The Oxford History of the Biblical World (10 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

The Mari tablets, along with other sources, allow us to sketch the political history of Syria and Mesopotamia in the early centuries of the second millennium

BCE

. The written sources are particularly helpful in illuminating the rise of Shamshi-Adad and the collapse of his empire following his death, in tracing developments at Mari before, during, and after Shamshi-Adad’s reign, and in chronicling Hammurapi’s slow rise to dominance over Mesopotamia.

The early years of Shamshi-Adad’s long career as king are known only from a text called the

Mari Eponym Chronicle,

first published in 1985. The

Chronicle

lists the names of the years of Shamshi-Adad’s reign, along with brief notes of important events that occurred in each year. From it we know that he became king as a youth. The original seat of his kingdom is not known, and his true rise to power took place only after he had occupied his throne for approximately twenty years. In his twenty-first regnal year, he conquered the city of Ekallatum, just north of Ashur. There he ruled for three years before overthrowing Erishum, king of Assyria, and seizing his victim’s crown. From the capital city of Ashur, Shamshi-Adad began to expand his empire westward, eastward, and southward, taking over the Habur region and the Balikh River to the west, subduing Mari and other cities to the south, and expanding eastward as far as Shusharra on the Little Zab River. Within a few years he had formed a major empire and become the most powerful king of the region.

Having established his empire, Shamshi-Adad moved his own capital westward to Shekhna, in the land of Apum, changing its name as we have seen to Shubat-Enlil. Excavations since 1979 at Tell Leilan have begun to yield significant information about this city. Several important public buildings from the time of Shamshi-Adad have been excavated, including a large temple located on the acropolis and a palace in the lower city, which has produced about 600 tablets that date from the end of his reign (1781

BCE

) until about 1725. While most of the tablets are administrative texts, approximately 120 are letters to two successors of Shamshi-Adad at Shekhna. In addition, fragments of 5 treaties between kings of Apum and their neighbors have been recovered. In 1991, archaeologists found another substantial administrative building, containing a group of 588 small receipt and disbursement tablets that date from the final years of Shamshi-Adad’s reign. Still awaiting full study, these tablets promise to add much to our knowledge of Upper Mesopotamia during the eighteenth century

BCE

.

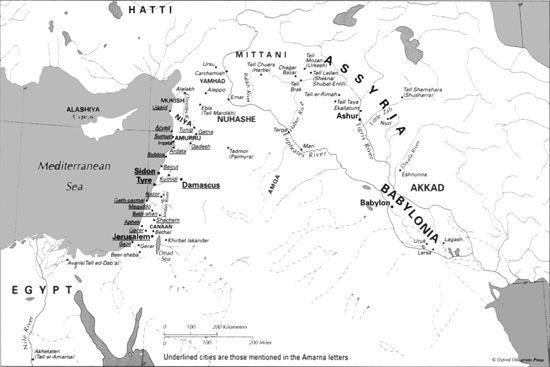

The Near East during the Second Millennium

BCE

By the time he became the ruler of this empire, Shamshi-Adad had two grown sons, whom he appointed subrulers over parts of his realm. The elder son, Ishme-Dagan, resembled his father as an able soldier and administrator. The letters of Shamshi-Adad show the two men’s close relationship and reveal the father’s pride in his son. Ishme-Dagan was appointed ruler of Ekallatum in Assyria to keep control over the eastern part of the empire.

Much to his chagrin, the king’s other son, Yasmah-Adad, proved incompetent and lazy. Shamshi-Adad placed him in charge of Mari, once he had captured that city, hoping that the young man would look after the southern part of the empire. But Shamshi-Adad found himself spending much of his time patching up Yasmah-Adad’s poor handling of his job. The letters between father and son vividly show their strained relationship. “Are you a child and not a man? Have you no beard on your chin?” Shamshi-Adad wrote on one occasion. “While here your brother is victorious,” he scolded another time, “down there you lie about among the women!” A letter survives in which Yasmah-Adad defended himself against one of his father’s barbs, arguing that his subordinates must have been lying about him to his father.

The archives at Mari, as well as smaller ones from Tell Shemshara (Shusharra) and Tell er-Rimah, show Shamshi-Adad as an energetic administrator, constantly moving about his empire and involving himself in all the important—and many of the unimportant—decisions made in the cities that he ruled. It is a tribute to his personal abilities that he held his empire together so well.

