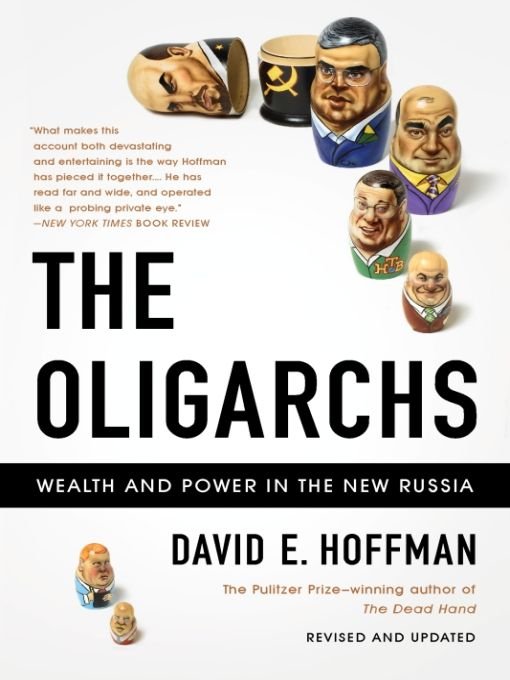

The Oligarchs

Authors: David Hoffman

Table of Contents

Â

Â

Â

Â

Praise for THE OLIGARCHS

“In terms of sheer drama, it's an irresistible tale, and David Hoffman's new book . . . milks it for all it's worth . . . Many future readers will find themselves returning to Hoffman's book to find out what, exactly, makes Russia tick.”

â

Newsweek

Newsweek

Â

“Hoffman brilliantly shows how seemingly halting and insignificant acts finally culminated in changes in a whole society.”

â

Washington Post

Washington Post

Â

“Hoffman makes the tale of the men's rise and fall a masterful blend of adventure and serious, informed analysis.”

â

Foreign Affairs

Foreign Affairs

Â

“[Hoffman] offers one the most wide-ranging and sober of several recent descriptions of the oligarchs during the painful past decade of change in Russia.”

â

Financial Times

Financial Times

Â

“Engagingly written . . . the most comprehensive and most fascinating account of the new Russia to date.”

â

San Jose Mercury News

San Jose Mercury News

Â

“This sad story comes to life in David Hoffman's sprawling new book . . . for those interested in the future of this puzzled and puzzling country, Hoffman's book could not have come at a better time.”

â

Washington Monthly

Washington Monthly

Â

“Hoffman's masterly account of this period . . . dispels any doubts that [the oligarchs] did call the shots . . . Without their efforts the Russian people would still be languishing under a hopelessly ineffective command economy. That is one view. The other is that these men were self-serving opportunists who carried out the biggest heist in history . . .

It is the success of Hoffman's compelling story that we come away convinced of both versions.”

It is the success of Hoffman's compelling story that we come away convinced of both versions.”

â

The London Sunday Times

(Listed in 100 Best Books of the Year)

The London Sunday Times

(Listed in 100 Best Books of the Year)

Â

“Finally, a truly revelatory book about the men who remade Russia in the 1990s . . . experts will be astounded by Hoffman's great reporting, but any curious reader will be intrigued by the stories of these men's extraordinary lives.”

âRobert G. Kaiser

Â

“David Hoffman has produced a monumental book . . .

The Oligarchs

may be the last book ever written on the subject since it is hard to imagine anyone else trying to replicate let alone improve upon the quality of research, analysis, and prose contained in this book.”

The Oligarchs

may be the last book ever written on the subject since it is hard to imagine anyone else trying to replicate let alone improve upon the quality of research, analysis, and prose contained in this book.”

âMichael McFaul

To Carole

The Oligarchs

Ten Years Later An Introduction to the 2011 Paperback Edition

I

N MOSCOW, outside the Khamovnichesky courthouse on the morning of December 27, 2010, a hundred or so people gathered on a snow-covered knoll, dressed against the bitter cold in heavy coats, some of them holding up protest signs bearing a photograph of a man with short-cropped, graying hair and rimless eyeglasses. “Together with the people, for a new Russia!” declared one placard. “To freedom !” said a large campaign-style button.

N MOSCOW, outside the Khamovnichesky courthouse on the morning of December 27, 2010, a hundred or so people gathered on a snow-covered knoll, dressed against the bitter cold in heavy coats, some of them holding up protest signs bearing a photograph of a man with short-cropped, graying hair and rimless eyeglasses. “Together with the people, for a new Russia!” declared one placard. “To freedom !” said a large campaign-style button.

