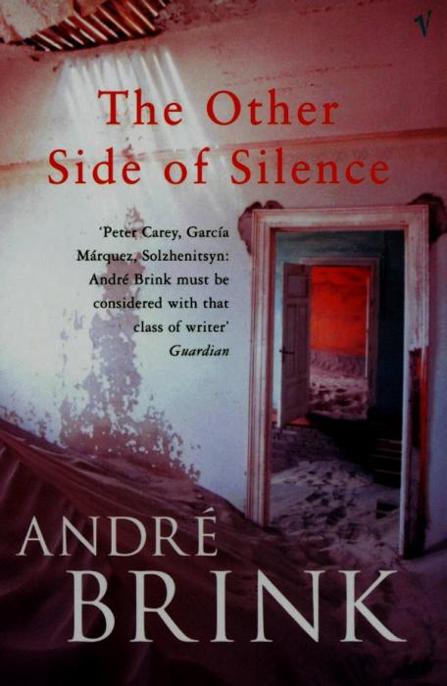

The Other Side of Silence

Read The Other Side of Silence Online

Authors: André Brink

André Brink

The Other Side of Silence

2002, EN

As a small child in a wintry Bremen, Hanna

dreams about the other side of silence, the place where the wind

comes from and palm trees wave in the sun. Seeing her chance to

escape from years of abuse in an orphanage and in service, Hanna

joins one of the shiploads of young women transported in the early

years of the twentieth century to the colony of German South-West

Africa to assuage the needs of the male settlers. Following

atrocious punishment for daring to resist the advances of an army

officer, she arrives in a phantasmagoric refuge in the African

desert – “prison, nunnery, brothel, shithouse, Frauenstein”.

When the drunken excesses of a visiting army detachment threaten

her only companion, Hanna revolts.

Mounting a ragtag army of female and natives, she sets out on an

epic march through the desert to take on the might of the German

Reich. This apocalyptic journey through the darker regions of the

soul will also reveal to her the hidden meanings of suffering,

revenge, companionship, love and compassion.

Table of contents

1

·

2

·

3

·

4

·

5

·

6

·

7

·

8

·

9

·

10

·

11

·

12

·

13

·

14

·

15

·

16

·

17

·

18

·

19

·

20

·

21

·

22

·

23

·

24

·

25

·

26

·

27

·

28

·

29

·

30

·

31

·

32

·

33

·

34

·

35

36

·

37

·

38

·

39

·

40

·

41

·

42

·

43

·

44

·

45

·

46

·

47

·

48

·

49

·

50

·

51

·

52

·

53

·

54

·

55

·

56

·

57

·

58

·

59

·

60

·

61

·

62

·

63

·

64

·

65

·

66

·

67

·

68

·

69

·

70

·

71

·

72

·

73

One

S

he hasn’t always

looked like this. There was a time, there must have been a time,

when the face looking back from the mirror was different.

Diffidence, yes, always. Abjection, fear. Pain, often. Terror,

perhaps. But a difference still – and not only because once her

hair was long and, people said, beautiful, but a difference that

went beyond the obvious, hovering behind the cracked and mottled

surface. She goes on staring, as if she is expecting something else

and something more. Surely blood should leave a stain? She has

washed her hands, of course. Her whole body in fact. Washed and

washed and scrubbed enough to draw new blood from under the skin;

but there may be something else that shows in ways the eyes are

indifferent to. Does death not show? Murder? The ghost stares back,

still inscrutable. And yet there must have been another face, once.

Not a matter of age: even as a child she was old, they used to say.

But that was in the Time Before, and it was another country. There

was greenness there, a green intense enough to darken the eyes,

unlike the hard flat solid light of this land, its hills and

outcrops and dunes, its sky drained of colour, a landscape too old

for memory. The Time Before was green and grey and wet, and it was

permeated by the booming of bells. Here is only silence, a silence

of distance and of space, too deep even for terror, too everywhere,

and marked only, at night, by the scurrilous laughter of jackals,

the forlorn whoops of a stray hyena. Or, more immediately, by the

whimperings and hysterical rantings of the women withdrawn into

their rooms. This is the Time After. Untrodden territory. And no

weapon of attack or defence to face it with, no protection at all.

