The Oxford History of the Biblical World (24 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

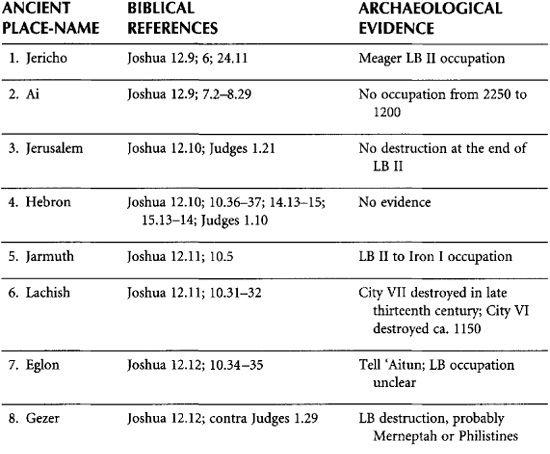

Table 3.1 Cities in Joshua 12.9-24

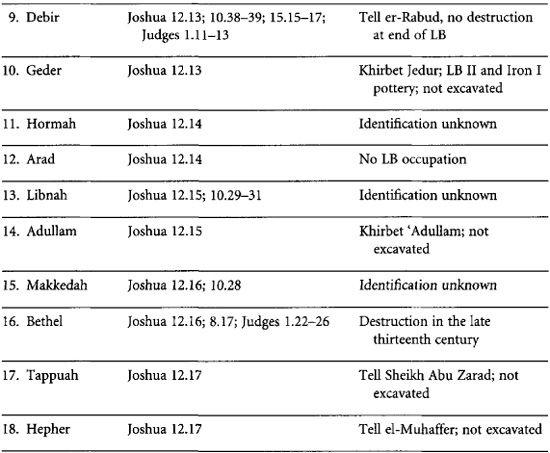

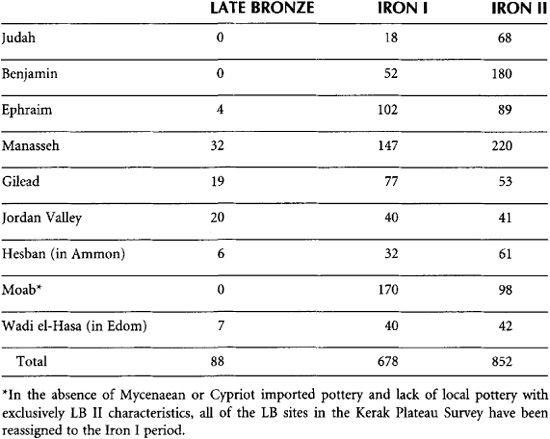

Table 3.2 Survey of Sites by Region and Period Appearing on Settlement Maps

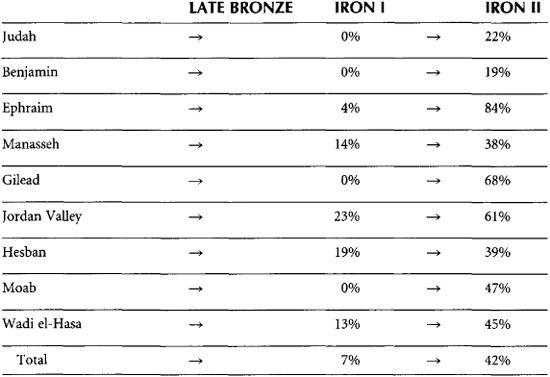

Recent attempts to distinguish movements from east of the Jordan into the west, or vice versa, lack sufficiently precise chronological control to be convincing. What can be said is that Iron Age I settlements throughout the highlands display a similar material culture, which is best identified with rural communities based on mixed economies of agriculture and sheep-goat herding. That many of these villages belonged to premonarchic Israel (as known from Judg. 5 and perhaps from the Merneptah Stela) is beyond doubt. This is especially clear from the continuity of settlement patterns from Iron Age I into Iron Age II (see

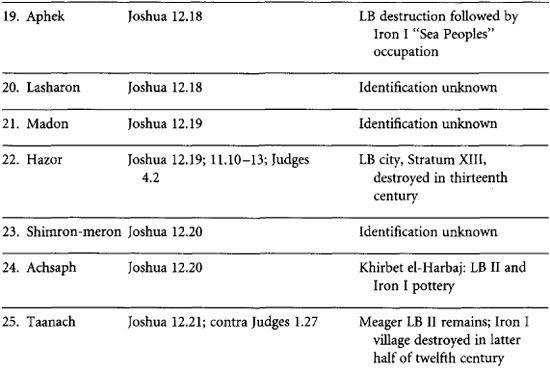

table 3.3

) in the survey zones of Ephraim, Manasseh, and Gilead, the heartland of monarchic Israel.

