The Oxford History of the Biblical World (45 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Architectural remains of the early monarchic era show a similar trend toward innovation and uniformity. Important new building techniques and structures can be dated to the Iron IIA period, especially in its latter stages during Solomon’s reign. According to 1 Kings 9.15–20, Solomon amassed labor forces “to build the house of the L

ORD

and his own house, the Millo and the wall of Jerusalem, Hazor, Megiddo, Gezer…, Lower Beth-horon, Baalath, Tamar in the wilderness, within the land, as well as all of Solomon’s storage cities, the cities for his chariots, the cities for his cavalry, and whatever Solomon desired to build, in Jerusalem, in Lebanon, and in all the land of his dominion.” Besides the capital, Jerusalem, this text mentions six cities as the focus of Solomonic regional urbanization, of which only the first three have been located with certainty. Excavations at those sites—Gezer, Megiddo, and Hazor—have provided a wealth of information about the public architecture of the early monarchy.

Anthropological assessments of the material features of monarchic rule stress that the erection of structures serving regional and national needs, rather than simply domestic or local ones, are part of emerging state systems. Fortifications and other large public buildings require expenditures of capital and labor beyond the resources of smaller-scale societies. Such projects have important economic and political functions, as well as less tangible symbolic and psychological ones. They contribute to the royal administration of national territory, while also signifying the power of the king. Urban development at Gezer, Megiddo, and Hazor thus constitutes archaeological data reflecting royal administration.

A striking uniformity in public architecture appears at Gezer, Megiddo, and Hazor in the early monarchy. The dating and interpretation of the public structures at these three sites are still debated among archaeologists, but attributing them to the period of Solomon enjoys wide support. Fortification walls in the Iron Age were of two types: the solid wall, usually 2.5 to 4.5 meters (8–15 feet) thick, and the casemate wall. The latter consisted of two parallel walls, the inner usually less substantial than the outer, which averaged 1 to 1.5 meters (3–4.5 feet) wide, and the distance between the two walls varying between 1.5 and 4 meters (4.5–13 feet). The two walls are linked by cross-walls; the rooms thus formed in the wall could be used for storage. Sometimes casemates form part of the adjacent houses, suggesting that this type arose when the outer walls of a series of houses were packed tightly around the perimeter of a site, forming a defensive structure. Whatever their origin, casemate walls became

rare after the tenth century. Their nearly simultaneous appearance at Gezer, Hazor, and probably Megiddo can be linked to Solomonic building activity, as can their presence at other urban sites newly emerging or reemerging on the Palestinian landscape in the tenth century.

The similarity in casemate wall construction of the second half of the tenth century is also evident in the gateways associated with those walls. The typical city gate consisted of four to six chambers, two or three on each side of the opening and projecting inward from the line of the wall. Gezer, Megiddo, and Hazor all feature six-chambered gates that are close enough in size and proportion to indicate a common architectural plan, with variations for local conditions. The façades of all three gates included projecting towers, and the width of the central passage was exactly the same—4.20 meters (13 feet 10 inches)—at each site. The gates of the major urban sites of the tenth century were constructed with evenly dressed stone blocks known as ashlars. More costly than the roughly trimmed field stones used for most buildings of the period, these blocks occur in formal buildings—palaces and shrines—at sites that, by virtue of their strategic locations, also served as regional royal cities. The formal architectural style of these buildings often included the earliest use of a particular kind of capital, called proto-Ionic (or proto-Aeolic) because it seems to be the prototype of the double volute Ionic capital of classical Greek architecture. Its curved volutes have their origin in the palm tree motif ubiquitous in ancient Near Eastern art. More than thirty-five such capitals have been discovered in Palestine, all at six or seven urban centers. The earliest two come from tenth-century Megiddo.

The high quality and uniformity of these features of the monumental architecture of the tenth century represent a building style that may have been designed in the United Monarchy by an unknown royal architect. It became popular thereafter in both kingdoms of the divided monarchy, as well as at neighboring Phoenician and Philistine sites. Some architectural historians suggest an Israelite origin for these fine Iron Age construction techniques and embellishments; others point to precursors in eastern Mediterranean culture at the end of the Late Bronze Age. Whatever their origin, their presence in the fortifications and palaces of regional centers is evidence of how the centralized government housed and protected the officials who carried out state policies.

