The Oxford History of World Cinema (65 page)

Read The Oxford History of World Cinema Online

Authors: Geoffrey Nowell-Smith

condemned as a 'decadent' by official Soviet histories, Yevgeny Frantsevich Bauer was

internationally rediscovered in 1989 as a major director. His work was informed by Art

Nouveau aesthetics and a Symbolist sensibility characteristic of the silver age of Russian

culture as a whole.

Born on 20 January 1867, into the family of a wellknown Austrian zither-player and his

Russian wife, Bauer kept Austrian citizenship, but was baptized into the Orthodox

religion.

Yevgeny Bauer attended (but never graduated from) the Moscow College of Painting,

Sculpture, and Architecture, and becam known as a set designer for operetta and farcical

comedies at Charles Aumont's winter garden Aquarium in Moscow, Mikhail Lentovsky's

vaudeville theatre, Hermitage, and the Theatre of Miniatures, Zon. During this time, he

also occasionally performed as an amateur actor. In 1912 he was hired as a contract set

designer for the Pathé Freres Moscow Department assisted by the future leading Soviet

set designer Alexei Utkin. In 1913 he designed sets for Drankov and Taldykin's super-

production The Tercentenary of the Rule of the House of Romanov, and later the same

year began his career as a director at Pathé's and Drankov and Taldykin's studios.

Bauer's unique directorial achievements were singled out as early as 1913, as being above

praise in their artistic taste and intuition - something rarely found in cinema. When Bauer

joined the Khanzhonkov company in January 1914, his fame was boosted by the

company's trade press; however, despite attempts to rank him among the biggest names of

contemporary theatre, Bauer's name remained largely unknown outside the circles of film

fans and film-makers.

Of the eighty-two films firmly accredited to Bauer, twenty-six remain - enough to

evaluate his original style in terms of set design, lighting, editing, and camera movement.

Referring to the unusually spacious interiors in Bauer's films, contemporaries noted their

affinity with Art Nouveau interior architecture associated in Russia with the name of

Fedor Shekhtel. Bauer's genius as a set designer reached its apex in 1916 in an ambitious

high-budget production A Life for a Life with lavish interiors filmed in very long shots

with overhead space sometimes twice the height of the characters. As a reviewer

remarked about these sets (designed in collaboration with Utkin), 'Bauer's school does not

recognize realism on the screen; but even if no one would live in such rooms . . . this still

produces an effect, a feeling, which is far better than the efforts of others who claim to be

directors.'

When in 1916 the craze for close-ups hit Russian filmmaking, many directors opposed it

on the grounds that the actors' faces covered the background space and thus diminished

the artistic effect of the settings. Although Bauer was excited by the narrative possibilities

provided by the close-up, it was not a simple change to make for a director whose

reputation (and, indeed, whose genius) was based on extraordinary set design.However,

despite Bauer's fame as a set designer, his achievements as a director were not limited to

this area. As early as 1913 his tracking shots display a sympathy towards the 'inner life' of

the characters rather than merely stressing the vastness of the décor. In marked contrast to

the Italian style (as evidenced for example in Pastrone's 1914Cabiria) in which the camera

scans the scene's space laterally without entering into it, Bauer's camera darts in and out,

mediating beteen the viewer and the actor.Bauer's interest in original lighting effects was

further encouraged in 1914 by analogous Danish and American experiments. This is how

the actor Iran Perestiani remembered Bauer's work with light: 'His scenery was alive,

mixing the monumental with the intimate. Next to a massive and heavy column - a

transparent web of tulle sheeting; the light plays over a brocade coverlet under the dark

arches of a low flat, over flowers, furs, crystal. A beam of light in his hands was an artist's

brush.'Bauer died of stagnant pneumonia on 9 June 1917, in a hospital in Crimea. There is

no way to tell what he would have achieved had he lived into the 1920s. Many of his

associates made impressive careers in the Soviet cinema: Bauer's permanent cameraman

