The Oxford History of the Biblical World (27 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

The Israelite

’am

resembles the Islamic

’umma

in that religious allegiance to a single deity, whether Yahweh or Allah, required commitment to the larger “family,” or supertribe. In the case of the early Israelites, they understood themselves to be the “children” of an eponymous ancestor Jacob (who retrospectively became “Israel”) and, at the same time, to be the “people” or “kindred” of Yahweh. It was a religious federation with allegiance to a single, sovereign patriarch or paterfamilias—Yahweh. He was the ultimate patrimonial authority, in Max Weber’s formulation, for those bound to him through covenant as kindred or kindred-in-law.

The Israelite terminology of self-understanding was probably no different from that used by neighboring tribesmen and kinsmen, living east of the Jordan River, who became the kingdoms of Ammon and Moab. The J strand of the Israelite epic preserves an odd tale (Gen. 19.30-38) that could go back to the formative stages of these polities in Transjordan, when various tribal groups were trying to sort out their respective relations and alliances. According to this social etiology, Lot, while drunk, impregnated his two daughters, who then gave birth to Moab (the firstborn) and Ammon, thus making these two “brothers” fraternal “cousins” of Jacob. In the Bible the Ammonites are generally called the “sons of Ammon” (for example, Gen. 19.38; 2 Sam. 10.1) and in the Assyrian annals the “House of Ammon.” In the epic sources (J and E, Num. 21.29; also Jer. 48.46) the Moabites are referred to as the “kindred” of Chemosh, after their sovereign deity.

Through these familial metaphors one sees a series of nested households, which determined position in society and in the hierarchy of being. At ground level was the ancestral house(hold)

(bêt ’āb).

This could be small, if newly established, or extensive, if it had existed for several generations. From the Decalogue it is known that the neighbor’s household included more than the biological members of the family: an Israelite was not to covet his neighbor’s wife, male or female slave, ox or donkey, or anything else that came under the authority of the master of the household (Exod. 20.17; Deut. 5.21). At the state level in ancient Israel and in neighboring polities, the king presided over his house

(bayit),

the families and households of the whole kingdom. Thus, after the division of the monarchy the southern kingdom of Judah is referred to as “house of David”

(byt dwd)

in the recently excavated stela from Dan, and probably also in the Mesha Stela, just as the northern kingdom of Israel is known as the “house of Omri”

(bīt Humri)

in Assyrian texts.

The Philistines were one contingent of a larger confederation known collectively as the Sea Peoples. Beginning about 1185

BCE

and continuing a generation or two, they left their homeland and resettled on the southeast coast of the Mediterranean, in a region that had been occupied by Canaanites for a millennium or more. This movement is documented by a variety of written sources in Akkadian, Ugaritic, Egyptian, and Hebrew, by Egyptian wall reliefs, and by archaeology.

According to the biblical prophets Amos (9.7) and Jeremiah (47.4), the Philistines came from Caphtor, the Hebrew name for Crete; as we shall see, archaeological evidence suggests that this later tradition may preserve an accurate historical memory. Biblical and Assyrian sources indicate that Philistine culture emanated from a core of five major cities—the Philistine pentapolis—located in the coastal plain of southern Canaan (Josh. 13.2-3). For nearly six centuries, during most of the Iron Age, these five cities—Ashdod, Ashkelon, Ekron (Tel Miqne), Gaza, and Gath—formed the heartland of Philistia, the biblical “land of the Philistines.” Each city and its territory were ruled by a “lord” called

seren

in Hebrew (Josh. 13.3), perhaps a cognate of the Greek word

tyrannos

(compare English “tyrant”). Four of the five cities have been convincingly located. Ashdod, Ashkelon, and Ekron have been extensively excavated; Gaza, which lies under the modern city of the same name, has not. Gath is usually located at Tell es-Safi, but its proximity to Ekron makes this unlikely.