Another kind of large building at several urban centers provides further evidence of state economic and political policies. These large rectangular structures, as big as 11 × 22 meters (35 feet 9 inches × 71 feet 6 inches), are subdivided into three internal longitudinal sections by two rows of internal columns running the length of the building. The prominence of the columns led archaeologists to call them “pillared buildings,” a fortunate designation in light of a controversy over their function: were they barracks, stables, or storehouses? Whatever their function, their origin in tenth-century royal cities can be related to political centralization—to the stationing of cavalry units in strategic cities (see 1 Kings 9.19), to the provisioning of officials loyal to the crown, or to the storage of materials being exchanged on the trade routes of the early state.

The urban architecture of Iron IIA was distinctive, as were the cities themselves. The preceding Iron I period saw deurbanization throughout Palestine. The rise of a state system in the tenth century

BCE

coincided with an urban revival within the

boundaries of the Israelite national territory. Most of the new urban centers were built on the sites of the old Bronze Age cities, although a few represent the continuation of Iron I village sites. The Iron II cities in some ways continue the Bronze Age urban traditions in their layout and location. But differences in size and in internal building types are indicative of a nation-state, rather than of the autonomous city-states of the Bronze Age.

As a whole, the Iron IIA cities—even major royal centers such as Gezer, Hazor, and Megiddo—are smaller than their Bronze Age precursors. Other cities were even smaller, with differing layouts and building types, and often they lacked fortifications or other prominent public buildings. With their dwellings crowded together in irregular fashion, many were villages grown large. Thus they differ in character from most Bronze Age urban sites, which were relatively independent political units, each featuring buildings that served the economic, military, royal, religious, and residential functions of a self-governing entity. Iron IIA cities, smaller and less complex, were part of a centralized state, with many governing functions reserved to the capital city or regional centers. The presence of a national state effected a new mode of urban existence.

One other feature of the royal cities mentioned in 1 Kings 9 is salient. The three cities that have been only tentatively identified seem to be located at strategic locations: Beth-horon, commanding the major access to Jerusalem from the north; and Baalath and Tamar, probably situated at the southern and southeastern borders of the kingdom. The three known sites mentioned in 1 Kings 9 are especially well placed. Gezer occupied one of the most important crossroads in ancient Palestine, guarding the place where the ascent to Jerusalem and other highland sites branches off from the major north-south coastal route, the “Way of the Sea.” Thus it protected southern trade routes and was also critical to the defense of Israel’s southwestern border, on the edge of lands still controlled by Philistines or sought by Egypt. Megiddo had a similar strategic importance because of its location near the intersection of the “Way of the Sea” with routes through the Jezreel Valley toward the east. Finally, Hazor commanded a strategic position at the junction of the main north-south highland route, connecting northern Palestine with the Phoenician coast and with the east-west highway extending toward Damascus.

It is no coincidence that these three cities occupied the three main intersections of the historic trading routes of the eastern Mediterranean. In addition to serving as regional centers, they were fortified and equipped with the administrative machinery and appropriate large-scale buildings to secure international trade in the Solomonic period. Whether this trade had already begun in Davidic times is difficult to ascertain. Most likely, foreign conquests and tribute provided the luxury items and other materials not available locally for the newly formed state and its bureaucrats from the beginning of the monarchy. Still, the cessation of warfare during Solomonic rule meant an increase in international trade connections during the middle to late tenth century. The brief flowering of central Negeb highland settlements in that period belongs to the same picture of commercial internationalism.

Other material remains also give evidence of a flourishing foreign trade. Imported wares, absent from the limited ceramic assemblages of the Iron I period, begin to appear in large quantities in the tenth century. Most prominent of these is the so-called

Cypro-Phoenician ware, a designation for fine or luxury vessels usually covered with a red slip and decorated with black concentric circles. Cypro-Phoenician ceramic vessels from abroad fed into an internal distribution network comprehensive enough to ensure their wide availability. The prosperous trading cities of the Phoenician coast, the source of these wares, also provided materials and technological expertise for building projects associated with Solomonic if not Davidic rule (see 2 Sam. 5.11; 1 Kings 5.1–12; see also 1 Chron. 22.3–4).

