The Oxford History of the Biblical World (53 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Were prophets agents of revolution? Ahijah commissioned both Jeroboam and Baasha to rebel against existing authority. Omri received no such prophetic warrant, but Jehu did. Yet the prophet is not pictured as a revolutionary. At most, the prophet speaks for a combination of divine displeasure and human disillusionment. No complete contrast separates the prophets’ commissionings of Jeroboam, Baasha, and Jehu from the commissioning of Omri by a popular movement of the army. At the Shechem assembly, Jeroboam’s divine commissioning by Ahijah is wedded to the human circumstance of outcry against unjust rule. Both sets of circumstances reveal

the central issue of good governance and the pursuit of justice for people, a check upon royal prerogative. And good governance fundamentally means the practice of loyalty to God.

The prophetic story in 1 Kings 21 stands out. Ahab has a palace in a town called Jezreel (see 1 Kings 18.45–46), lying at the edge of the valley of the same name some 50 kilometers (30 miles) north of Samaria. (The spot is prominent enough in the biblical record to have suggested to some scholars that it was the second capital of the country during the Omri dynasty, perhaps the one where Ahab expressed his loyalty to Israel’s deity through a shrine, while Samaria served as the seat of Baal worship.) At Jezreel, Ahab had a family holding.

Naboth also held property in Jezreel, a vineyard that Ahab wanted in exchange. The scenario is based on a patrimonial land tenure system. Naboth’s response to Ahab expresses it: this land is inalienable, ancestral. Naboth holds the upper hand, and the king knows it; kings in Israel are bound by the same system as everyone else. Queen Jezebel, however, has a different perspective: “Are you the king of Israel or not?” Using the royal seal, Jezebel then contrives Naboth’s downfall and death, and the king takes the land he wanted. Perhaps Ahab and Naboth were related, and Ahab became heir as next in line; or perhaps an otherwise unknown practice allowed the crown to confiscate land owned by a convicted criminal.

Ahab goes to take possession, and Elijah is there to greet him. The end of the dynasty is announced, on the pattern that had ended Jeroboam’s and Baasha’s dynasties, but because Ahab humbles himself, the divine decision is deferred until Ahab’s son’s days. But Jezebel, and Ahab through her, will be used by the DH as the symbolic violator of norms.

Other episodes in the cycle of stories about Elijah and Elisha provide information that we cannot take as a record of political history, but which does presume social custom and thus yields insight into social history. An instance comes from 2 Kings 8.1–6. Elisha has lodged with a family in Shunem in the Jezreel Valley; in a story in 2 Kings 4.8–37, he has brought the family’s dead son back to life. In that story, the woman of the household, pictured as wealthy, is clearly the active agent, and her husband an aging foil. In 8.1–6, the same woman has been told by Elisha to resettle in Philistia because of an impending seven-year famine in Israel. Upon her return, she appeals to the king for the return of her house and land, and he sends an official to see that she gets her holdings back, together with the revenue her fields yielded to whoever took them over in her absence. The glimpse here of a system of redress, and the fact that women held property and maintained usufruct, are factors in Israelite social practice that do not appear clearly if one takes as guides the collections of law preserved in Exodus, Leviticus, and Deuteronomy. In the common life of Israel, custom and system delivered justice, in this case apparently for a now-widowed person. And the prophetic role includes seeing that such justice is done.

Obscure events of the year 843/842

BCE

brought the Omri-Ahab dynasty to an end. According to the Assyrian evidence, Hadadezer has been the king in Damascus; Shalmaneser’s inscriptions record him as an opponent in battles on the Orontes between 853 and 845. Another Shalmaneser text reports that he defeated Hadadezer and that Hadadezer died; Hazael, a usurper, took the throne. The text seems to connect the death and the usurpation but says nothing about a murder.

