The Oxford History of World Cinema (12 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

profits, which put the industry on a more stable footing. In most countries, early cinemas

held fairly small audiences, and profits depended upon a rapid turnover, necessitating

short programmes and frequent changes of fare. This situation encouraged producers to

make short, standardized films to meet the constant demand. This demand was enhanced

through the construction of a star system patterned after the theatrical model which

guaranteed the steady loyalty of the newly emerging mass audience.

The films of this period, often referred to as the 'cinema of narrative integration', no

longer relied upon viewers' extra-textual knowledge but rather employed cinematic

conventions to create internally coherent narratives. The average film reached a standard

length of a 1000-foot reel and ran for about fifteen minutes, although the so-called 'feature

film', running an hour or more, also made its first appearance during these years. In

general, the emergence of the 'cinema of narrative integration' coincided with the cinema's

move toward the cultural mainstream and its establishment as the first truly mass

medium. Film companies responded to pressures from state and civic organizations with

internal censorship schemes and other strategies that gained both films and film industry a

degree of social respectability.

INDUSTRY

Before the First World War, European film industries dominated the international market,

with France, Italy, and Denmark the strongest exporters. From 60 to 70 per cent of all the

films imported into the United States and Europe were French. Pathé, the strongest of the

French studios, had been forced into aggressive expansion by the relatively small

domestic demand. It established offices in major cities around the world, supplemented

them with travelling salesmen who sold films and equipment, and, as a result, dominated

the market in countries that could support only one film company.

US producers faced strong competition from European product within their own country

for, despite the proliferation of relatively successful motion picture manufacturers during

the transitional years, a high percentage of films screened in the USA still originated in

Europe. Pathé opened a US office in 1904, and by 1907 other foreign firms, British and

Italian among them, were entering the US market on a regular basis. Many of these

distributed their product through the Kleine Optical Company, the major importer of

foreign films into the United States during these years and a company that played a

prominent role in the transition to the longer feature film. In 1907 French firms,

particularly Pathé, controlled the American market, sharing it with other European

countries: of the 1,200 films released in the United States that year only about 400 were

domestic. The American film industry took note of this, and the trade press, established in

this year with Moving Picture World, often complained about the inferior quality of the

imports, criticizing films that dealt with contemporary topics for their narrative

incomprehensibility and, worse yet, un-American morals.

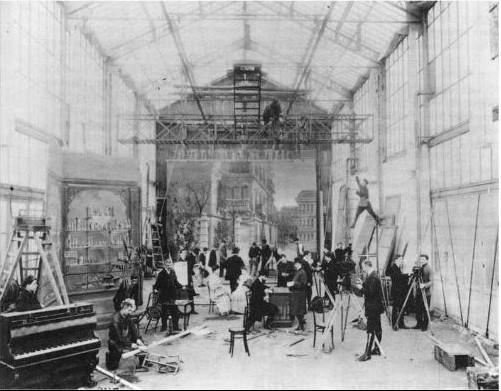

Pathé Frères' glass-topped studio at Vincennes, in 1906

Paradoxically, an earlier move to rationalize film distribution had resulted in a

maximization of profits, and as a result US manufacturers initially concentrated on the

domestic market. However, during these years they began a campaign of international

expansion that resulted in their being well placed to step into the number one position in

1914, when European film industries were reeling from the effects of the outbreak of war.

In 1907 Vitagraph became the first of the major US firms to establish overseas

distribution offices, and in 1909 other American producers established agencies in

London, which remained the European centre for American distribution until 1916. As a

result the British industry tended to concentrate on distribution and exhibition rather than

production, conceding American dominance in this area. American films constituted at

least half of those shown in Britain with Italian and French imports making up a

substantial portion of the rest. Germany, which also lacked a wellestablished industry of

its own, was the second most profitable market for American films. In the pre-war years,

however, American firms lacked the strength to compete with the powerful French and

Italian industries in their own countries. American films were distributed outside Europe,

but often not to the financial benefit of the production studios, who granted their British

distributors the rights not only to the British Isles and some Continental countries but to

British colonies as well.

During this period American film production took place mainly on the east coast, with an

outpost or two in Chicago and some companies making occasional forays to the west

coast and even to foreign locations. New York City was the headquarters of three of the

most important American companies: Edison had a studio in the Bronx, Vitagraph in

Brooklyn, and Biograph in the heart of the Manhattan show-business district on

Fourteenth Street. Other companies -- Solax and American Pathé among them -- had

studios across the Hudson in Fort Lee, New Jersey, which also served as a prime location

for many of the New York based companies. The Great Train Robbery ( Edison, 1903)

was only one of the many ' Jersey' Westerns shot in the vicinity. So over-used were certain

settings that a contemporary anecdote claimed that two companies once shot on either

side of a Fort Lee fence, sharing the same gate. Chicago served as headquarters for the

Selig and Essanay studios and for George Kleine's distribution company. Many studios

sent companies to California during the winter to take advantage of the superior locations

and shooting conditions, and Selig established a permanent studio there as early as 1909.