Iron objects, also indicative of international trade, appear in significant numbers for the first time in the tenth century. Indeed, twice as many iron artifacts have been recovered from Iron IIA contexts as from Iron I sites. Only in the tenth century did iron begin to play a significant role in political, economic, and military aspects of Israelite life. Its greatly increased use in weaponry, in tools for expanded agricultural activity, and in prestige items met various needs of the early monarchy.

The availability of iron, Phoenician pottery, and other imported goods depended for the most part on overland trade routes secured by the regional royal cities and the southern Negeb outposts. But maritime activity played its role in early monarchic international trade. The Philistine coastal city at Tell Qasile, probably destroyed by Davidic forces, became an Israelite port city, as did other contemporary sites on the Mediterranean. One of them, Tel Dor at the foot of Mount Carmel, was a Phoenician colony in the eleventh century. By the late eleventh century and then in the tenth, it became Israel’s leading harbor town, facilitating trade with Phoenicia and Cyprus. Other sea trade toward the south is known only from texts, notably the claim that Solomon built a fleet of ships to sail south from Ezion-geber at the Red Sea to acquire precious items, such as the highly valued incense, spices, rare woods, and gemstones of South Arabia and East Africa (see 1 Kings 9.26–28; 10.11–13). Archival records of Assyrian trade and its commodities from periods both earlier and later than the tenth century attest to the long history of trade in these items. Monarchic Israel had every reason to participate in that trade by southern sea routes connecting with overland caravans.

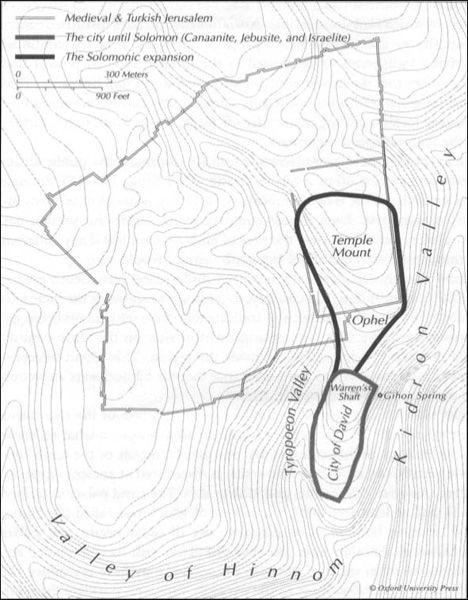

A major impetus for seeking secure routes and a lucrative international trade stemmed from the special needs and strategies of the state system’s urban nerve center, its capital. Saul is said to have ruled from Gibeah in Benjamin, although the biblical texts associating him with that site (probably Tell el-Ful just north of Jerusalem) are beset with difficulties. David first established his power base at Hebron but ultimately moved it to the city forever associated with his name: Jerusalem, the core of which was known as “the city of David” (2 Sam. 5.7). Whether David acquired Jerusalem by conquering its Jebusite inhabitants or through negotiation with them is uncertain. But the strategic brilliance in establishing a capital city outside the traditional areas of any existing tribal groups is clear: Jerusalem and its public buildings were a unifying factor in the early monarchy.

Archaeological evidence for the royal and administrative capital of the new monarchy is disconcertingly poor, especially in comparison with the recovery of so much from the regional centers of Solomon’s day. After more than a century and a half of archaeological excavation of the city of David, virtually no structural remains of the tenth century can be identified securely. Even the monumental “stepped stone structure,” for decades thought to be part of Davidic construction activity, has recently

been dated to the end of the Late Bronze Age (although it is likely to have been reused during the Iron IIA period as a retaining wall for the royal precincts built then). The same is true for “Warren’s Shaft,” a subterranean water channel at first identified with the “water shaft” mentioned in 2 Samuel 5.8 in connection with the Davidic capture of Jerusalem; some archaeologists now date it later than Iron IIA. Only fragmentary walls and scattered artifacts, none of which elicit images of the monumentality and grandeur of what David and Solomon are said to have constructed in Jerusalem (2 Sam. 5.9; 2 Kings 5–7), incontrovertibly belong to the period of the early monarchy.