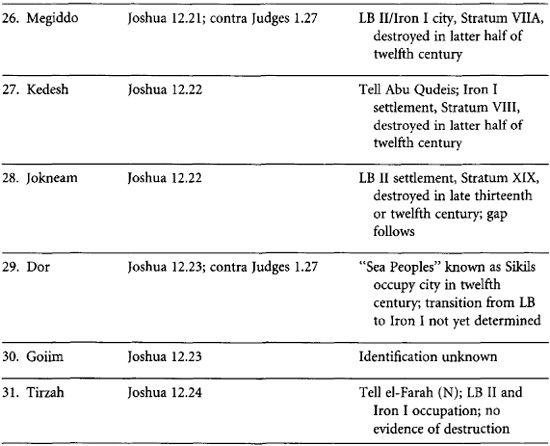

Table 3.3 Continuity of Settlement Patterns from Late Bronze Age II to Iron Age I and from Iron Age I to Iron Age II

Biblical sources indicate that premonarchic Israel was structured according to tribal principles of social organization. Archaeology is providing support for understanding the social organization of premonarchic Israel and other Transjordanian polities (for example, Moab, Midian, Ammon) as kin-based, “tribal” societies. In the Iron Age I highland villages, the heartland of early Israel, it is possible to distinguish multiple family compounds, such as those at Khirbet Raddana. These family compounds, comprised of two or three houses set off from their village surroundings by an enclosure wall, formed the basic socioeconomic units of the community, usually with a population of no more than one hundred to two hundred persons per village. In such villages, the extended or multiple family unit was the ideal type. Such a household may have constituted a minimal “house of the father” (Hebrew

bêt ’āb),

or a small patrilineage.

Further clues to the composition of early Israelite villages can be deciphered from compound place-names. The first element of the place-name reveals the settlement type, such as “hill,” “enclosure,” “diadem”; the second element, the name of the founding families or leading lineages. Examples are Gibeah (“hill”) of Saul (1 Sam. 11.4), Hazar (“enclosure of”)-addar (Num. 34.4), Ataroth (“diadem of”)-addar (Josh. 16.5), and Ataroth-beth-joab (“diadem of the house of Joab”; 1 Chron. 2.54). Likewise, on the regional level territories could take their names from the dominant large families, either lineages or clans, who lived there. Samuel, a Zuphite, lived at

his ancestral home at Ramah, or Ramath(aim)-zophim, named after his Ephraimite ancestor (1 Sam. 1.1), in the land of Zuph, through which Saul passed in search of his father’s lost asses (1 Sam. 9.5). District or clan territories remained important subdivisions of tribal society even during the monarchical period, as the Samaria ostraca attest.

Without clear indications from texts, it is doubtful that archaeologists can distinguish one highland group from another. The cluster of material culture, which includes collared-rim store jars, pillared houses, storage pits, faunal assemblages of sheep, goat, and cattle (but little or no pig), may well indicate an Israelite settlement, but this assemblage is not exclusively theirs. Giloh and Tell el-Ful (Saul’s Gibeah) are generally considered to be “Israelite” villages, but they have many things in common (for example, collared-rim store jars) with neighboring “Jebusite” Jerusalem and “Hivite” Gibeon. “Taanach by the waters of Megiddo” seems to be Canaanite in the Song of Deborah, yet its material culture is hardly distinguishable from that of the highland villages. There is a greater contrast between the twelfth-century city of Canaanite Megiddo (Stratum VILA) and the contemporary Canaanite village of Taanach than between putative Israelite and Canaanite rural settlements. The differences derive more from socioeconomic than from ethnic factors.

The evidence from language, costume, coiffure, and material remains suggest that the early Israelites were a rural subset of Canaanite culture and largely indistinguishable from Transjordanian rural cultures as well.

In 1925 the German scholar Albrecht Alt articulated the second regnant hypothesis to explain the appearance of early Israel. Alt used texts to compare the “territorial divisions” of Canaan with those of the Iron Age. From this brilliant analysis, made without the aid of archaeology, Alt concluded that early Israel evolved from pastoral nomadism to agricultural sedentarism.

