The Norm Chronicles (40 page)

Read The Norm Chronicles Online

Authors: Michael Blastland

Norm stayed inside. And S043 passed quietly about half-way between the Earth’s atmosphere and the moon, then sailed into oblivion. It had all been a false positive. A non-event. House prices rose slightly.

In the evening he stood straight and proud in his pyjamas, a stub of Aquafresh on the toothbrush that hung by his side. He noticed a slouching Norm reflected in a dark window as if his appearance was news to him. He didn’t bother with all that any more.

A minute passed. The stub of toothpaste began to peel off. The pipes of the central heating warmed and stretched.

‘Any pike out there?’ Norm asked out loud, at last.

No answer. He’d asked before but was less sure nowadays that he wanted one. Did it matter – the answer? What if someone told him, and then told him what to do about it, laid out all the answers? Norm sighed. No need for choices if all the answers are given.

He smiled. Then he looked at Norm with narrowed eyes.

‘I see through you,’ he said.

Paler and paler these days, it was almost true. Growing old lent his skin a soft transparency that was not white, nor grey, nor greyish, nor reddish, nor brownish. Tupperware skin, Mrs N said. Tupperware hair too. People ignored him. They said they couldn’t make out what he was saying.

‘Everything all right?’ she called from the other room.

‘Fine,’ he said.

Norm held his own gaze, fixed as a Rembrandt. All his life he had tried to reduce fear to probability. Strangely, he felt no fear now.

‘Probability …? Doesn’t exist,’ he said, just to be rude to the man in the window, who was rude back, sharing one feeble voice. He stared harder, his eyesight so poor these days he could hardly make out …

‘The average of what?’ he mumbled … what with the poor light, feeling almost weightless himself – as the toothbrush dropped.

No pike, then, not for him. He reached down with one hand like the boy who stood – was it on the bank, or was it a dream? – limbs frail and light, and lighter, as he reached, or thought he reached, and felt nothing. Curiously, Norm had disappeared.

Mrs N woke the next morning and rolled over. As she made tea downstairs, Kelvin called about wanting a lift. ‘Have you seen Norm?’ she asked.

‘Who?’ said Kelvin. He was old. But perhaps he was right.

‘Never mind.’

Later, Mrs N noticed his pyjamas, crumpled in the bathroom and a toothbrush on the floor.

Later that day, coming out of the bookies in his wheelchair, Kelvin had a heart attack – all those fags and burgers, probably – and went out suddenly. It was not abnormal for a man of his age and habits, which would have irritated him no end. There’s an average even for unusual people: the unusual-people average, and Kelvin, unknowingly, was typically unusual.

Years later, Prudence had her last coherent thought about Norm as she dribbled into her All-Bran and hoped that, wherever he was, he was safe, but she felt horribly confused by the strangeness of it all and it

wasn’t long before she had forgotten him again. Having looked after herself so well for so long, her body lasted until her mind gave up. She drifted on for five more years or so, happily unaware at last, loved by her family until the end.

On the basis that at least one unusual thing happens to everyone on average, even to the average, it could be argued that Norm’s strange disappearance and presumed death were unsurprising. Except that for some, the unusual thing that happens is that nothing much happens at all.

DID NORM HAVE TO DISAPPEAR

? We’ll answer that in the next, and last, chapter. Though they all had to go somehow. In that respect, death isn’t a risk at all. It has a probability of 1. All that’s risky about it is that the reaper turns up sooner than you think right or proper. For some of us, the right moment can never arrive. For Kelvin death seemed like one more rule, so of course he’d have wanted to rebel. For Pru, when the risk really was creeping right up behind her, just for a change she couldn’t care less. But the timing was, for all of them, in its way normal.

And normal is …?

The 90th Psalm in the King James version of the Bible declares that ‘the days of our years are three-score years and ten’, although up to recently you had to be fairly lucky to reach this use-by date. No English monarch survived until 70 until George III, in 1820, although they did have to cope with draughty castles, bad sanitation and occasional violence. Some historical figures managed it: Augustus Caesar conquered 75, Michelangelo hammered on to the amazing age of 88.