Inside the courtroom, the man in the photograph was standing inside a glass-covered steel cabinet, with a lock and chain on the door. He was Mikhail Khodorkovsky, one of the most ambitious of the first generation of oligarchs who rose to wealth and power after the collapse of the Soviet Union. The day before, at the end of a twenty-two-month trial, Judge Viktor Danilkin had found Khodorkovsky guilty of embezzlement. Khodorkovsky had already spent more than seven years in prison after an earlier trial and conviction of fraud. Now, as the judge, without looking up, read from the lengthy verdict, speaking rapidly and almost inaudibly, Khodorkovsky and his codefendant, Platon Lebedev, listened from inside the glass detention box.

Out on the street, Interior Ministry riot police seized anyone carrying a protest sign on the knoll and dragged them to a waiting bus.

Some of the signs criticized Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, who had ruled Russia with an autocratic hand for a decade. Everyone who held up a sign was arrested. Several of those detained were old women. When one particularly frail woman was arrested, the crowd stirred, chanting “Shame!” and “Freedom!” Some of the protesters went right up to the officers and shouted in their faces. “Do your children know what you're doing here?” said one. “Aren't you ashamed of yourself?” demanded another. The riot police stood by impassively.

Some of the signs criticized Prime Minister Vladimir Putin, who had ruled Russia with an autocratic hand for a decade. Everyone who held up a sign was arrested. Several of those detained were old women. When one particularly frail woman was arrested, the crowd stirred, chanting “Shame!” and “Freedom!” Some of the protesters went right up to the officers and shouted in their faces. “Do your children know what you're doing here?” said one. “Aren't you ashamed of yourself?” demanded another. The riot police stood by impassively.

By 1:00 P.M., about twenty demonstrators had been taken away. The crowd thinned. Vadim Klyuvgant, one of Khodorkovsky's lawyers, came out of the courtroom in a black suit without an overcoat. He said that the judge had not yet pronounced a sentence, but that what had already been read aloud indicated it would be severe. All of the prosecution's charges had stuck, except those for which the statute of limitations had expired. Klyuvgant suggested that the judge was under “strong guidance” from the powers-that-be. He did not say precisely who. He added, “This is a disgrace.”

Two days later, on Thursday, December 31, Danilkin delivered the sentence: Khodorkovsky would have to serve another six years. Khodorkovsky's mother, Marina, bitterly assailed the judge, “Damn you and your descendants!” Through his lawyers, Khodorkovsky released a statement: the verdict showed, he said, that “you cannot count on the courts to protect you from government officials in Russia.”

Leonid Gozman, the head of a small progressive political party with ties to the Kremlin, said, “This is shocking. It was obviously a political, not a judicial decision.”

1

Earlier, a U.S. diplomat who was monitoring the trial had written in a cable to Washington that the “motivation is clearly political.” By holding a trial, the diplomat added, the Russian government was “applying a superficial rule-of-law gloss to a cynical system where political enemies are eliminated with impunity.” The cable was titled, “Rule of Law Lipstick on a Political Pig.”

2

1

Earlier, a U.S. diplomat who was monitoring the trial had written in a cable to Washington that the “motivation is clearly political.” By holding a trial, the diplomat added, the Russian government was “applying a superficial rule-of-law gloss to a cynical system where political enemies are eliminated with impunity.” The cable was titled, “Rule of Law Lipstick on a Political Pig.”

2

Khodorkovsky was taken out of the glass box and returned to prison. It seemed that Putin had succeeded in locking him up and throwing away the key.

But then something unusual happened. On February 14, an Internet news portal based in Moscow,

Gazeta.ru

, and an online video channel, Dozhd TV, carried an interview with Danilkin's assistant, Natalia Vasilyeva, who was also the court press secretary. She said that the judge had started to write his own verdict, but instead was

forced to deliver a different one, given to him by higher authorities. “I know for a fact the verdict was brought from the Moscow City Court,” which oversees Danilkin's court, she said. “Of this I am sure.” The judge was “sort of a bit ashamed of the fact that what he was reading out was not his own, and so he was in a rush to be rid of it.” She added, “I can tell you that the entire judicial community understands very well that this case has been ordered, that this trial has been ordered.”

3

Gazeta.ru

, and an online video channel, Dozhd TV, carried an interview with Danilkin's assistant, Natalia Vasilyeva, who was also the court press secretary. She said that the judge had started to write his own verdict, but instead was

forced to deliver a different one, given to him by higher authorities. “I know for a fact the verdict was brought from the Moscow City Court,” which oversees Danilkin's court, she said. “Of this I am sure.” The judge was “sort of a bit ashamed of the fact that what he was reading out was not his own, and so he was in a rush to be rid of it.” She added, “I can tell you that the entire judicial community understands very well that this case has been ordered, that this trial has been ordered.”