This interpretation, which has held sway especially among German scholars, accepts the biblical notion that the Israelites were outsiders migrating into Canaan from the eastern desert steppes as pastoral nomads, specialists in sheep and goat husbandry. These clan and tribal groups established more or less peaceful relations with the indigenous Canaanites, moving into more sparsely populated zones, such as the wooded highlands of Palestine or the marginal steppes—areas outside the domain of most Canaanite kingdoms and beyond the effective control of their overlords, the Egyptians. These pastoralists have sometimes been identified specifically with a wide-ranging group called the Shasu in Egyptian texts dating from 1500 to 1150

BCE

. They appear as mercenaries in the Egyptian army, but more often they are regarded as tent-dwelling nomads who raise flocks of sheep and goats. Their primary range seems to be in southern Edom or northern Arabia (known as “Midian” in the Bible). In Merneptah’s time, Egyptians recognized the “Shasu of Edom.” A Dynasty 18 list mentions among their tribal territories the “Shasu-land of Yahweh,” perhaps an early reference to the deity first revealed to Moses at Horeb/Sinai in the land of Midian (see below).

Recent anthropological research has rendered obsolete the concept of the pastoral nomads who subsist on the meat and dairy products they produce and live in blissful

solitude from the rest of the world. Equally outworn is the concept of seminomadism (still embraced by too many scholars of the ancient Near East) as a rigid ontological status, marking some cultural (pseudo-)evolutionary stage on the path to civilization, from desert tribesman to village farmer to urban dweller: in archaeological parlance, the “from tent-to-hut-to-house” evolution.

Scholars of the ancient Near East are only recently rediscovering what the great fourteenth-century

CE

Arab historian Ibn Khaldun knew well. In his classic

Muqaddimah: An Introduction to History,

he observed:

Desert civilization is inferior to urban civilization, because not all the necessities of civilization are to be found among the people of the desert. They do have some agriculture at home but do not possess the materials that belong to it, most of which [depend on] crafts. They have… milk, wool, [camel’s] hair, and hides, which the urban population needs and pays Bedouins money for. However, while [the Bedouins] need the cities for their necessities of life, the urban population needs [the Bedouins] for conveniences and luxuries, (p. 122; trans. Franz Rosenthal, abr. and ed. by N. J. Dawood, Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1967)

The Israeli archaeologist Israel Finkelstein has adapted and updated Alt’s nomadic hypothesis to explain the hundreds of new settlements that have been recorded in archaeological surveys. But it is difficult to believe that all of these new-founded, early Iron Age I settlements emanated from a single source, namely sheep-goat pastoralism. In symbiotic relations the pastoral component rarely exceeds 10 to 15 percent of the total population. Given the decline of sedentarists in Canaan throughout the Late Bronze Age, it seems unlikely that most of the Iron Age settlers came from indigenous pastoralist backgrounds.

The third leading hypothesis to account for the emergence of ancient Israel was posed by George E. Mendenhall and elaborated further by Norman Gottwald. For them, the Israelites consisted mainly of oppressed Canaanite peasants who revolted against their masters and withdrew from the urban enclaves of the lowlands and valleys to seek their freedom elsewhere, beyond the effective control of the urban elite. In this sense, they represent a parasocial element known as the Apiru in second-millennium

BCE

texts from many parts of the Near East. Moshe Greenberg has characterized them as “uprooted, propertyless persons who found a means of subsistence for themselves and their families by entering a state of dependence in various forms. A contributory factor in their helplessness appears to have been their lack of rights as foreigners in the places where they lived. In large numbers they were organized into state-supported bodies to serve the military needs of their localities. Others exchanged their services for maintenance with individual masters”

(The Hab/piru,

New Haven, Conn.: American Oriental Society, 1955, p. 88). These were propertyless persons in a state of dependency on a superior. They might be servants in a household or hired laborers. In hard economic times and periods of social disintegration, they became gangs of freebooters and bandits under the leadership of a warlord, such as Jephthah (Judg. 11) or David before he became king. Whether this was a revolution from the bottom up, which resulted in the new Yahwistic faith (according to Gottwald), or

whether the new faith served as the catalyst for revolutionary change (according to Mendenhall), both variants of the “peasants’ revolt” hypothesis consider the participants to be insiders, not outsiders—an underclass of former Canaanites who took on a new identity as they joined the newly constituted community “Israel.”