The Oxford History of World Cinema (63 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

was also an amateur photographer, Charles Magnusson, was offered the chance to join

Svenska Biografteatern, a company which had been formed at Kristianstad in February of

the year before. He had some success with a series of films synchronized with

gramophone recordings, and then moved on to dedicate his energies to productions which

reflected the themes and personalities of Swedish theatre. He was assisted in his task by

Gustaf 'Munk' Linden, the author of an ambitious and popular version of the historical

drama Regina von Emmeritz and King Gustaf II Adolf ( 1910), and by the first female

director in scandinavia, Anna Hofman-Uddgren, who was given per mission by August

Strindberg to adapt his plays Miss Julie and The Father for the screen. Both appeared in

1912. The modest success of these films and the growing competition from Denmark

induced the owners to transfer production to Stockholm, where a larger studio set could

be built and where the chain of cinemas throughout Sweden could be better co-ordinated.

Magnusson demanded and was given absolute control over the move. He planned the new

studios at Lidingö, near Kyrkviken, and acquired the support of a group of artists and

technicians who were to define the course of silent cinema in Sweden: Julius Jaenzon,

appointed chief cameraman and director of the studios at Lidingé; Georg af Klercker,

head of production and director; Victor Sjöström, 'the best director on the market today'

according to the magazine Scenisk Konst, 6-7 April 1912; and Mauritz Stiller, a Russian-

Jewish theatre actor and director whose uneven stage career had led him back and forth

between Sweden and Finland for many years. Magnusson himself directed a number of

films between 1909 and 1912, but he soon settled into a role as producer-patron, offering

his formidable intuition and energy in support of the most risky ideas put to him by his

directors, but also ensuring the collaboration of high-calibre intellectuals, such as Selma

Lagerlöf, whose novels were filmed by Stiller and Sjöström. In 1919 a new young

financier, Ivan Kreuger, appeared on the scene and engineered the merger of Magnusson's

company with its rival Film Scandia A/S to form a new company, Svenska Filmindustri.

New studios were built, new cinemas were opened, and old ones restored. By 1920

Svenska Filmindustri had become a world power, with subsidiaries across the globe. The

'golden age' of Swedish cinema, stretching from 1916 to 1921, was in part due to

Sweden's neutrality in the Great War. At a time when almost all the other great film

industries in Europe (including that of Denmark) were threatened by embargoes and

serious financial difficulties, Sweden continued to export films without hindrance, and, by

the same token, took full advantage of the drastic reduction in imports. However, even

these favourable conditions would have had little impact were it not for the creative

contribution of a number of exceptionally talented directors.

The first in chronological order -- before Stiller and Sjöström joined Svenska

Biografteatern -- was Georg af Klercker, whose films are characterized by an extreme

figurative precision, a meticulous attention to acting, and by a restrained and rigorous

reinterpretation of the canons of bourgeois drama, social realism, and the 'circus' genre,

initiated in Denmark by Robert Dinesen and Alfred Lind with the seminal De fire djævle

('The four devils', Kinografen, 1911) and characterized by sentimental plots, spectacular

clashes, and vendettas amongst riders and acrobats. After Dödsritten under cirkuskupolen

(The Last Performance, 1912), the company's first international success, Klercker moved

briefly to Denmark. He returned to Sweden on the invitation of a new company, F. V.

Hasselblad Fotografiska AB of Göteborg, for whom he directed twenty-eight films

between 1915 and 1917. One of the best was Förstadtprästen ('The suburban vicar', 1917),

the story of a priest working to help society's rejects, filmed on location in the poor

districts of Göteborg.