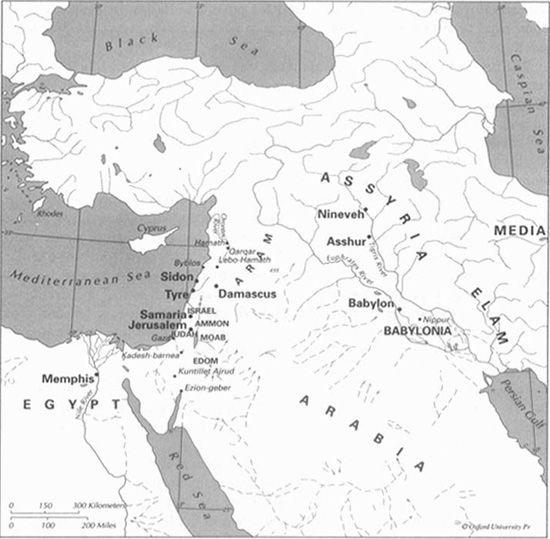

The Near East during the Assyrian Empire

The DH’s selection of materials about relations with Syria during Ahab’s reign (1 Kings 20; 22; 2 Kings 6.24–7.20) speaks instead of a Ben-hadad, king of Aram (chapter 22 gives the Syrian king only his title, no name). The series culminates in 2 Kings 8.7–15, which reports a visit of Elisha to Damascus during an illness of Ben-hadad. Hazael, in attendance upon Ben-hadad, goes to meet Elisha, and Elisha tells Hazael he will be king of Aram. Hazael thereupon smothers his master and becomes his successor.

As we have already noted, there is legitimate reason to doubt the names of the participants in the stories of Israelite-Syrian battles in 1 Kings 20 and 22 and to suspect that the events belong to a later period. The episode in 2 Kings 6–7 has similar problems: Ben-hadad appears in 6.24, but otherwise no royal figure in the chapter is named. The assertion that Hazael killed Ben-hadad in 2 Kings 8.15 is plain, however, so the discrepancy in the Assyrian and biblical evidence remains.

Proposals to resolve the discrepancy abound. One is to assume that Hadadezer

and Ben-hadad are names for the same person, the latter perhaps a typical Syrian throne name. Both sources would then be accurate. A more elaborate theory is that since Shalmaneser’s words are ambiguous about a murder and supplanting by Hazael, there was a son of Hadadezer named Ben-hadad, “Ben-hadad II,” who reigned for two or three years after Hadadezer’s death and before Hazael’s usurpation. A third proposal is to claim that Ben-hadad’s name is a late addition to the 2 Kings 8 depiction of the death of the king of Aram, which originally had Hadadezer or gave no king’s name; thus the biblical account would now be in error. The upshot is that there is a Ben-hadad of Damascus who reigns throughout the early ninth century, then Hadadezer whom Shalmaneser encountered at Qarqar, contemporary with much of Ahab’s reign, possibly a Ben-hadad II for a couple of years, and finally Hazael.

The DH gives the overall impression of protracted strife between Israel and the Syrian state of Damascus, with periods of cooperation interspersed (note the three-year respite in 1 Kings 22.1). The alliance for the battle at Qarqar would be one such interlude. The short story of Naaman, the Syrian army commander with leprosy whom Elisha treats with the medicine of the waters of the Jordan (2 Kings 5), suggests both conflict—an Israelite slave girl in Naaman’s house—and benign interaction. And whatever decision scholars may reach about the historical settings of the battles in 1 Kings 20 and 22, the account in 20.31–34 speaks of the relationship between the Israelite king and the Syrian king as one of “brotherhood”—that is, treaty-connection—and the placement of bazaars in Damascus and Samaria means reciprocal commercial activity. Less certain is the frequent proposal that ninth-century destruction levels at Dan or Hazor or Shechem result from Syrian military incursions.

The stela from Dan is a case in point. Hazael has clashed with Jehoram of Israel and Ahaziah of Judah in 843

BCE

, according to 2 Kings 8.28–29. These two met their deaths either at the hands of Jehu (9.14–28) or at the hands of Hazael himself (the stela, if correctly read). Both the stela and the DH, with the Chronicler in substantial agreement (2 Chron. 22), picture the period leading up to 842 as a time of cooperation between Judah and Israel.

Few sources outside the Bible say much about Judah in the ninth century

BCE

. No Judean king figures in the Assyrian records, and the Dan stela is the only nonbiblical evidence about relations between Judah and Israel. This led a few historians to wonder whether a Davidic royal establishment and a “covenant with David” might be a fiction, retrojected into the past from Josiah’s time or even from the time of the Babylonian exile—that is, from the late seventh or sixth centuries

BCE

. But this hypothesis has been destroyed by the discovery of the Dan stela, with its inescapable reference to the “house of David.”

At Arad, guarding the Judean southern frontier, 25 kilometers (15 miles) west of the Dead Sea, the date of the Solomonic fortress (Stratum XI) has been disputed and may belong to the early ninth century

BCE

. Beer-sheba, west of Arad in the central northern Negeb, was a fortified Judean town substantially to the south of Rehoboam’s string of frontier fortifications, suggesting that Asa’s or Jehoshaphat’s control extended farther to the south than had Rehoboam’s.

Asa’s long reign (roughly 908–867

BCE

) extended into the opening years of the Omri dynasty, but it was his son Jehoshaphat who ruled Judah throughout Ahab’s

reign. The DH ushers Jehoshaphat onto the scene in 1 Kings 15.24, in Asa’s death notice; it includes him in the Micaiah story and the battle to recover Ramoth-gilead of 1 Kings 22.1–28; and then it gives a brief summation of his reign in 1 Kings 22.41–50. As with Asa, the Chronicler presents significantly more about Jehoshaphat, while giving alternative angles on two of the features the DH had included. The Chronicler criticizes Jehoshaphat for his participation with Israel’s king in the Ramoth-gilead battle (2 Chron. 19.1–3), and his narrative about a maritime venture of Jehoshaphat and Ahaziah, son of Ahab, differs strikingly from the DH’s account.

This maritime venture involved an effort to build and deploy a mercantile fleet at Ezion-geber, the port at the northern tip of the Red Sea. In 1 Kings 22.47–49, the information is as follows:

There was no king in Edom; a deputy was king. Jehoshaphat made ships of the Tarshish type to go to Ophir for gold; but they did not go, for the ships were wrecked at Ezion-geber. Then Ahaziah son of Ahab said to Jehoshaphat, “Let my servants go with your servants in the ships,” but Jehoshaphat was not willing.

The Chronicler has it this way:

After this King Jehoshaphat of Judah joined with King Ahaziah of Israel who did wickedly. He joined him in building ships to go to Tarshish; they built the ships in Ezion-geber. Then Eliezer son of Dodavahu of Mareshah prophesied against Jehoshaphat, saying, “Because you have joined with Ahaziah, the L

ORD

will destroy what you have made.” And the ships were wrecked and were not able to go to Tarshish. (2 Chron. 20.35–37)

Manifestly the Chronicler opposed Judean alliances with kings of Israel; the story is retold to make the maritime venture a disapproved cooperative one, and it implies that Israel took the initiative, perhaps already having access to Ezion-geber.

The brief notices about this venture suggest that if Judah and Israel could cooperate, working out (by either treaty or submission) arrangements with Phoenicia to the north and Edom to the south, then they could develop on the land bridge from the Mediterranean to the Red Sea a lucrative and mutually beneficial commercial program. The note from 1 Kings 22.47 affirms Edom’s compliance, forced or otherwise. The northern end of the trade route was secure with Ahab’s relationship to Sidon and Tyre.

Probably the commercial program worked. Current understanding of the archaeological sequence at Tell el-Kheleifeh confirms its identification as the site of Eziongeber. It still supports Nelson Glueck’s original assignment of a stratum to the first half of the ninth century

BCE

—Jehoshaphat’s time. But the only notice about its role as a factor in the economic life of Judah at this time has to do with the wreck of the fleet, apparently before it ever set sail. And for the Chronicler the story provides an object lesson in Jehoshaphat’s wickedness.

Ingredients such as these two “reversals” of DH materials have led historians to question whether the Chronicler can be trusted for historical information. But a strong theme in the Chronicler’s account commends itself as historical: the twin efforts at administering justice and instructing in just practice. Jehoshaphat’s name,

probably a throne name, means “Yahweh has judged,” or better, “Yahweh has seen to justice.” In 2 Chronicles 17.7–9 and 19.4–11, Jehoshaphat is reported to have dispatched officials and Levitical educators throughout Judah. They had “the book of the law of the L

ORD

with them,” which sounds like an anachronism consistent with the time of Ezra and Nehemiah, but their task was to inculcate justice in the land and to deal with cases in Judah’s fortified cities. Reference is also made to a Judean “court of appeals” in Jerusalem. Consistent administration of law under the royal aegis is plausible enough and may even have been an improvement on local administration. What such efforts to ensure justice would have run up against is perhaps best seen from Ruth 4. Here, a complex set of issues involving land ownership, land transfer, inheritance, and marriage are interwoven in a case requiring the elders of the town and two disputants to work out a satisfactory resolution. Another instance, with a far less benign outcome, forms part of the drama in the Naboth vineyard story, where a trumped-up charge brings down a local notable. There is good reason to credit the tradition of judicial reform under Jehoshaphat, and to connect it with the introduction (or reinstitution) of a district system in Judah suggested by Joshua 15.21–62 and in Benjamin in Joshua 18.21–28. Solomon had districted the north, but there has been no report of a similar administrative move in the south. Jehoshaphat’s construction of store-cities and fortresses (2 Chron. 17.12) would have been part of such an administrative reform.