Only this feral knowledge:

I have not always looked like

this

.

The candle flickers and smokes in an invisible draught; nothing

can keep out the night. This is a special kind of darkness. So

dark, so palpable, it closes in from all sides on the meagre flame.

There is no radiation of light from it at all, just the shape of

the flame, no halo, no hope. As if the surrounding darkness is

rolling in, like a slow wave unfurling, to spill itself into the

small blackness in the heart of the flame; the night outside

reaching inward to the darkness in herself. (From those early days

in the Little Children of Jesus come the voices of the pious women

chanting like crows in the gathering night:

The light shines in

the dark and the dark understands it not

.) So one cannot be

sure of anything one sees. The eyes are tricked as her face

dissolves in the ultimate dark, the dark beyond individuality and

identity, beyond any name.

T

he name was what

first intrigued me. Hanna X. Again and again I worked through the

documents in newspaper offices, contemporary reports, archives, all

those dreary lists, all the names, each as tentative as the title

of a poem, promises withheld. In typescript, shorthand, Gothic

print, copperplate, italics, blotted scrawls. Christa Backmann –

Rosa Fricke – Anna Kochel – Elly Freulich – Paula Plath – Babette

Weber – Use Renard – Margarete Mancke – Frida Scholl – Johanna Koch

– Olga Gessner – Elsa Maier – Dora Deutscher – Helena Hirner –

Charlotte Bockmann – Marie Reissmann – Clara Gebhardt – Martha

Hainbach – Christa Hofstatter – Gertrud Muller – and on and on and

on, without any sense of alphabet or rhyme or reason, in that

interminable shuttle of correspondence between Europe and Africa

(in Berlin, Herr Johann Albrecht, Herzog zu Mecklenburg and his

formidable sidekick Frau Charlotte Sprandel at the Deutsche

Kolonialgesellschaft; in Windhoek, the Kaiserliche Gouverneur von

Deutsch-Südwestafrika) concerning – and deciding – the fate of the

many hundreds of women and girls shipped from Hamburg to the remote

African colony in the years between 1900 and 1914 or thereabouts to

assuage the need of men desperate for matrimony, procreation or an

uncomplicated fuck. Thekla Dressel – Lydia Stillhammer – Josephine

Miller – Hedwig Sohn – Emilie Marschall – names and names and

names, each with its surname and its place of origin – Hannover or

Holleben, Bremen or Berlin, Leutkirch or Lubeck, Stuttgart or

Saarbrücken. Among all of them that solitary first name unattached

to a surname. Hanna X. Town of origin, Bremen. That much was known,

but no more. Later, true, after her arrival at Swakopmund and her

confinement in the secular nunnery of Frauenstein somewhere in the

desert, the name of Hanna X recurs once or twice in the odd

dispatch or letter. In

Afrika Post

it surfaces in connection

with a trial that was to have taken place late in 1906 but was

cancelled before it could come to court, as a result of the suicide

of an army officer, Hauptmann Bohlke, reputedly involved in the

matter. After which, it seems, official intervention very

effectively put a lid on it, no doubt to save the reputation of His

Imperial Majesty’s army. With that, she disappears once again into

silence, still stripped of a surname, still fiercely, pathetically

(or ‘obdurately’, as the report on the aborted trial had it)

silent.

Hanna X.

Initially, it seems, the mystery might have been caused quite

simply by a blotted scrawl in one of the lists compiled by Frau

Charlotte Sprandel’s secretary which her correspondents, either

unable or too hurried and harried to decipher, replaced with the

provisional, convenient, all-purpose X. And after that, most

likely, no one could be bothered. Why should they be? What’s in a

name?

When nearly a century later I went to Bremen myself in a

last-ditch attempt to return to sources, it only too predictably

brought me up against the blank of the War. Almost nothing had

survived that destruction: no records, no registers, no letters;

and it was too late for the memories of survivors. I had no date of

birth, no names of parents, to go by. At the time of her passage to

Africa on the

Hans Woermann

in January 1902 she might have

been twenty, or twenty-five, or even thirty (presumably not older,

as one of the prerequisites for selection was to be of

child-bearing age in order to be of use to the Colony); even if

there had been town and district records left since 1875 or

thereabouts, where would I start without a surname to guide me? As

in practically all the other towns I’d visited whole blocks bore

the sobering legend,

1945 Total zerstört. Wiederaufbau 1949

.

But if buildings could be rebuilt or restored, this did not apply

to printed records. Gone, all gone: census details, public

accounts, lists of domicile, registers of births or marriages,

particulars about the inmates of orphanages or poorhouses, even of

brothels. Here was, had been, no Hanna X. Or, perhaps, too many.

Total zerstort

.

Maybe it was my disappointment with my wild-goose chase which on

that rainy morning during my visit to Bremen had made me

particularly receptive to the paintings of Paula Modersohn-Becker

in the Roselius Collection: those glimpses of humanity, of

femininity, those solitary and deprived figures, images of almost

terrifying isolation, and yet of defiance, a universe of melancholy

and understatement and muted colours behind which one sensed a

forever unexpressed secret world the onlooker could only guess at,

never gain access to. Suggesting, it seemed to me, the male

spectator, the heart of being woman, the pathos of being

irredeemably young, or irredeemably old, two stages of femininity

here remarkably collapsed into each other.

I can recall, from that visit to Germany, only one other

painting that marked me so deeply: a large canvas in the Neue

Pinakothek in Munich called

Feierabend

by an artist whose

name I jotted down on a piece of paper and have since lost. A very

young girl seated at a kitchen table with a middle-aged peasant

suitor who has his back turned to the observer. One large blunt paw

rests on her thigh. His whole body, his ill-fitting jacket, the

back of his narrow head, everything defines him as a loser – a

mean-spirited, violent, hard-drinking, abusive loser. She, too, is

evidently poor. But she is young, her thin body can barely contain

the rage and resentment that seethe in her against this moment

which will decide the rest of her life. In the debilitating

knowledge that he is the very last man she wants, yet the only one

she may ever be allowed to lay claim to.

Behind the gallery in Bremen where I spent the whole morning,

Modersohn-Becker’s melancholy drawn across my shoulders like a

threadbare blanket, lies the Rathausplatz with its post-war

sculpture representing the Musicians of Bremen – the decrepit old

Rocinante of a horse, the mangy dog, the scraggy cat, the

dilapidated rooster from the Grimms’ tale, their cacophony

eternally petrified; but one could still imagine, turning away from

the square, with what hellish abandon, given half a chance on a

winter’s night, they might once again break into braying and

barking and mewing and cockadoodledooing to blast the fear of

everlasting damnation into robbers and honest burghers alike.

From the Plate, too, came, at night – and that has become for me

the defining memory of Bremen – the sound of bells invading the

entire Hotel Uebersee in which I was lodged. It would continue for

minutes on end, feeling like hours, a summoning of uneasy minds to

heaven or to hell. Bells obviously of various shapes and sizes, at

least one of which, judging from the sound, must be enormous,

reverberating with a deep, unearthly boom that conjured up the

image of a giant sculptor giving form and dimension to chaos,

creating from it an entire town and its people and its dark

history, ringing and ringing through all the centuries of crawling,

teeming human life, and hope, and despair, and suffering, and

suffering, and suffering.

From this Bremen, from this sound, from the memory of those

throwaway musicians, came Hanna X. Into a life marked by her own

several deaths. The first of these must have occurred even before

she was dumped, more dead than alive, on the doorstep of the Little

Children of Jesus on the Hutfilterstrasse. And then twice during

the years in the orphanage. Once, we do know, on the

Hans

Woermann

ploughing through darker than wine-dark seas on its

way from Hamburg, past Madeira, and Tenerife, and Grand Bassa, down

the coast of Africa. And then, of course, any number of times in

German South-West Africa, now Namibia. Each of these the shedding

of an old skin, a death, a new beginning, like a menstrual cycle. A

little mourning, a little celebration. Life does go on. And each of

these might be the starting point of a story; each, like the sound

of the giant bell in Bremen, the shaping of a person, of people, of

memories, of a history.