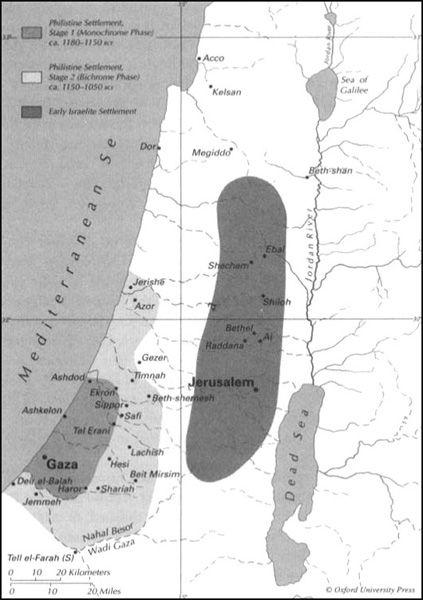

The Expansion of Philistine Settlement, ca. 1180-1050

BCE

The archaeology of the Philistines can be divided into three stages:

Stage 1

(ca. 1180-1150

BCE

). The Philistines arrive en masse on the coast of southwest Canaan. The path of destruction along coastal Cilicia, Cyprus, and the Levant suggests that these newcomers came by ship in a massive migration that continues throughout most of Stage 1, and perhaps into Stage 2. They destroy many of the Late Bronze Age cities and supplant them with their own at the four corners of their newly conquered territory, which extends over some 1,000 square kilometers (386 square miles). During Stage 1 the Philistines control a vital stretch of the coastal route, or “Way of the Sea,” which had usually been dominated by the Egyptians and their Canaanite dependencies.

During this stage the Philistines have much the same material culture as other Sea Peoples. The process of acculturation has not yet begun, which will lead to regional differences among the various groups of Sea Peoples. In their new settlements along the eastern Mediterranean coast and along the coast of Cyprus, the new immigrants share a common pottery tradition, brought or borrowed from Aegean Late Bronze Age culture. It is a style of Mycenaean pottery, locally made, which is usually classified as Mycenaean IIIC:lb (hereafter Myc IIIC).

Along with this shared potting tradition, the Philistines bring other new cultural traditions to Canaan: domestic and public architecture focusing on the hearth; weaving with unperforated loom weights; swine herding and culinary preference for pork; drinking preference for wine mixed with water; and religious rituals featuring female figurines of the mother-goddess type. Most of these cultural elements are found in the earlier Mycenaean civilization, which flourished during the Late Bronze Age on the Greek mainland, in the islands, especially Crete (Caphtor), and at some coastal enclaves of Anatolia. Around the Philistine heartland, Egypto-Canaanite cultural patterns persist well into the twelfth century as Egyptians garrisoned in predominately Canaanite population centers try to contain the Philistines.

Stage

2 (ca. 1150-1050

BCE

). With the breakdown of Egyptian hegemony in Canaan after the death of Rameses III (1153

BCE

), the Philistines begin to expand in all directions beyond their original territory, north to the Tel Aviv area, east into the foothills (Shephelah), and southeast into the Wadi Gaza and Beer-sheba basin. Their characteristic pottery is known as Philistine bichrome ware, which, like other items, shows signs of contact and acculturation with Canaanite traditions.

Early in this stage, the Israelite tribe of Dan seems to have been forced to migrate from the coastal plain and interior to the far north, though remnants of that tribal group remained in the foothills. The Samson saga (Judg. 13-16) illustrates limited Philistine and Israelite interaction along the boundaries shared by two distinctive cultures, Semitic and early Greek.

Stage 3

(ca. 1050-950

BCE

). Through acculturation, Philistine painted pottery loses more and more of its distinctive Aegean characteristics. The forms become debased, but they are still recognizable. The once-complex geometrical compositions and graceful motifs of water birds and fishes of stage 2 bichrome ware are reduced to simple spiral decorations (if any at all) painted over red slip, which is frequently burnished.

This process of acculturation in the material repertoire does not, however, signal assimilation or loss of ethnic identity among the Philistines. As a polity they are never

stronger. During the latter half of the eleventh century

BCE

their expansion into the highlands triggers numerous conflicts and outright war with the tribes of Israel. Philistine military advances into the Israelite highlands are so successful, and the crisis among the Israelites so great, that the latter demand the new institution of kingship.

After the investiture of the successful warlord David as king over a fragile yet united kingdom, the tide of battle eventually turned against the Philistines. By 975

BCE

David and his armies have pushed the Philistines back into the coastal territory controlled by the pentapolis, finally completing the Israelite “conquest” of Canaan.

