The Oxford History of World Cinema (9 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

Edison's chief competitor. In 1897 Biograph also began to produce films but the Edison

Company effectively removed them from the market by entangling them in legal disputes

that remained unresolved until 1902.

At the turn of the century, Britain was the third important film-producing country. The

Edison Kinetoscope was first seen there in October 1894, but, because of Edison's

uncharacteristic failure to patent the device abroad, the Englishman R. W. Paul legally

copied the non-protected viewing machine and installed fifteen Kinetoscopes at the

exhibition hall at Earl's Court in London. When Edison belatedly sought to protect his

interests by cutting off the supply of films, Paul responded by going into production for

himself. In 1899, in conjunction with Birt Acres, who supplied the necessary technical

expertise, Paul opened the first British film studio, in north London. Another important

early British film-maker, Cecil Hepworth, built a studio in his London back garden in

1900. By 1902 Brighton had also become an important centre for British filmmaking with

two of the key members of the so-called 'Brighton school', George Albert Smith and

James Williamson, each operating a studio.

At this time, production, distribution, and exhibition practices differed markedly from

those that were to emerge during the transitional period; the film industry had not yet

attained the specialization and division of labour characteristic of large-scale capitalist

enterprises. Initially, production, distribution, and exhibition all remained the exclusive

province of the film manufacturers. The Lumière travelling cameramen used the

adaptable Cinématographe to shoot, develop, and project films, while American studios

such as Edison and Biograph usually supplied a projector, films, and even a projectionist

to the vaudeville houses that constituted the primary exhibition sites. Even with the rapid

emergence of independent travelling showmen in the United States, Britain, and

Germany, film distribution remained nonexistent. Producers sold rather than rented their

films; a practice which forestalled the development of permanent exhibition sites until the

second decade of the cinema's history.

As opposed to the strict division of labour and assemblyline practices that characterized

the Hollywood studios, production during this period was non-hierarchical and truly

collaborative. One of the most important early film 'directors' was Edwin S. Porter, who

had worked as a hired projectionist and then as an independent exhibitor. Porter joined the

Edison Company in 1900, first as a mechanic and then as head of production. Despite his

nominal position, Porter only controlled the technical aspects of filming and editing while

other Edison employees with theatrical experience took charge of directing the actors and

the mise-en-scène. Other American studios seem to have practised similar arrangements.

At Vitagraph, James Stuart Blackton and Albert Smith traded off their duties in front of

and behind the camera, one acting and the other shooting, and then reversing their roles

for the next film. In similar fashion, the members of the British Brighton school both

owned their production companies and functioned as cameramen. Georges Mélièlis, who

also owned his own company, did everything short of actually crank the camera, writing

the script, designing sets and costumes, devising trick effects, and often acting. The first

true 'director', in the modern sense of being responsible for all aspects of a film's actual

shooting, was probably introduced at the Biograph Company in 1903. The increased

production of fiction films required that one person have a sense of the film's narrative

development and of the connections between individual shots.

STYLE

As the emergence of the film director illustrates, changes in the film texts often

necessitated concomitant changes in the production process. But what did the earliest

films actually look like? Generally speaking, until 1907, filmmakers concerned

themselves with the individual shot, preserving the spatial aspects of the pro-filmic event

(the scene that takes place in front of the camera). They did not create temporal relations

or story causality by using cinematic interventions. They set the camera far enough from

the action to show the entire length of the human body as well as the spaces above the

head and below the feet. The camera was kept stationary, particularly in exterior shots,

with only occasional reframings to follow the action, and interventions through such

devices as editing or lighting were infrequent. This long-shot style is often referred to as a

tableau shot or a proscenium arch shot, the latter appellation stemming from the supposed

resemblance to the perspective an audience member would have from the front row centre

of a theatre. For this reason, pre-1907 film is often accused of being more theatrical than

cinematic, although the tableau style also replicates the perspective commonly seen in

such other period media as postcards and stereographs, and early film-makers derived

their inspiration as much from these and other visual texts as from the theatre.

Concerning themselves primarily with the individual shot, early film-makers tended not

to be overly interested in connections between shots; that is, editing. They did not

elaborate conventions for linking one shot to the next, for constructing a continuous linear

narrative, nor for keeping the viewer oriented in time and space. However, there were

some multi-shot films produced during this period, although rarely before 1902. In fact,

one can break the pre-1907 years into two subsidiary periods: 18941902/3, when the

majority of films consisted of one shot and were what we would today call

documentaries, known then, after the French usage, as actualities; and 19037, when the

multi-shot, fiction film gradually began to dominate, with simple narratives structuring

the temporal and causal relations between shots.

Many films of the 1894-1907 period seem strange from a modern perspective, since early

film-makers tended to be quite self-conscious in their narrative style, presenting their

films to the viewer as if they were carnival barkers touting their wares, rather than

disguising their presence through cinematic conventions as their successors were to do.

Unlike the omniscient narrators of realist novels and the Hollywood cinema, the early

cinema restricted narrative to a single point of view. For this reason, the early cinema

evoked a different relationship between the spectator and the screen, with viewers more

interested in the cinema as visual spectacle than as story-teller. So striking is the emphasis

upon spectacle during this period that many scholars have accepted Tom Gunning's

distinction between the early cinema as a 'cinema of attractions' and the transitional

cinema as a 'cinema of narrative integration' (

Gunning, 1986 ).

