The Oxford History of the Biblical World (46 page)

Read The Oxford History of the Biblical World Online

Authors: Michael D. Coogan

Jerusalem in the Time of David and Solomon

Yet the biblical record of monumental architecture in Jerusalem is not fictitious, and the discrepancy between textual records and material remains should not be used to discredit the former. The very importance of the city and its public buildings led

to the obliteration of the earliest Israelite structures. For thousands of years successive rebuildings, many of which sank foundations down to bedrock, have disturbed earlier remains. The sanctity of the temple-palace precinct especially attracted continual construction activity. Indigenous kings as well as the foreign imperial powers that controlled the city often tore down and built anew its most important buildings. That three postbiblical religious traditions—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—have vied for position at sacred locales, putting many sites off-limits for excavation, has further contributed to the archaeological nightmare.

Jerusalem’s ancient conquerors, moreover, routinely destroyed the public structures of the enemy and carried off as spoils its wealth (see 2 Kings 25.8–17). Because public buildings symbolized the state, demolishing or taking possession of them invariably followed a conquest. Even if one could excavate under the present-day shrines and holy places, some right over the sites of ancient ones, few if any coherent traces of the monumental architecture of the tenth century would turn up.

A different kind of archaeological data, however, underscores Jerusalem’s pivotal role. Surveys in the eastern Judean hill country, in addition to showing the increased settlement density of the Iron IIA period, also indicate that these settlements belonged to a more extensive territorial unit. The arrangement of sites on the tenth-century landscape points to a center—Jerusalem—outside the region. This recent interpretation of settlement patterns provides some assurance that the biblical texts’ depiction of Jerusalem as national center is rooted in reality.

Finally, we can test details recorded in the biblical description of the two major buildings in the capital—the Temple and the adjacent palace—against what we know of construction technology, architectural styles, and artistic motifs of the tenth century

BCE

. All have parallels in structures and artifacts discovered at ancient Egyptian, Phoenician, Syrian, Assyrian, Canaanite, and Hittite sites. The royal palace described in 1 Kings 7.1–11 had at least five units, the largest of which was called the House of the Forest of Lebanon because of its extensive use of cedar beams and pillars imported from Lebanon. Another unit, the Hall of Pillars, with its colonnaded entryway and its access to other units of the palace complex, may have resembled the Near Eastern

bit-hilani

structures. Most of the parallels, however, postdate the tenth century, a “dark age” in art and architecture because of the decline of the historic centers of political power in that period. This leaves Israel, with its reported construction of an extraordinary temple-palace complex in Jerusalem, as a trendsetter in the material world of its day. Ancient Israel is best known in postbiblical religious tradition for its spiritual and literary contributions, for its wisdom documents and prophetic calls for justice. But for one brief period in the millennium or so of its history it may have taken the lead in artistic creativity.

The military, techno-environmental, and demographic factors leading to state formation in early monarchic Israel, along with the spread of new settlements and the proliferation of public works, inevitably meant changes in the patterns of local leadership and in the relatively equal access to resources characteristic of the preceding Iron I period. Village, clan, or tribal elders lacked the supratribal power necessary to establish and equip a successful army, to move goods and people, and to embark on

the monumental construction projects necessary for the administrative structures of the emergent state’s extended territory. The archaeological record leaves no direct trace of the different levels of human activity and status connected with new sociopolitical arrangements. Thus scattered clues in the biblical narrative are important, as are social-science models, if used cautiously.

Most of the scarce biblical information about the earliest decades of the monarchy concerns military operations. We learn that Saul created a standing army (1 Sam. 13.2) under his direct command, but presumably with high-ranking officers in addition to his own son Jonathan and his cousin Abner (1 Sam. 14.50). He also seems to have appointed a priestly officer (1 Sam. 14.3, 18), a supervisor for his staff (1 Sam. 22.9), and someone to be in charge of his pasturages (1 Sam. 21.7). These textual references to administrative positions indicate a small nucleus of state officials. With a relatively tiny capital at Gibeah and a focus on warfare, there would have been little time, need, or resources for complex organizational development. But Saul’s military successes, and then David’s, ultimately did necessitate organizational complexity. At the same time, victory in warfare, with spoils and tribute, provided an economic base for specialists and workers in the overlapping domains of judicial, religious, commercial, diplomatic, and constructional activities.

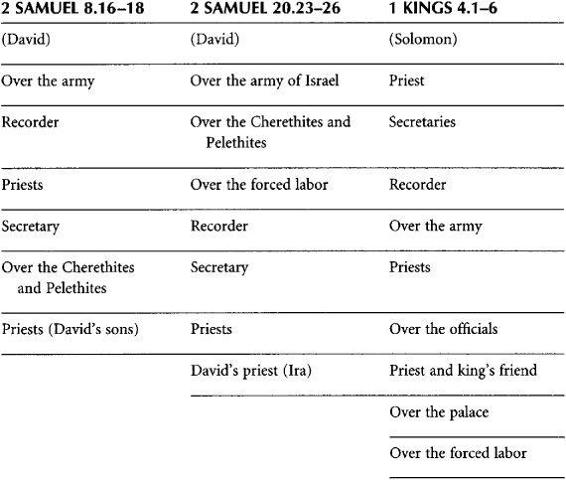

As might be expected for a king who ruled longer than Saul and whose reign eventually saw the cessation of conflict, David expanded and systematized his predecessor’s rudimentary administrative structures. The most direct evidence for the organization of the new state under David and then Solomon comes from three lists of high officials given in 2 Samuel and 1 Kings. (See

table 5.2

for the positions listed, in the order given in the texts.) The second of the two listings for David, presumably dating later in his reign than the first, indicates the adjustments he made as he gained experience in royal office. The most significant are a doubling of military officials; a shift from David’s sons to Ira of the post of a palace or Jerusalem priestly officer, the second priestly official in both lists; and the addition of an overseer for the labor forces.

The double set of military officers—one commanding the army, presumably an Israelite muster, and the other in charge of the Cherethites and Pelethites, two foreign mercenary units—reflects the importance of the fundamental source of royal power: the coercive strength of the military. The two types of military forces can be related to the king’s efforts to maintain his troops’ allegiance. The mercenaries, sustained and supported away from home by the crown, served the king directly and were inherently well controlled by their commander. A standing army is another story. The books of Samuel mention the king distributing spoils of war (1 Sam. 22.7; 30.21–25; see also 1 Sam. 17.25), an act meant to help secure the army’s loyalty. Another important aspect of the army and its faithfulness is that its leadership core consisted, for Saul, of fellow Benjaminites (1 Sam. 13.2; 22.7), and for David, fellow Judeans (1 Sam. 22.1–2). Likewise, Judeans in general, and not just those who served as soldiers, benefited materially from the successes of their kinsman David (1 Sam. 30.26–30; see also 2 Sam. 19.42; 20.2). Although David was commander in chief, he appointed “cabinet-level” chiefs of staff to maintain tight control of his military power base.

The double set of priestly administrators reflects another crucial aspect of royal

control. Royal rule depended in part on priestly groups stationed at shrines throughout the kingdom. Their appointment, perhaps accompanied by personal land grants, was from the crown and thus ensured loyalty to the throne. With the royal and ritual governments inextricably linked, priestly officials had more to do than simply perform ritual acts. Their business also included communications, adjudications, and the collection of revenues (in the form of offerings), although these functions may have overlapped with traditional procedures under the control of village and tribal elders. The network of priestly officials was closely linked to the redistribution of goods and thus deserved high-level government supervision.

Table 5.2 Officials under David and Solomon

Finally, the second Davidic list of officials contains an officer not found on the first list: a labor supervisor. Military success brought spoils of war, which filled the royal and priestly coffers (see especially 2 Sam. 8.7–12 and 12.30, and also 1 Sam. 15.9 and 27.9) and secured the loyalty of the army and key officials; and it also brought war captives into the kingdom. According to the narratives, foreign servitors came from Ammon, Moab, and Edom, as well as from the various Aramean cities that David encountered in his campaigns to the northeast (2 Sam. 8.2–14; 12.31). These captives constituted a workforce, with their own chief administrator, for the building projects initiated by David (2 Sam. 5.9, 11; 12.31; see also 1 Chron. 22.2).

The massive public works of the early monarchy are attributed to Solomon and were certainly completed during his reign. Yet some biblical texts suggest that Davidic military operations brought two important resources: capital, from spoils and tribute; and labor, from war captives. The local economy alone could not have supported such projects without severe deprivations to the indigenous subsistence farmers, nor would local residents endure the hardship of construction-gang work with much enthusiasm. Thus the wealth and labor acquired through war provided the human and fiscal resources for erecting the nation-state’s material structures. It would be a stretch to claim imperial control in the tenth century for the Jerusalem-based monarchy. Yet the small states or city-states between Palestine and Assyria, which normally paid tribute to one or another of the Mesopotamian states or to Egypt, could well have directed such payments to Jerusalem during the ascendancy of Davidic rule and the weakness of the traditional powers.

The monumental building projects of the early monarchy were crucial to the new regime. Such projects enhanced the image and status of the ruler and his bureaucracy. They won support from the newly appointed officials, or clients, whose loyalty depended on getting their share in the riches and on their access to the lifestyle of the royal court. Finally, monumental structures functioned as visual propaganda, announcing to neighbors that Israel had the military might to secure the resources to build them—and thus to demand the continued flow of tribute to the new capital. In such ways, monumental building projects, by integrating resources and labor, signified the emergence of a state system. At the same time they signaled the state’s coercive potential.

Other than the lists of David’s cabinet in 2 Samuel 8 and 20, little can be gleaned from available sources about the administrative structure of the kingdom. The governing class—courtiers, officials, generals, wealthy merchants and landowners, priestly leaders—constituted only a tiny fraction of the total population. The biblical texts concerning the monarchy contain a strong tradition of the elders and “all the people” having a voice in governance, suggesting that the Israelite monarchy was not a strongly authoritarian regime—not an “oriental despotism” such as some social scientists have modeled. Rather, it was more a participatory monarchy, with many royal decisions presumably both limited and directed by consultation with wider popular interests.

The advent of Solomonic rule, not surprisingly, brought in its wake a more elaborate set of bureaucratic functions. The passages in 1 Kings 4.7–19 and 27–28 describing the twelve officials “who provided food for the king and his household” (each for one month of the year) indicate new administrative hierarchies. This list of officers and their regions partly approximates existing tribal units but in other places diverges from them. Indeed, the list is full of places and names that resist conclusive identification. The known places also are irregularly scattered, and there are overlaps. Thus it is unlikely that, in establishing this set of officials, Solomon was setting up new administrative districts in order to break down existing tribal boundaries and thus tribal loyalties. It is more useful to focus on the functions of the officials in the list.

The twelve officials provisioned the royal establishment, and they supplied fodder for the royal horses. These officers may have served as a rudimentary tax-collecting

organization, each charged with collecting in his district sufficient foodstuffs for the court and its steeds. But at least some taxation was channeled through the priestly hierarchies. Another possibility for these officials and the strange topography of their bailiwicks is that they managed crown properties or plantations—lands confiscated or captured by David from pockets of non-Israelite settlements. This explanation accounts for the striking absence of an official in Judah. The New Revised Standard Version, with several Greek manuscripts, supplies “of Judah” at the end of 1 Kings 4.19; but the Hebrew omits reference to Judah. Presumably, no royal estates in Judah were meant to supply provisions for the court. This fits David’s policy of favoring his own tribe with the fruits—lands as well as goods—of his military accomplishments.