lips gritty and his face close.

And then his head was through. But his body was still in, with the thick block of sand over him, and he was staring straight at the sand wall of the side of the hole and the turn on this side was awkward, and he bumped the walls, bumped the roof, and he was stuck again and needed to twist, and puffing, something tight, he … around … that way … and was out, and up … and felt something go inside, and cried. So they jumped on it until it fell. Then he felt in his pocket, and it was empty.

Norm woke up. He put on his dressing-gown and went downstairs to check the balance in his savings account and look again at his pension statement. Silly. He knew what it said. Silly, Norm, to feel so put out, so vulnerable, again, still.

AS IMAGES GO

, penniless and in a hole isn’t subtle. But then nor is the kind of fear that takes you, unreasoning, by the throat, or the strange

way that associations form. Nightmares and phobias don’t go away because we tell ourselves not to be silly.

Norm is old. He’s seen some life. He has experience. But his anxiety here goes back a long way, and for him no amount of wisdom or calculation has cured it. This is the doctrine of the searing memory: the deep personal scar on every judgement. When you can still taste the panic in your mouth like sand, what chance the objective calculation of abstract risk?

For Norm, who trusts in logic, this hurts: once again, his mind won’t obey his own orders, all because of one tyrannical moment years ago. Out of proportion? It makes no odds. For decades he has been telling himself to grow up and be reasonable, but little by little Norm has also been learning what it is to be human.

Phobia is an extreme example of the availability bias that we met in

Chapter 4

(on the problem of framing). Availability bias, as we saw, means whatever comes easiest to mind. Everyone is affected by availability bias, although we’ve afflicted poor Norm more than most by giving him a phobia. It sticks in his mind. It comes to mind often. He can’t help it. Sorry, Norm.

Daniel Kahneman argues that there is evidence people can fight availability biases if they are encouraged to ‘think like a statistician’ and work out what it is that might be shaping their opinions. You can do this, he says, by asking questions such as: ‘is our belief that thefts by teenagers are a major problem due to a few recent instances in our neighbourhood?’ Or ‘could it be that I feel no need to get a flu shot because none of my acquaintances got flu last year?’

The phobia haunts him now because he feels his last years are especially vulnerable, afraid of being penniless and powerless. It’s not much of a sunset, but is it true? Or, if he’s typical, will Norm burn the kids’ inheritance on Saga cruises, flush with an index-linked pension and fat on housing equity withdrawal?

What’s certainly true is that people are living longer (see more on this in

Chapter 26

). That should be cause for celebration, except that so many seem to fear they won’t be able to manage, perhaps even that they face misery and poverty. To others, the generations now reaching

retirement have had it all – and seem hell-bent on blowing every penny. Whatever the truth, instead of the blessing of a long life, we talk of the risks and burdens of age – either the burden of enduring it or the burden of paying through the nose so that others can soak up the sun.

So who is right, and which image of retirement is true: the risky one or the indulgent one?

Both, to some extent. There are pensioners who have done well, and there are plenty who have not. Since this chapter is about financial risk and insecurity in retirement and old age, we will concentrate mostly on the have-nots.

Old age historically has not been a time of plenty. It is estimated that in 1900 about 5 per cent of the elderly overall and about 30 per cent of the over-70s were in the workhouse, still operating under the Poor Law of 1834.

1

Lives inside were often harsh by design, to deter the able-bodied, although workhouses did at least provide medical care.

But they were harsh for the infirm too, and it’s less well known that they became a destination for the old. Still more elderly people relied on payments known as ‘outdoor relief’ – small supplements to scraps of work, charity or family help, so that with luck they could remain outside the walls of the ‘pauper bastilles’.

Most elderly people relied on others to some extent. Many were well cared for, but a big minority were not, and ‘the extreme smallness of their means’ was noted by social reformers like Charles Booth and Seebohm Rowntree.

2

Only after the appointment of a royal commission in 1905 was it suggested that deterrent workhouses be reserved for ‘incorrigibles such as drunkards, idlers and tramps’.

3

George Orwell wrote of standing in the queue for ‘the Spike’ with a tramp, ‘a doubled-up, toothless mummy of seventy-five’.

4

With the development of pensions in the 20th century, retired life steadily improved, although women were still disadvantaged, often receiving pensions only through their status as wives or widows. Even so, most commentators agree that retired life became far less grim – with ‘gold-plated’ pensions and voluntary early retirement at the top. Recently, some have argued that it’s about to get worse again and that the next generation of pensioners faces a meaner future.

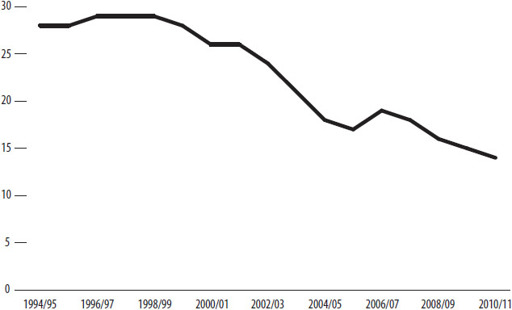

Figure 32:

Percentage of pensioner households living below 60 per cent of the median household income, after housing costs (‘living in poverty’)

5

There are two big fears here: first, not having enough to get by for so long as you can be independent; second, being cleaned out by the cost of care.