The number 70 was important for another reason: since the ancient Greeks there had been a superstition about the risks of ages that were multiples of 7. In particular, the ‘climacteric years’ of 49 and 63 were thought positively dangerous.

Partly in order to combat this belief, in 1689 a priest in Breslau in Silesia (now Wroclaw in Poland) collected the ages at which people died. The data eventually found their way to Edmond Halley in England, who took time off from discovering comets to construct the first serious life-table in 1693, which uses estimates of the annual risk of dying to work out the chances of living to any age.

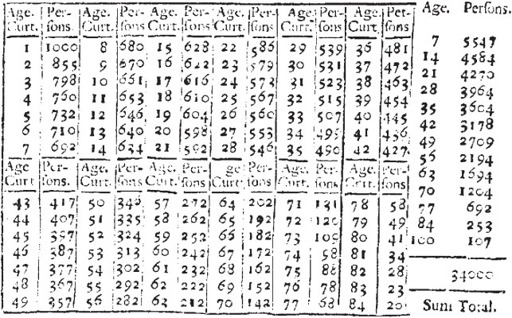

Figure 34:

Halley’s original calculations for what we would expect for 1,000 people starting their first year

1

By year 15 there would be only 628 left alive, of whom 6 would die before 16, a force-of-mortality of 6/628 = 1 per cent. By year 75 there would only be 88 alive, of whom 10 would die before 76, a force-of-mortality of 10/88 = 11 per cent.

He found no evidence of any increased risk at age 49 or 63, so neatly demolished the idea of climacteric years. His comet also duly turned up, as predicted, in 1758, when Halley would have been 101 if the force of mortality had not finally got the better of him. Halley’s life tables only went up to 84: he estimated there was a 2 per cent chance of reaching this age, and just to prove it he died when he was 85, thus by some margin outliving Bill Haley, also of Comet fame, who rocked around the clock only until 55.

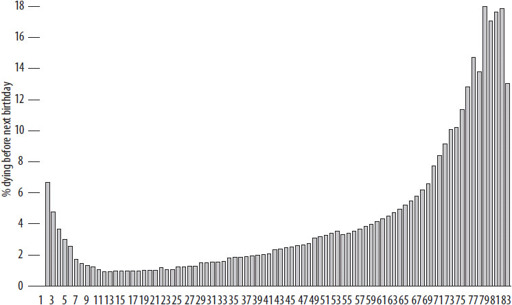

‘Force of mortality’ was, in fact, a technical term for the annual risk of death, now known as the ‘hazard’. The rough shape of the hazard curve – as shown in

Figure 35

– seems to be a constant throughout history, and reflects the ages of man: a high hazard just after birth declines to a point of greatest safety and then starts increasing again, although the precise pattern in childhood and young adulthood depends on the contemporary state of infectious diseases, war and, nowadays, recklessness with drink, drugs and driving.

Figure 35:

The annual risk of death – the ‘force of mortality’ – derived from Halley’s data for the 1680s

About 1 per cent of 15-year-olds are estimated to die each year, and around 11 per cent of 75-year-olds. For UK men in 2010, the corresponding annual risks are around 0.02 per cent and 3.5 per cent.

In 1825 Benjamin Gompertz, barred from university for being Jewish, formulated his ‘law of mortality’, which says that after the mid-20s the annual risk of dying increases at a constant rate. This is extraordinarily accurate, and every year between the ages of 25 and 80 the risk of dying has a relative increase of around 9 per cent, as we already mentioned in

Chapter 17

. Gompertz did his best to fight against his own law but finally died when he was 86.

Longevity is usually summarised by life-expectancy – the average length of life – but averages can be misleading, as we’ve seen so often. Life-expectancy is strongly influenced if there are a lot of deaths in childhood, in which case the survivors may live to a good age, but the average will still be low.