Boris Zavelev shot Alexander Dovzhenko's Zvenigora ( 1927); Vasily Rakhal designed

sets for Sergei Eisenstein and Abram Room, and Bauer's youngest disciple Lev Kuleshov

was declared the founding father of the montage school.YURI TSIVIANSELECT

FILMOGRAPHY The Twilight of a Woman's Soul ( 1913); Child of the Big City / The

Girl from the Streets ( 1914); Silent Witnesses ( 1914); Daydreams / Deceived Dreams

( 1915); After Death / Motifs from Turgenev ( 1915); One Thousand and Second Ruse

( 1915); A Life for a Life / A Tear for Every Drop of Blood ( 1916); Dying Swan ( 1916);

Nelly Raintseva ( 1916); After Happiness ( 1917); The King of Paris ( 1917); The

Revolutionary ( 1917).

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Robinson, David ( 1990), 'Evgenii Bauer and the Cinema of Nikolai II', Sight and Sound,

Winter 1990.

Tsivian, Yuri ( 1989), "Evgenii Frantsevich Bauer".

The Soviet Union and the Russian émigrés

NATALIA NUSSINOVA

CINEMA AND THE REVOLUTION

The Soviet cinema was officially born on 27 August 1919, when Lenin signed the Council

of People's Commissars of the RSFSR Decree 'On the transfer of the photographic trade

and industry to Narkompros [The People's Commissariat of Education]', nationalizing

private film and photographic enterprises. But the struggle for power in film had already

begun in 1917, when film workers banded together in three professional organizations:

the OKO (a federation of distributors, exhibitors, and producers); the Union of Workers in

Cinematographic Art (creative workers -- the 'film aristocracy'); and the Union of

FilmTheatre Workers (the grass roots or proletariat, largely projectionists). The last of

these, asserting workers' control over cinemas and film enterprises, soon came to

determine the line taken by the Moscow and Petrograd Cinema Committees, which had

been set up in 1918 and had already begun nationalizing parts of the film industry. By the

end of 1918 the Petrograd Committee had nationalized sixty-four non-functioning

cinemas and two film studios abandoned by their previous owners, while in Moscow,

where most film enterprises were concentrated, a process of nationalization was carried

out between November 1918. and January 1920.

In this early phase only large companies were subject to nationalization, and the biggest

film studio (that of the Khanzhonkov Company) had no more than 100 people on its staff,

so during the first years of Soviet cinema private and state film companies coexisted.

Certain pre-revolutionary film companies (Drankov, Perski, Vengerov, and Khimera) went

out of business even before nationalization. The basis of Soviet film production was

therefore laid by half a dozen film enterprises, which after nationalization came under the

Photography and Film section of Narkompros. These were the former Khanzhonkov

studio (which became First Enterprise 'Goskino'), the Skobolev Committee (Second

Enterprise), Yermoliev (Third Enterprise), Rus (Fourth Enterprise), Taldykin's 'Era' (Fifth

Enterprise), and Kharitonov (Sixth Enterprise). New studios also began to be constructed,

of which the first was Sevzapkino in Petrograd (later Leningrad).

The process of restructuring continued throughout the 1920s. The former Khanzhonkov

and Yermoliev studios were merged in 1924, then in 1927 construction began in the

village of Potylikha outside Moscow of new premises for this studio, which it was

decided should become the largest in the country. Construction continued until the

beginning of the 1930s and in 1935 the new combined studio became known as Mosfilm.

Meanwhile private companies subsisted. The most resilient private owners adopted a

parallel policy of merging individual studios into larger enterprises, sometimes handing

over to Soviet power in so doing an element of their financial autonomy, sometimes

acquiring it in a new form. A prime example was Moisei Aleinikov, owner of Rus film

enterprise, which had been in existence since 1915. In 1923 Rus merged with the film

bureau Mezhrabpom and formed the company known as MezhrabpomRus, which was

reorganized in 1926 as a joint-stock company. Two years later it changed the composition

of its shareholders and reorganized itself again as MezhrabpomFilm, becoming part of the

German distribution organization Prometheus and obtaining from the Council of People's

Commissars special rights to export and import films. In this guise Mezhrabpom was to

play a central role in the diffusion of Soviet film in the west.

Pressure from film workers also continued to play a role in shaping the new situation. In

1924 a group of filmmakers, led by Sergei Eisenstein and Lev Kuleshov, came together in

Moscow to form the Association of Revolutionary Cinematography (ARC). The objective

of ARC (whose members came to include Vsevolod Pudovkin, Dziga Vertov, Grigory

Kozintsev, Leonid Trauberg, Georgi and Sergei Vasiliev, Sergei Yutkevich, Friedrich

Ermler, Esfir Shub, and many other leading film-makers) was to reinforce ideological

control over the creative process. Branches were formed in practically every studio, and

the organization had its own publications, including the weekly newspaper Kino and

(later) the magazines Sovietsky ekran and Kino i kultura. In 1929 ARC was renamed

ARRC (Association of Workers of Revolutionary Cinematography). At the end of the

decade, the All-Russian Association of Proletarian Writers (RAPP) had a strong influence

on ARRC, and a new aim was adopted of '100 per cent proletarian ideological film', as

part of the 'cultural revolution' being imposed throughout the arts.

During the 1920s regional studios came into being in the republics of the newly formed

USSR -- in the Ukraine, Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, and elsewhere. The

aim of these studios was to produce films relating to the local nationality in those areas,

and they enjoyed a certain measure of autonomy.

It was not long before the aim of concentrating and centralizing film production in order

to bring the cinema under social and state control led to the idea of establishing a single

national film industry. The first step in this direction came with the creation in December

1922 of the film enterprise Goskino, which was given a monopoly over film distribution.

In this form, Goskino turned out to be a useless bureaucracy, and it was axed at the

Twelfth Party Congress. A commission was set up to consider ways of 'uniting the film

industry on an all-Union basis' and merging all state film enterprises in each of the Union

republics in a single joint-stock society. The Thirteenth Party Congress in May 1924

confirmed this direction, adding the demand for reinforced ideological monitoring in

film-making and the appointment of 'tested Communists' to senior positions in the

industry. From December 1924 this became the role of Sovkino in the Russian Federation,

while similar organizations were set up in the Union republics -- VUFKU in the Ukraine,

AFKU in Azerbaijan, Bukhkino in Central Asia, and Goskinprom in Georgia. Sovkino

and its clones had a full monopoly of distribution, import, and export of films, and

gradually took over production functions as well. Althoulgh it managed to lose a lot of

money in its early years, the Sovkino system survived to the end of the decade without

significant alteration and provided the infrastructure for the great Soviet films of the late

silent period.

THE RUSSIAN ÉMIGRÉS

With the Revolution, the Russian cinema split into two camps. One section of the industry

remained in the USSR, zealously dedicated to destroying the pre-revolutionary

experience, and creating the art of a new epoch unencumbered by the heritage of a

bygone age. Another section went into exile, endeavouring to preserve abroad the cinema

which had come into being during the prerevolutionary years.

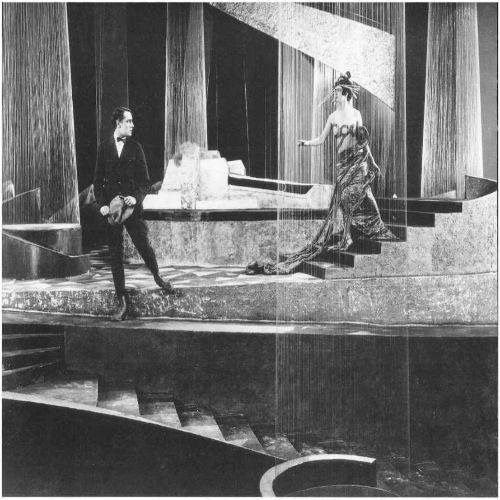

A scene from the science fantasy Aelita ( 1924), directed by the returning émigré Yakov

Protazanov, with constructivist sets by Exter

The emigration started with a group of film-makers who in the summer of 1918 had gone