The most ubiquitous and most distinctive element of Philistine culture, and a key in delineating the stages summarized above, is their pottery. The Myc IIIB pottery of the Late Bronze Age was imported into the Levant, whereas all the Myc IIIC wares found in the pentapolis in the early Iron Age were made locally. When Myc IIIC (stage 1) pottery from Ashdod and Ekron in Philistia or from Kition, Enkomi, and Palaeopaphos in Cyprus is tested by neutron activation, the results are the same: it was made from the local clays. This locally manufactured pottery was not the product of a few Mycenaean potters or their workshops, brought from abroad to meet indigenous demands for Mycenaean domestic and decorated wares, as the large quantities found at coastal sites from Tarsus to Ashkelon demonstrate. At Ras Ibn Hani in Syria and at Ekron, locally made Mycenaean pottery constitutes at least half of the repertoire, at Ashdod about 30 percent. Local Canaanite pottery, principally in the forms of store jars, juglets, bowls, lamps, and cooking pots, makes up the rest of the assemblage in the pentapolis.

The appearance in quantity of Myc IIIC in Cyprus and the Levant heralds the arrival of the Sea Peoples. At Ashdod, Ashkelon, and Ekron new settlements characterized by Myc IIIC pottery were built on the charred ruins of the previous Late Bronze Age II Canaanite, or Egypto-Canaanite, cities. These Philistine cities were much larger than those they replaced. This new urban concept and its impact on the landscape will be discussed further below.

Stage 2 Philistine pottery is a distinctive bichrome ware, painted with red and black decoration, a regional style that developed after the Philistines had lived for a generation or two in Canaan. To the basic Mycenaean forms in their repertoire they added others from Canaan and Cyprus, and they adapted decorative motifs from Egypt and a centuries-old bichrome technique from Canaan.

This bichrome ware was once thought the hallmark of the first Philistines to reach the Levant, early in the reign of Rameses III. An earlier contingent of Sea Peoples had fought with the Libyans against the Egyptian pharaoh Merneptah, but the Philistines were not among them. This pre-Philistine or first wave of Sea Peoples supposedly brought the Myc IIIC potting traditions to the shores of Canaan, where they founded the first cities on exactly the same sites later identified with the Philistine pentapolis.

But the battle reliefs of Merneptah make it clear that Ashkelon, the seaport of the pentapolis, was inhabited by Canaanites, not Sea Peoples, during that pharaoh’s reign. The simplest explanation is that the confederation of Sea Peoples, including the Philistines,

mentioned in texts and depicted in reliefs of Rameses III were the bearers of Myc IIIC pottery traditions, which they continued to make when they settled in Canaan. The stylistic development from simple monochrome to more elaborate bichrome was an indigenous change two or three generations after the Philistines’ arrival in southern Canaan. The eclectic style of bichrome pottery resulted not from a period of peregrinations around the Mediterranean during the decades between Merneptah and Rameses III, but from a process of Philistine acculturation, involving the adaptation and absorption of many traditions to be found among the various peoples living in Canaan. This acculturation process continued among the Philistines throughout their nearly six-hundred-year history in Palestine.

As one moves from core to periphery in the decades following stage 1, the material culture of the Philistines shows evidence of spatial and temporal distancing from the original templates and concepts. Failure to understand the acculturation process has led to the inclusion of questionable items in the Philistine corpus of material culture remains, such as the anthropoid coffins (or worse, to a denial of a distinct core of Philistine cultural remains) just two or three generations after their arrival in Canaan at the beginning of stage 2 (ca. 1150

BCE

).

Shortly before the final destruction of Ugarit, a Syrian named Bay or Baya, “chief of the bodyguard of pharaoh of Egypt,” sent a letter in Akkadian to Ammurapi, the last king of Ugarit. Bay served under both Siptah (1194-1188) and Tewosret (1188-1186). His letter arrived at Ugarit while Myc IIIB pottery was still in use. At nearby Ibn Hani, however, the Sea Peoples built over the charred ruins of the king’s seaside palace, which contained Myc IIIB ware. More than half of the ceramic yield from their new settlement was Myc IIIC pottery, a proportion comparable to that of stage 1 settlements in Philistia. The final destruction of Ugarit, as well as of many other coastal cities in the eastern Mediterranean, occurred only a decade or so before the events recorded by Rameses III (1184-1153) in his eighth year: