The Oxford History of the Biblical World (49 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Holladay, John S., Jr. “The Kingdoms of Israel and Judah: Political and Economic Centralization in the Iron IIA-B (ca. 1000–750

BCE

).” In

The Archaeology of Society in the Holy Land,

ed. Thomas E. Levy, 368–98. New York: Facts on File, 1995. A masterful look at social, political, and economic aspects of the monarchy, using archaeological data and social-science models in groundbreaking ways.

Ishida, Tomoo, ed.

Studies in the Period of David and Solomon and Other Essays.

Tokyo: Yamakawa-Shuppansha, 1982. A useful collection of essays by leading biblical scholars and archaeologists on various features of the United Monarchy.

Knight, Douglas A. “Political Rights and Power in Monarchic Israel.” In

Ethics and Politics in the Hebrew Bible, Semeia 66,

ed. Douglas A. Knight and Carol Meyers, 93–118. Atlanta: Scholars Press, 1995. A thoughtful look at political rights and privileges at both local and national levels during the monarchy.

Malamat, Abraham, ed.

The Age of the Monarchies.

World History of the Jewish People, no. 4. Jerusalem: Massada, 1979. A somewhat dated but handy anthology of articles by leading scholars about the monarchy, in two volumes: 1, Political History; 2, Culture and Society.

Mazar, Amihai. “The United Monarchy” and “General Aspects of Israelite Material Culture.” In

Archaeology of the Land of the Bible 10,000–586

B.C.E

.,

chaps. 9 and 11. New York: Doubleday, 1990. A balanced presentation of the archaeological evidence for the early monarchy.

Meyers, Carol. “David as Temple Builder.” In

Ancient Israelite Religion: Essays in Honor of Frank Moore Cross,

ed. Patrick D. Miller Jr., Paul D. Hanson, S. Dean McBride, 357–76. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1987. An examination of David’s building activities, including the beginning of temple construction, as part of imperial domination.

——. “The Israelite Empire: In Defense of King Solomon.” In

Backgrounds for the Bible,

ed. David Noel Freedman and Michael Patrick O’Connor, 181–98. Winona Lake, Ind.: Eisenbrauns,

1987. An analysis of Solomon’s policies as necessary for maintaining his father’s regime rather than as exploitative royal materialism.

——. “Temple, Jerusalem.” In

Anchor Bible Dictionary,

ed. David Noel Freedman, 6.350–69. New York: Doubleday, 1992. A full treatment of the architectural and artistic features as well as the symbolic, religious, economic, and sociopolitical aspects of the Temple built by Solomon and its successors.

A Land Divided

Judah and Israel from the Death of Solomon to the Fall of Samaria

EDWARD F. CAMPBELL JR.

S

olomon died in 928

BCE

, amid severe strains in Israel’s body politic and on the international scene. Almost immediately, his state was split into two unequal parts, to be centered on Samaria in the north and Jerusalem in the south. Two hundred years later, Assyria would put an end to the era that had started with Solomon’s death, destroying Samaria’s society and infrastructure and so threatening Jerusalem that its life could never again be the same. This troubled era is the focus of this chapter.

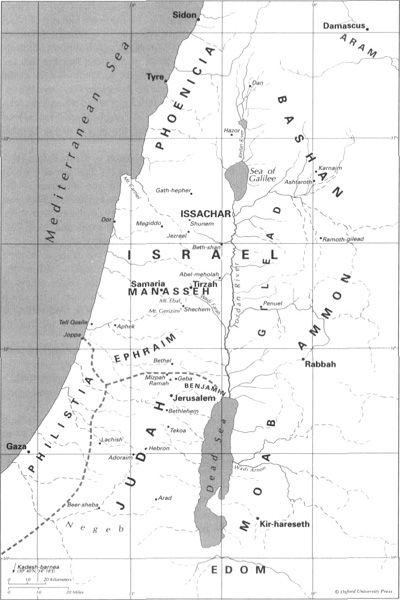

The two political entities, self-designated as “Israel” and “Judah,” rubbed against one another at a boundary in the tribal territory of Benjamin, only 15 kilometers (10 miles) north of Jerusalem. Beginning there, the boundary curved south and east, encompassing within Israel all the fertile Jordan Valley. To the west the line ran to the Mediterranean, meeting the boundary of Philistia as it neared the coast. Israel held the coast from the Mount Carmel peninsula past Dor to Joppa, between Phoenicia and Philistia. At times the Israel-Judah borderline was contested, but mostly it just existed and was probably quite permeable. To judge from the earlier history of the land and from settlement patterns, the boundary followed a line of social and cultural fracture of long duration. In the fourteenth-century Amarna period, two city-states had flanked it, Shechem in the central hill country and Jerusalem. Ancient settlements known from archaeological surveys are more numerous from Bethel to Jerusalem and around Shechem; a strip of land from Ramallah to the Valley of Lubban between these two clusters had few ancient sites. When they were strong, the two kingdoms together controlled the same territory as had the Davidic-Solomonic empire, but in times of weakness they both contracted drastically.

Even when strong, Israel was separated from the Mediterranean by the extended

strip of the Phoenician coast, though generally relations between Israel and the Phoenicians were established by treaty and remained stable. To the north and east of Israel lay the Aramean states of modern Syria, notably the kingdoms centered on Hamath and Damascus. Israel’s conflicts were mostly with Damascus, which almost constantly contested its control of northern Transjordan. Much of the time, Israelite rule extended from the regions of Gilead and Bashan southward to Moab—as far as the Arnon River, which reaches the Dead Sea halfway down its eastern shoreline. Whenever Moab submitted to Israel, Israel’s influence reached farther south and encountered Edom near the south end of the Dead Sea. Ammon, lying between Israelite land and the desert to the east, played a minor role during the period of the Divided Monarchy.

Judah, by contrast, was effectively landlocked. To its south in the forbidding territory of the northern Negeb, reaching down to the tip of the Red Sea at Elath, it vied with Edom. When strong, Judah held the copper and iron resources of the Arabah, and it exported and imported through Elath. Its core territory, though, was a rough rectangle lying between the boundary with Israel in the north and Beer-sheba and Arad to the south—about 80 kilometers (50 miles) north-south and, from Philistia to the Dead Sea, hardly 60 kilometers (38 miles) east-west.

When rulers of the north and south could cooperate and were strong in relation to their neighbors, they controlled the trade routes through the region, both north-south and east-west. Israel had better rainfall and contained the fertile valleys of Jezreel and the Jordan, but Judah held the key to the mineral resources in the south and to the port that gave access to Africa and the Arabian Peninsula. Controlling as they did the land bridge between Eurasia and Africa, both constituted crucial interests for Egypt and Mesopotamia.

The character of the land had an important role in determining the internal well-being of the people and in shaping their relations with neighboring nations. From the boundary south to Jerusalem and past it to the Bethlehem-Hebron region, Judah’s land was hilly and cut by extended valleys. Average rainfall diminishes significantly from north to south, and agricultural potential diminishes with it. South of Bethlehem and Hebron stretches even more arid territory, extending to a line from Gaza on the Mediterranean southeast to Beer-sheba and east to Arad, thence to the Dead Sea at a point opposite the south point of the Lisan peninsula, some three-quarters of the way down the Dead Sea coast. With Beer-sheba begins the Negeb, unsuitable for permanent settlement except around oases (Kadesh-barnea, for example), unless specific measures were taken to provision outposts and fortresses.

In Israel, the territory of Ephraim and Manasseh constituted the central highlands, limestone hills with thin soil cover surrounding upland valleys of quite fertile soil. The hills receive enough rain to sustain grain crops and fruit trees, although rainfall amounts vary from year to year and water was (and is) always a matter of concern. Springs, some of them very abundant, flow from the tilted limestone layering of the hills and provide sufficient water for settlements. This central highland region extends to the Jezreel Valley, which angles from the northeast slopes of Mount Carmel southeast to Beth-shan near the Jordan. The valleys were kept free of settlement and covered with agricultural parcels; the villages and towns lay on the low flanks of the hills, while agricultural terracing extended on the adjacent slopes around and above the villages. Terraces represented in some sense discretionary land—expandable, capable of supporting grain crops, olive and fig trees, and vineyards. Creating terraces, however, was slow work and required patience for the soil to become viable; terraces were no answer to emergencies, such as drought.

The Divided Monarchy: Judah and Israel from 928 to 722

BCE

The ancient historians of Israel reflect, mostly indirectly, a good deal about these enduring conditions. Their focus, however, is on the course of political history. One of them, the author of the Deuteronomic History (designated “DH” by modern scholars), recounted the story in the books of Kings. The DH was probably first compiled in the eighth century

BCE

, given definitive form under Josiah in the late seventh century, and augmented in the exile. The other ancient historian, now known as the “Chronicler,” composed an edition of the books of Chronicles in the late sixth century that was greatly augmented in subsequent periods.

Both histories saw the division of the monarchy in 928 as a critically important event. The DH used the north’s experience as an object lesson for king and people in the southern capital, Jerusalem, during the time of Assyrian control—indeed, turning his history into a manifesto for reform under Judah’s kings Hezekiah and Josiah. The Chronicler, however, barely noticed events in the north except where they impinged upon Judah, instead selecting mostly Judean vignettes and shaping them into a picture of how Judah should govern itself after the return from exile in Babylon.

Both historians had sources. The DH made reference to “the Book of the Annals of the Kings of Israel” or “Annals of the Kings of Judah.” The Chronicler used the DH and in addition cited “records” of prophets, such as Nathan, Shemaiah, and Iddo. These “records” consisted of traditional lore and stories, notably about the interaction of kings and prophets. Both historians selected radically, citing their sources as though anyone interested could readily consult them.

The historians composed their accounts late in the course of the story of ancient Israel, and they made the perspective of their own times plain for all to see. Prior to their particular outlooks, though, lies another perspective question: What were the social and political commitments that sustained earliest Israel’s sense of the meaning of life? Few matters are more deeply contested in biblical interpretation.

This chapter’s fundamental assumption is that a widely shared ideology lay deep within the ethos of the people called Israel—one that honored a national deity named Yahweh, who offered and guided the destiny and vocation of his people and who willed an essentially egalitarian social community. If not explicitly articulated in terms of “covenant,” this ideology was effectively covenantal. Based in divine gift, human gratitude, and mutual trust, the covenant demanded exclusive loyalty to the deity and human responsibility in communal relations. In such a perspective, government and the practice of community life mattered deeply. So did the conduct of relations with other nations. There could be differences over how leadership should be passed down and over what constituted appropriate loyalty and obedience to the state, but norms of justice and responsibility prevailed. Nor were these norms the exclusive possession of an elite and imposed on the populace. This was a shared ideology, exercising wide influence in the land, in both the north and the south. One carrier was the prophet, institutionalized in those circles of followers who arose to spread

his message; another carrier was the amorphous entity called the “people of the land” and the elders of the towns and villages.

As noted earlier, both the DH and Chronicler depended on source material. A few examples may help give a sense both of the character of these sources and of the way historians worked to highlight the ideologies they wished to convey.