In the 'cinema of attractions', the viewer created meaning not through the interpretation of cinematic

conventions but through previously held information related to the pro-filmic event: ideas

of spatial coherence; the unity of an event with a recognizable beginning and end; and

knowledge of the subject-matter. During the transitional period, films began to require the

viewer to piece together a story predicated upon a knowledge of cinematic conventions.

1894-1902/3

The work of the two most important French producers of this period, the Lumières and

Mélièlis, provides an example of the textual conventions of the one-shot film. Perhaps the

most famous of the films that the Lumières showed in December 1895 is A Train Arriving

at a Station (

L'Arrivé d'un train en gare de la Ciotat

), which runs for about fifty seconds.

A stationary camera shows a train pulling into a station and the passengers disembarking,

the film continuing until most of them have exited the shot. Apocryphal tales persist that

the onrushing cinematic train so terrified audience members that they ducked under their

seats for protection. Another of the Lumières' films, Workers Leaving the Lumière

Factory (

Sortie d'usine

), had a less terrifying effect upon its audience. An eye-level

camera, set far enough back from the action to show not only the full-length figures of the

workers but the high garage-like door through which they exit, observes as the door opens

and disgorges the building's occupants, who disperse to either side of the frame. The film

ends roughly at the point when all the workers have left. Contemporary accounts indicate

that these and other Lumière films fascinated their audiences not by depicting riveting

events, but through incidental details that a modern viewer may find almost unnoticeable:

the gentle movement of the leaves in the background as a baby eats breakfast; the play of

light on the water as a boat leaves the harbour. The first film audiences did not demand to

be told stories, but found infinite fascination in the mere recording and reproduction of

the movement of animate and inanimate objects.

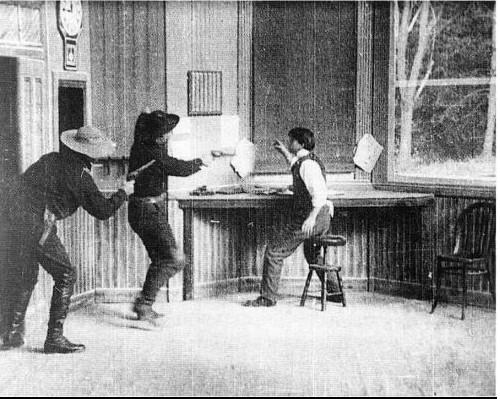

Edwin S. Porter's The Great Train Robbery ( 1903)

work, which depicted events that might have taken place even in the camera's absence,

this famous film stages action specifically for the moving pictures. A gardener waters a

lawn, a boy steps on the hose, halting the flow of water, the gardener peers questioningly

at the spigot, the boy removes his foot, and the restored stream of water douses the

gardener, who chases, catches, and spanks the boy. The film is shot with a stationary

camera in the standard tableau style of the period. At a key point in the action the boy,

trying to escape chastisement, exits the frame and the gardener follows, leaving the screen

blank for two seconds. A modern film-maker would pan the camera to follow the

characters or cut to the offscreen action, but the Lumières did neither, providing an

emblematic instance of the preservation of the space of the pro-filmic event taking

precedence over story causality or temporality.

Unlike the Lumières, Georges Mélièlis always shot in his studio, staging action for the

camera, his films showing fantastical events that could not happen in 'real life'. Although

all Mélièlis's films conform to the standard period tableau style, they are also replete with

magical appearances and disappearances, achieved through what cinematographers call

'stop action', that is, stopping the camera, having the actor enter or exit the shot, and then

starting the camera again to create the illusion that a character has simply vanished or

materialized. Mélièlis's films have played a key part in film scholars' debates over the

supposed theatricality of early cinematic style. Whereas scholars had previously thought

that stop action effects required no editing and hence concluded that Méliès's films were

simply 'filmed theatre', examination of the actual negatives reveals that substitution

effects were, in fact, produced through splicing or editing. Mélièlis also manipulated the

image through the superimposition of one shot over another so that many of the films

represent space in a manner more reminiscent of photographic devices developed during

the nineteenth century than of the theatre. Films such as L'Homme orchestre (

The One-

Man Band,

1900) or Le Mélomane (

The Melomaniac,

1903) showcased the cinematic

multiplication of a single image (in these cases of Mélièlis himself) achieved through the

layering of one shot over another.

Despite this cinematic manipulation of the pro-filmic space, Mélièlis's films remain in

many ways excessively theatrical, presenting a story as if it were being performed on a

stage, a characteristic they have in common with many of the fiction films of the pre-1907

period. Not only does the camera replicate the proscenium arch perspective, but the films

stage their action in a shallow playing space between the painted flats and the front of the

'stage', and characters enter or exit either from the wings or through traps. Mélièlis

boasted, in a 1907 article, that his studio's shooting area replicated a theatrical stage

'constructed exactly like one in a theatre and fitted with trapdoors, scenery slots, and

uprights'.

For many years film theorists pointed to the Lumière and Mélièlis films as the originating