3

The whole spectacle offered a revealing glimpse of the system Putin created to rule Russia. On the surface, all the outward trappings of a market democracy could be found: courts, laws, and trials; stock exchanges, companies, and private property; newspapers, television, radio, and Internet news outlets; candidates, elections, and political parties; and even a few gutsy people to hold up protest signs or whisper truths about the judge. But the real power was in the hands of Putin and his cronies. Their control was not absoluteâit was a soft authoritarianismâbut when they decided to go after someone, as they did with Khodorkovsky, they got their way.

When

The Oligarchs

was written a decade ago, the architects of the new Russia hoped that freedom and competition would drive politics and capitalism. President Boris Yeltsin's reforms gave rise to a people more free and entrepreneurial than any in Russian history. Millions went abroad for the first time, voted in elections, enjoyed a free press, and learned to rely on themselves rather than the state. Anatoly Chubais, who transferred a vast treasure of state-owned factories, mines, and oil fields to private hands, expressed confidence that the new owners, even the greediest tycoons, would be more effective than the old Soviet bosses, simply because they would be forced to compete in a free market that would determine winners and losers.

The Oligarchs

was written a decade ago, the architects of the new Russia hoped that freedom and competition would drive politics and capitalism. President Boris Yeltsin's reforms gave rise to a people more free and entrepreneurial than any in Russian history. Millions went abroad for the first time, voted in elections, enjoyed a free press, and learned to rely on themselves rather than the state. Anatoly Chubais, who transferred a vast treasure of state-owned factories, mines, and oil fields to private hands, expressed confidence that the new owners, even the greediest tycoons, would be more effective than the old Soviet bosses, simply because they would be forced to compete in a free market that would determine winners and losers.

But Yeltsin and his team did not complete the journey they began. Zealous destroyers of the old, they stumbled when it came to erecting the new institutions that Russia desperately needed. Although Yeltsin instinctively understood freedom, he did not grasp the importance of building civil society, the all-important web of connections between the rulers and the ruled. Even more troublesome, Yeltsin fell short in establishing the rule of law to govern the freedoms he unleashed. The result was a warped protocapitalism in which a few hustlers became billionaires and masters of the state. This was the age of the oligarchs, and their story is at the heart of this book.

When Putin took office in 2000, the central problem he faced was what to do with this inheritance. There was no going back to the Soviet Union. But what would follow the tumultuous Yeltsin years? Putin came to the task with little understanding of either Mikhail Gorbachev's

perestroika

or Yeltsin's roaring nineties. Putin, a former KGB agent and backroom operator, had never stood for a competitive election, and he disdained the tycoons. Over the next eight years, he chose a path that was autocratic and statist. He brought to power like-minded men who, loosely, formed their own clan. Called

siloviki

, or the men of the security services, they shared Putin's penchant for control and hoped to enrich themselves in the process.

perestroika

or Yeltsin's roaring nineties. Putin, a former KGB agent and backroom operator, had never stood for a competitive election, and he disdained the tycoons. Over the next eight years, he chose a path that was autocratic and statist. He brought to power like-minded men who, loosely, formed their own clan. Called

siloviki

, or the men of the security services, they shared Putin's penchant for control and hoped to enrich themselves in the process.

Putin, in his first year in office, forced out Vladimir Gusinsky, the media magnate, and soon after, Boris Berezovsky, both prominent oligarchs of the 1990s. Putin spoke of brandishing a club to make the tycoons heel and vowed there would be no such thing as oligarchs as a class. “This is how I see it,” he said. “The state holds a club, which it uses only once. And the blow connects with the head. We have not used the club yet. We have only shown it, and the gesture sufficed to get everyone's attention. If we get angry, however, we will use the club without hesitation.”

4

Putin told the remaining oligarchs from Yeltsin's day that they could keep their assets, but that he would brook no challenge. They fell into line. Unlike Yeltsin in the freewheeling nineties, Putin preferred a system of state or crony capitalism in which the powers-that-be would choose the winners and losers.

4

Putin told the remaining oligarchs from Yeltsin's day that they could keep their assets, but that he would brook no challenge. They fell into line. Unlike Yeltsin in the freewheeling nineties, Putin preferred a system of state or crony capitalism in which the powers-that-be would choose the winners and losers.

Other books

Your Next-Door Neighbor Is a Dragon by Zack Parsons

When the Heart Heals by Ann Shorey

My Neighbor's Will by Lacey Silks

Homeless by Nely Cab

Bad Luck Cadet by Suzie Ivy

Death by Lime: A Key West Culinary Cozy - Book 5 by Summer Prescott

When We Were Us (Keeping Score, #1) by Tawdra Kandle

Plum Deadly by Grant, Ellie

Death Comes for the Fat Man by Reginald Hill

Never Street by Loren D. Estleman