Mauritz Stiller ( 1883-1928) specialized in comedies with a carefully controlled pace and

a subtle vein of social satire which verged on the burlesque, in which the construction and

articulation of events took precedence over psychological analysis and description. Two

typical examples of his style are provided by Den moderna suffragetten ('The modern

suffragette', 1913) and Kärlek och journalistik ('Love and journalism', 1916). He moved

on with Thomas Graals bösta film (Wanted: A Film Actress, 1917) and Thomas Graals

bästa barn (Marriage à la mode, 1918) to a set of 'moral tales' marked by a disillusioned

perspective on the precarious nature of relations between the sexes and on the inconstancy

of passion. This tendency in Stiller's work reached a peak of cynicism and disrespect in

Erotikon (Just like a Man; also known as After We are Married or Bonds that Cheat,

1920), but is offset at the turn of the decade by his growing penchant for treatments of

themes such as ambition and guilt. Herr Arnes pengar (UK title: Snows of Destiny; US

title Sir Arne's Treasure, 1919) and Gösta Berlings saga (UK title: The Atonement of

Gösta Berling; US title: The Legend of Gösta Berling, 1923), both taken from novels by

Selma Lagerlöf, elaborate such themes with a figurative intensity and epic energy which

no director in Europe had thus far achieved. Gösta Berlings saga also introduced a

talented young actress, Greta Garbo, whose inseparable companion and mentor Stiller

was to become. Invited to Hollywood by Louis B. Mayer, Stiller insisted on bringing

Garbo with him; but whereas their departure from Sweden was the first step in her

meteoric rise to stardom, for Stiller it coincided with a creative crisis from which he never

recovered.

With the departure to America of Sjöström ( 1923), Stiller and Garbo ( 1925), the actor

Lars Hanson, and the Danish director Benjamin Christensen who had made his most

ambitious film in Sweden, the perturbing documentary drama Häxan (Witchcraft through

the Ages, 1921), Swedish cinema entered a phase of steep decline. Instead of deciding on

a renewal of the themes and styles which had brought them such glory, directors of not

negligible talent such as Gustaf Molander, John W. Brunius, and Gustaf Edgren were

forced to ape their conventions in a wan attempt to adapt characteristics of their national

cinema to the genres and narrative models of 1920s Hollywood. 'We can now say', wrote

Ture Dahlin in 1931 in L'Art cinématographique, 'that the great silent cinema of Sweden

is dead, dead and buried. . . . It would take a genius to resurrect it from its present, routine

state.'

The fiction films made in Sweden in the silent period are estimated to have been about

500 (including shorts synchronized with phonograph recordings). About 200 are at

present preserved at the Svenska Filminstitutet in Stockholm.

Bibliography

Engberg, Marguerite ( 1977). Dansk stumfilm.

Film in Norway ( 1979).

Forslund, Bengt ( 1988), Victor Sjoström: His Life and his Work.

Schiave bianche allo specchio: le otigini del cinema in Scandinavia (1896 1918), ( 1986).

Uusitalo, Kari ( 1975), 'Finnish Film Production (1904-1918)'.

Werner, Gösta ( 1970), Den svenska filmens historia.

Victor Sjöström (1879-1960)

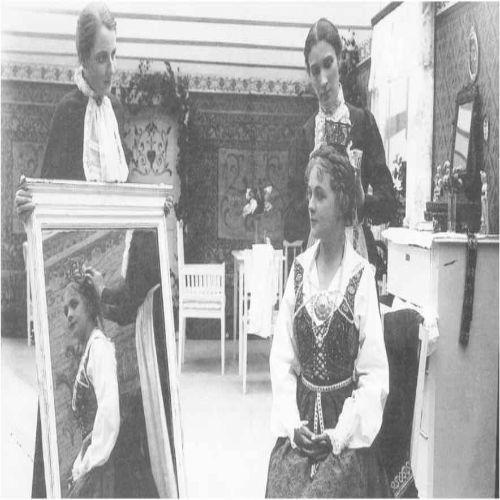

Tösen från Stormyrtorpet (The Girl from Stormy Croft, 1917).

In 1880 Sjöström's parents-a lumber merchant and a former actress - emigrated from

Sweden to the United States, taking their seven-month-old baby Victor with them. But the

mother soon died, and the son, to escape an unwelcome stepmother and an increasingly

authoritarian father, returned to Sweden, where he was brought up by his uncle Victor, an

actor at the Royal Dramatic Theatre in Stockholm. Fired by enthusiasm for the stage, the

young Victor also became an actor, and at the age of 20 was already renowned for his

sensitive performances and powerful stage presence.

In 1911 Charles Magnusson was busily reorganizing the Svenska Biografteatern film

studio, where he was head of production, aiming to give cinema more cultural legitimacy

by bringing in leading technical and artistic personnel from the best theatre companies in

Sweden. He hired the brilliant cameraman Julius Jaenzon (later to be responsible, for the

distinctive, look of many of Sjöström's most famous Swedish films), then in 1912 Mauritz

Stiller and, shortly afterwards, Victor Sjöström. Sjöström was by then running his own

theatre company in Malmö, but he eagerly accepted Magnusson's offer, driven (he wrote

later) 'by a youthful desire for adventure and a curiosity to try this new medium of which

then I did not have the slightest knowledge.'

After acting in a couple of films directed by Stiller, Sjöström turned to direction, making

his mark with the crisp realism applied to the controversial social drama

Ingeborg Holm ( 1913). But it was with Terje Vigen in 1917 that his creativity came into

full flower. The film shows a profound feeling for the Swedish landscape of his maternal

origins and achieves an intimate correspondence between natural events and the inner and

interpersonal conflicts of the characters. This symbiosis of inner and outer is even more

prominent in Berg-Ejvind och hans hustru ( The Outlaw and his Wife, 1918), the tragedy

of a couple seeking refuge - but finding death - in the mountains, in a vain attempt to

escape an unjust and oppressive society. 'Human love', said Sjöström, 'is the only answer

to fling in the face of a cruel nature.'

Partly out of her admiration fo Sjöström's films, the novelist Selma Lagerlöf had granted

all her film rights to Svenska Bio. Sjöström found in her work the ideal expression of the

active role played by nature in the destiny of characters torn between good and evil. In his

adaptation of The Sons off Ingmar (Ingmarssönerna, 1919) this vision finds expression in

a family saga of monumental scope. But it is at its most intense in The Phantom Carriage

(Körkarlen, 1921), a drama of the supernatural with a complex structure of interlaced

flashbacks, set on a New Year's Eve dominated by remorse and a desperated search for

redemption.

Swedish cinema had profited from the country's neutrality during the First World War to

make an impact on the European market and to challenge American supremacy. But after

the war it lost its precarious privileged position. With the industry in crisis, both Stiller

and Sjöström accepted offers to go to Hollywood. Sjöström arrived there in 1923, with a

contract from Goldwyn and his name changed to Seastrom. After some of the Lon Chaney

character - a scientist who decides to become a clown after a false friend has gone off not

only with his wife but with his most important research discovery.Triumphant in

Hollywood, Sjöström made The Divine Woman ( 1928) with his even more famous

compatriot, Greta Garbo. But more important and characteristic were two films with

Lillian Gish, The Scarlet Letter ( 1927) and The Wind (released in 1928). The former is a

free adaptation of Hawthorne's novel in which he was able to develop the theme of

intolerance and social isolation explored in Berg-Ejvind. Then, in The Wind he achieved

the ultimate tragic fusion of the violence of the elements and of human passions in a story

set in an isolated cabin in the midst of a windswept desert.A high point of the silent

aesthetic, The Wind was distributed in a synchronized version, allegedly with the ending

changed. Shortly after its release, Sjöström returned to Sweden. Although, in a letter to

Lillian Gish, he later referred to his time in the United States as 'perhaps the happiest days

of my life', it is possible that he felt apprehensive about his future role in Hollywood after

the coming of sound. After making one more film in Sweden and one in England, he went

back to his former career as an actor and in the 1940s became 'artistic adviser' to Svensk

Filmindustri. He acted in nineteen films - by Gustaf Molander, Arne Mattsson, and (most

notably) Ingmar Bergman, his protégés at Svensk Filmindustri; his final role was in

Bergman's Wild Strawberries ( 1957), a film which can be seen as a moving

autobiographical reflection of Sjöström's ideas on dreams and on the failings of mankind,

and an expression of his wonderment in face of the role of nature in shaping human