Shamshi-Adad ruled for thirty-two years after his conquest of the city of Ashur. His empire, however, did not survive his death. Once he died, the city-states Eshnunna in the southeast and Yamhad to the west immediately began reestablishing their influence in the region. Ishme-Dagan maintained control of Assyria for a while, but he had to surrender the rest of the empire. Yasmah-Adad was overthrown in Mari within four years of Shamshi-Adad’s death, and the previous dynasty returned, Zimri-Lim assuming the throne.

Most tablets from Mari come from the reign of Zimri-Lim. From them we not only learn many details about this king and his domain, but also gain important background information about his family, whom Shamshi-Adad had forced from the throne of Mari. This information explains much about Zimri-Lim’s actions as king.

About the time of Shamshi-Adad’s rise to power in Assyria, Mari was ruled by Yahdun-Lim, a member of the Simal (northern) branch of the Hanean tribal confederation. Inscriptions that survive from his reign depict him as a potent rival to Shamshi-Adad. But eventually Yahdun-Lim suffered a serious defeat in battle and

was apparently assassinated by a member of Mari’s royal court, Sumu-yamam, who may in fact have been Yahdun-Lim’s son. Within two years Sumu-yamam himself fell victim to a palace coup. Shamshi-Adad thereupon saw his chance to expand southward and incorporate an important rival into his kingdom. Capturing Mari, he placed his son Yasmah-Adad on the throne.

The young Zimri-Lim, apparently either Yahdun-Lim’s son or nephew, had fled Mari before Shamshi-Adad’s conquest of the city and found asylum in Aleppo, the capital of Yamhad. Sumu-epuh, the king of Yamhad and Shamshi-Adad’s most significant rival, presumably considered that offering support to Zimri-Lim as the legitimate heir to Mari’s throne might give him valuable leverage against Shamshi-Adad.

After Shamshi-Adad’s death, Zimri-Lim returned to Mari and regained his family’s throne. In this he got substantial support from Yarim-Lim, Sumu-epuh’s successor in Aleppo. Zimri-Lim not only came to dominate the land around Mari, but he also brought all of the middle Euphrates and the Habur River Valley under his sway and opened extensive trade relations throughout the Near East. He maintained good relations with Yamhad, marrying Yarim-Lim’s daughter, Shiptu, early in his reign. But he also cultivated cordial relations with Babylon to the south and with Qatna to the west.

The correspondence of Zimri-Lim shows that he followed Shamshi-Adad’s example in maintaining close contact with his governors, vassals, and officials. A wide variety of issues filled the letters dispatched to the palace at Mari. Messages from various governors kept him informed about the political situation throughout his realm. His ambassadors to other states sent regular reports. Numerous letters concerned relations between the government and the pastoral nomads who migrated through the middle Euphrates and the Habur region. Reports from members of his palace staff and his family also found their way into the archive, as did letters from religious personnel, often reporting omens, prophecies, or unusual dreams that seemed to affect the king.

Zimri-Lim’s correspondence makes possible a partial account of his reign. Soon after assuming the throne he violently suppressed a rebellion among the Yaminite tribes, the southern members of the Hanean tribal confederation, who apparently saw no benefit in supporting a restoration of the Yahdun-Lim line at Mari, which belonged to a northern, Simalite clan. Of all the pastoral nomadic groups in Zimri-Lim’s domains, the Yaminites remained the least cooperative. The tablets also indicate that Eshnunna tried to regain territory in the Habur region that it had controlled prior to Shamshi-Adad’s reign, and they show that Zimri-Lim was deeply involved in opposing this attempt at expansion. We can also watch the slow rise to power of Hammurapi, king of Babylon, who for years remained a faithful ally of Zimri-Lim. But as he gained control of Lower Mesopotamia, Hammurapi suddenly turned on his old friend, overthrew him, and in 1760

BCE

destroyed Mari. Thus abruptly ended its political power.

Following the overthrow of Mari, the middle Euphrates remained only briefly under Babylon’s control. After Hammurapi died, the city of Terqa took Mari’s place as the capital of the region. The land bore the name

Khana

during this time, but we have little information about its economy. Few material remains of the period have

been excavated, and although recent digs at Terqa have produced some tablets, these come largely from private archives.