However, Los Angeles did not become the centre of the American industry until the First

World War.

Around 1903, the rise of film exchanges led to a crucial change in distribution practices,

which in turn created a radical change in modes of exhibition. The rise of permanent

venues, the nickelodeons that began to appear in numbers in 1906, made the film industry

a much more profitable business, encouraging others to join Edison, Biograph, and

Vitagraph as producers. Until this time the companies had sold rather than rented their

product to exhibitors. While this worked well for the travelling showmen who changed

their audiences from show to show, it acted against the establishment of permanent

exhibition sites. Dependent upon attracting repeat customers from the same

neighbourhood, permanent sites needed frequent changes of programme, and so long as

this involved having to purchase a large number of films it was prohibitively expensive.

The film exchanges solved this problem by buying the films from the manufacturers and

renting them to exhibitors, making permanent exhibition venues feasible and increasing

the medium's popularity. Improvements in projectors also facilitated the rise of permanent

venues, since exhibitors no longer had to rely on the production companies to supply

operators.

By 1908 the new medium was flourishing as never before, with the nickelodeons -- so

called because of their initial admission price of 5 cents -- springing up on every street

corner, and their urban patrons consumed by the 'nickel madness'. But the film industry

itself was in disarray. Neighbouring nickelodeons competed to rent the same films, or

actually rented the same films and competed for the same audience, while unscrupulous

exchanges were likely to supply exhibitors with films that had been in release so long that

rain-like scratches obscured the images. The exchanges and exhibitors now threatened to

wrest economic control of the industry from the producers. In addition civil authorities

and private reform groups, alarmed by the rapid growth of the new medium and its

perceived associations with workers and immigrants, began calling for film censorship

and regulation of the nickelodeons.

In late 1908, led by the Edison and Biograph companies, the producers attempted to

stabilize the industry and protect their own interests by forming the Motion Picture

Patents Company, or, as it was popularly known, the Trust. The Trust incorporated the

most important American producers and foreign firms distributing in the United States,

and was intended to exert oligopolistic control over the industry: Along with Edison and

Biograph, members included Vitagraph, the largest of American producers, Selig,

Essanay, Mélièlis, Pathé and Kleine, the Connecticutbased Kalem, and the Philadelphia-

based Lubin. The MPPC derived its powers from pooling patents on film stock, cameras,

and projectors, most of these owned by the Edison and Biograph companies. These two

had been engaged in lengthy legal disputes since Biograph was founded, but their

resolution now enabled them to claim the lion's share of the Trust's profits despite the fact

that they were at the time the two least prolific of the American production studios.

The members of the MPPC agreed to a standard price per foot for their films and

regularized the release of new films, each studio issuing from one to three reels a week on

a pre-established schedule. The MPPC did not attempt to exert its mastery through

outright ownership of distribution facilities and exhibition venues, but rather relied upon

exchanges' and exhibitors' needs for MPPC films and equipment that could only be

obtained by purchasing a licence. The licensed film exchanges had to lease films rather

than buy them outright, promising to return them after a certain period. Only licensed

exhibitors, supposedly vetted by the MPPC to ensure certain safety and sanitation

standards and required to pay weekly royalty on their patented projectors, could rent Trust

films from these exchanges. The Trust's arrangements had an immediate impact on the

market, freezing out much foreign competition so that by the end of 1909 imports

constituted less than half of released films, a percentage which continued to decline. The

prejudice against foreign films manifested in the Trust's exclusionary tactics may have

encouraged European studios to produce 'classic' subjects, literary adaptations and

historical epics for example, which were more acceptable to the American market. Pathé,

whose 1908 position as a primary supplier of product to American exchanges made it a

prominent member of the MPPC, pioneered this approach through the importation of

European high culture in the form of the

film d'art.

In 1910 the MPPC began business practices that presaged those of the Hollywood studios,

establishing a separate distribution arm, the General Film Company. This instituted

standing orders (an early form of block booking) and zoning requirements that prevented

unnecessary competition by prescribing which exhibitors within a certain geographical

area could show a film. Higher rental rates for newly released films, versus lower ones for

those that had been in circulation, encouraged the differentiation of first-run venues from

those showing the older and less expensive product, another hallmark of the coming

studio system.

The Motion Picture Patents Company survived as a legal entity until 1915, when it was

declared illegal under the

Asta Nielsen (1881-1972)

provisions of the Sherman Anti-Trust

Act, but even as early as 1912, several years before its

de jure

decline, the Trust had

de

facto

ceased to exert any significant control over the industry. Indeed, its members at this

point represented the old guard of the American film industry and many would cease to

exist soon after the court's unfavourable ruling. Their place was taken by the companies

of the nascent Hollywood moguls, many of whom had initially strengthened their position

in the industry through their resistance to the Trust's attempt to impose oligopolistic

control.

The MPPC's short-sighted plan to drive non-affiliated distributors and exhibitors out of

the business ironically sowed the seeds of its own destruction, for it gave rise to a

vigorous group of so-called 'independent' producers who supplied product to the many