In 1958, when he wrote ‘When I’m 64’, Paul McCartney was only 16, an age when 64 seems old – and particularly in an era when people thought retirement meant putting on your slippers and waiting for death. But even the chance of surviving childhood and reaching 16 has changed dramatically. For example, if we consult that wonderful

resource the Human Mortality Database, we find that back in 1841, a frightening 31 per cent of children born in England and Wales died before they were 16.

2

But if you survived, there was nearly a 50 per cent chance of reaching 64. By the time the Beatles recorded ‘When I’m 64’ for

Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band

in 1966, only 2.5 per cent of children died before 16, and surviving girls had an 85 per cent chance of reaching 64: for boys it was 74 per cent, the difference partly reflecting the unhealthy lifestyles of so many men.

By 2009 less than 1 per cent of children died before 16, and after that the chance of reaching 64 had risen to 92 per cent for women and 87 per cent for men, giving an overall life-expectancy of 82 for women and 78 for men. This does depend crucially on where you live, which is often a function of where you can afford to live: if you are fortunate enough to be a resident of Kensington and Chelsea, then a mostly well-heeled lifetime (though there are pockets of poverty even in K&C) of tea and crumpets, or more likely these days gazpacho and twice-cooked pork belly with an onion & apple velouté, is expected to last until 90 for females and 85 for males, whereas in Glasgow City rather different consumption and material lifestyle is associated with 12 fewer years for females and 13 fewer for males.

3

Although it’s a measure of the speed at which people are putting on extra years of longevity that today’s disadvantaged Glaswegian enjoys the same expected survival as the average man in England did in 1983.

Life-expectancy in the UK has been steadily going up by 3 months a year for decades. That is as if, after using up 48 MicroLives just slogging through a day, you are given 12 back again by those nice people who build drains, give us injections, stop us smoking, sell us low-fat milk and treat us in hospital.

But this is nothing to the extraordinary changes that have occurred elsewhere. In 1970 people in Vietnam had a life-expectancy of 48. It is 75 now, a transition that took England and Wales more than twice as long, from 1894 to 1986.

Behind the cold columns of numbers in historical tables lie powerful events: apart from the world wars, Napoleon’s march on Moscow (which killed 400,000 men) temporarily reduced life-expectancy to

23, the influenza epidemics of 1918–19 took 10 years off life-expectancy for females in France,

4

while AIDS has meant life-expectancy in South Africa declined from 63 in 1990 to 54 in 2010.

5

In 1901 life-expectancy for Black males in the US was 32, with 43 per cent dying before 20, while for White males the corresponding figures were 48 and 24 per cent.

6

After 100 years the gap in life-expectancy was still there, although it had narrowed from 16 years to 5.

All the ‘life-expectancies’ quoted above are based on accumulating the current annual risks of dying – the force of mortality at the moment – and do not take into account any future progress. If we’re going to say something about the prospects for children born now, or yet to be born, we have to make some assumptions about what is going to happen to human health and lifespan. The ‘principal projections’ for England and Wales estimate that males born now, allowing for projected future improvements in health, can

on average

expect to live until 90, and for females it’s 94:

7

32 per cent of males and 39 per cent of females are expected to reach 100 and get a letter from the Queen, or whoever has the job in the early twenty-second century.

8

Babies born in 2050 are projected to live until an average of 97 if male and 99 if female, meaning they will die around 2150. Each generation has an ever-longer reach into the future.

But these projections are, rather understandably, deeply controversial. Is there some inbuilt ageing process, and can it be reversed? Or is there some natural ceiling that we are going to bang our wrinkled, bald heads against? The arguments are fierce. Put a group of specialists on ageing together in a room, and you will be lucky if there are any survivors. People have claimed for years that a ceiling is being reached, and yet life-expectancy just keeps going steadily up. Individual extremes catch attention: Jeanne Calment was born in 1875, soon after the Franco-Prussian War, but kept soldiering on until 1997, when she died at 122, and there are now more verified 115-year-olds than you can shake a walking-stick at.