The most powerful kingdom to the west of the Euphrates was Yamhad, which thwarted the expansive plans not only of Shamshi-Adad but also of Hammurapi. It continued to dominate the north through the seventeenth century. Despite its importance, we know little about Yamhad during the Middle Bronze Age. Excavations at Aleppo, its capital, have uncovered no levels of this period and only one fragmentary inscription (as yet unpublished). We know Yamhad only from outside sources, such as the Mari tablets and a small but helpful archive from an important trade city along the Orontes River called Alalakh, over which ruled members of the royal family of Yamhad for about a century. The Alalakh archive dates to a few decades after the fall of Mari and provides information about the late eighteenth and part of the seventeenth centuries

BCE

.

The Mari letters illuminate the conflict between Shamshi-Adad and Yamhad. The two states were evenly matched, both militarily and politically. Thus Shamshi-Adad astutely formed an alliance with Qatna, the major power south of Yamhad, while the kings of Yamhad allied themselves with Hammurapi of Babylon, who opposed Shamshi-Adad from the southeast. After Shamshi-Adad’s death, Yamhad played a major role in the sundering of his empire, as shown by Yarim-Lim’s success in returning Zimri-Lim to the throne of Mari as a staunch ally of Yamhad.

Hammurapi of Babylon seems not to have attempted to conquer Yamhad, which continued to prosper into the seventeenth century. The Hittites, who rose to power in Anatolia in the seventeenth century, spoke of Yamhad as having a “great kingship,” a term they used only in referring to the most powerful states. We do not know the full extent of Yamhad’s domain, but the Alalakh tablets indicate that city to have been Yamhad’s vassal, as Ugarit on the coast may also have been. To the south Yamhad controlled Ebla, and to the southeast it dominated Emar on the Euphrates. Yamhad maintained its leadership in northern Syria until the opening years of the sixteenth century. Then, during a burst of military energy, the Hittites of what is today central Turkey, led by King Mursilis I, attacked and destroyed Aleppo. Although the Hittites could not exploit their great victory, Yamhad never recovered from the disaster.

To the south of Yamhad the next major power was Qatna. Again, the site itself has provided no written sources, but the city is mentioned in the Mari tablets. It formed the western end of an important trade route that crossed the Syrian desert from Mari, running through Tadmor (Palmyra) to Qatna. This was a much shorter route from Mesopotamia to the southwestern Levant, cutting many miles off the road that looped north along the Euphrates, and it made Qatna one of the major trade hubs of the Near East. The kings of Qatna found it important to befriend whoever controlled Mari, the eastern terminus of the route. When Shamshi-Adad took control of Mari, Ishkhi-Adad of Qatna made an alliance with him, sealing it by marrying his daughter to Shamshi-Adad’s younger son, Yasmah-Adad, now the king of Mari. Such an alliance also greatly benefited Shamshi-Adad, whose northern access to the Mediterranean

Sea Yamhad blocked. But when Zimri-Lim returned to Mari, the new king of Qatna, Amut-pi-el, became his ally, and they too maintained cordial relations. The Mari letters also indicate that Amut-pi-el made peace during this period with Yamhad. Otherwise little is currently known of Qatna.

Even more obscurity shrouds the area south of Qatna. The Mari letters called it the land of Amurru (“the West”), which appears to have consisted of several small kingdoms. We know that the Damascus area was known as the land of Apum, the name also given to the land around Shubat-Enlil in northern Syria. This southerly Apum is mentioned in an Egyptian document, and also apparently in as-yet-unpublished Mari letters. It is here that Egyptian influence begins to outweigh that of Mesopotamia and northern Syria.

The land of Canaan stretched to the south of present-day Damascus. In the second millennium

BCE

, its culture bore some resemblance to that in Syria, but at the same time it had distinctive features. The Canaanite cultural sphere covered all of Palestine, as well as modern Lebanon and coastal Syria as far north as Ugarit. Only peripherally did Palestine enter into the affairs of northern Syria; the predominant outside influence was Egyptian. Complex relationships united the land of Canaan and Egypt during this period, with cultural influences flowing in both directions. Unfortunately, little documentation survives that might lift the veil on Canaan and its affairs. The paltry written sources include a few texts from Egypt and even fewer from Canaan itself. During the first part of the Middle Bronze Age (2000–1700

BCE

, a period contemporary with the Middle Kingdom of Egypt), inscriptions point to a significant Egyptian role in the economic, and perhaps also the political, situation of Canaan. Beginning in the early eighteenth century, Semitic migrants from Canaan began drifting into the delta region of Egypt, and eventually they came to dominate it.