So, to the data. About one in every six pensioner households still meets the standard definition of living in poverty – an income below 60 per cent of the median – but this has fallen sharply, by about 45 per cent since 1999. Retirement and old age in relative poverty are still a fact of life for nearly 2 million people in the UK, but it has improved rapidly.

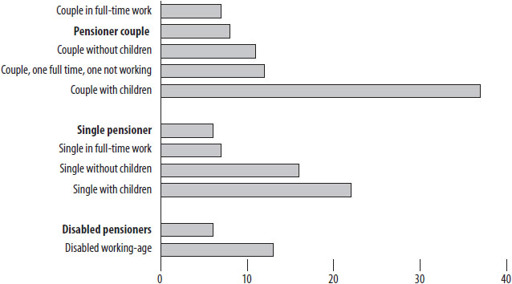

And other groups fare worse. Current pensioners have reached the surprising point where, as a group, they are less likely to be poor, on average, than almost any other section of the population, with almost the only exception being younger people working full-time.

*

Figure 33:

Percentage of different types of household ‘in poverty’

6

Source: Households Below Average Income (HBAI) 1994/95–2010/11

In fact, the very poorest pensioners do better after retirement than before. The English Longitudinal Study of Ageing has followed thousands of people as they grow older. The latest report says that ‘for people with low incomes (less than £150 per week) before retirement, income tends to increase on entering retirement, perhaps as a result of state support for pensioners on low incomes’.

7

So the image of the impoverished pensioner is misleading. Not because some aren’t struggling – they are – but because this is not a characteristic of the way we treat the old. It is a characteristic of the poor – of all ages – and it tends to be less true of the old poor than the younger poor. This makes an important point: most people who are poor in retirement were poor before. Retirement probably didn’t cause it.

For those higher up the income scale, retirement is unlikely to mean poverty, but it’s often a bigger jolt. Incomes here do fall, typically by about a quarter. Net weekly income in about 2009, after taxes and benefits, dropped from an average (Norm again) of a bit less than £400 to just under £300.

Another way of measuring how well off people are is to look at their spending rather than their income. And here huge rises in fuel prices,

for example, have wiped out a chunk of the increased income of the past few years, just as inflation has for other age groups. But since pensioners tend to spend more on basics, such as heating and food, and basics have tended to rise in price faster than inflation generally, pensioners have suffered more from rising prices than others, so the relative improvement in their financial position over time is not as good as it looks.

Even so, overall and in the long term, life in retirement has improved dramatically, especially for the worst-off. Pensioners have become steadily less likely to be classed as poor. For the better-off, retirement does mean a drop in income, but not normally a desperate one.

Yet one cost can change all that. Because although you can insure yourself against unemployment or illness, you can insure against your house burning down or accidents at home, on the road, or abroad, you can insure your pets and in financial markets you can even buy end-of-the-world insurance, you cannot insure against the potential costs of care in old age.

In 2012 this was just about the only potentially expensive lifetime risk that could wipe you out with no way to stop it. There was simply a messy and often inconsistent system that punished the unlucky with the loss of all their assets, including the house. Even at that price, the quality of care varied hugely.

If you can’t insure against a risk, you have no choice but to take the cost on the chin if the worst happens. That can screw up life for everyone, even those who turn out not to need care, because the problem is that you never know if it will be you.

It has been estimated that a quarter of people aged 65 will need to spend very little on care over the rest of their lives. Half can expect care costs of up to £20,000, but 1 in 10 can expect costs of over £100,000. Some could spend hundreds of thousands of pounds, and there is no knowing who, no way of predicting in advance what the costs might be for any one of us.

8

For those who have little or nothing, the state will pay. For the rest, the ruinous tail-end risk frightens them and frightens insurers out of the market altogether.

Uncertainty about who will be in that tail of high need might help explain a puzzle about the behaviour of elderly people: that at a time

when incomes fall for most, and economists expect them to begin to use their savings to help keep up their standard of living, many are still saving hard, perhaps because they fear they will be in the unlucky half. If even that proves optimistic and they are among the unlucky 1 in 10 with more serious needs, saving at this stage of life probably won’t make any meaningful difference. For this reason if no other, Norm is right: life after retirement is still a financial lottery in which some can lose almost everything.

26

THE END

T

HE ASTEROID MISSED

. The odds that it would strike earth had lengthened, as they tend to do following initial discovery, once the trajectory is refined. Even with years to go, it was clear the Apocalypse was postponed, again.

Stargazers watched the fly-by in fascination with a quiet thrill at the thought that this was the one that could have been. ‘What if …,’ they said.