The Pirate Queen (33 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

They returned to Greenland in the summer, following the opposite route up Labrador to Baffin Island, across the Davis Strait and south. They were wealthy now, loaded with timber and furs, and at first, perhaps, everyone expected the Icelandic brothers to follow, equally loaded down with goods. Eventually the story of the massacre leaked out and Leif discovered what FreydÃs had done. “I do not have the heart,” said Leif when he heard the news, “to punish my sister FreydÃs as she deserves.

But I prophesy that her descendants will never prosper.”

“And after that no one thought anything but ill of her and her family,” the writer of

The Greenlanders' Saga

concludes.

This story has, for a long time, intrigued and baffled me. Why would one of the leaders want half the expedition crew killed? Was it possible that a woman, even a bad-tempered Viking, would take an axe to five women she'd worked alongside for months? Even if they were slaves? How had this bloodthirsty tale made it into the Icelandic sagas, and did it have a purpose beyond its purported truth?

Although FreydÃs wasn't Icelandic herself, she was probably born here, and I hoped in Iceland, home of the sagas, to find some answers to my questions about this notorious woman. I most wanted to know why, given how far she ranged, she wasn't seen for the seafaring explorer she was. Although I could understand the financial reasons for her trip, I thought she must have had other reasonsâwanderlust, curiosity and a strong desire to prove herself fearlessâto impel her from the safety of home out into the almost unknown ocean.

I

N THE

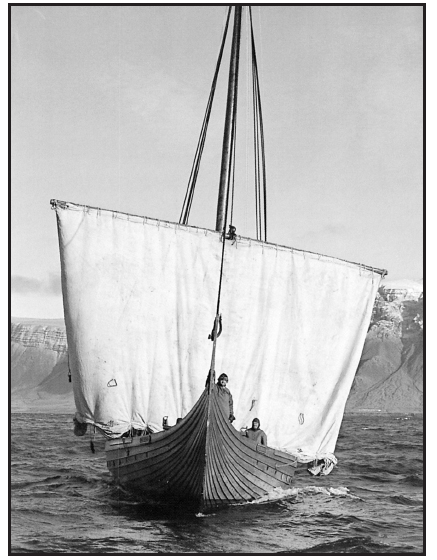

harbor of ReykjavÃk, on a glass-bright summer morning with the icy whip of the Arctic in the north wind, a Viking ship prepared to set off for a voyage to the New World. Clinker-built from pine and oak, the

Islendingur

's prow swept high up off the water, more like a sculpture than a boat. That sweeping prow and broad beam would keep it from foundering in the rough seas between here and VÃnland. The shallow draught would help it ride out gales as well as glide on and off shore. A single tall mast was placed amidships; from there the heavy square sail could be hoisted from the yard.

“Come onboard,” said Ellen Ingvadóttir, and I hopped over the side.

The

Islendingur

had a deck, unlike ships from the past, where the cargo had been stowed in the hull and covered with ox hides, and livestock jostled for room with three or four dozen people. On this upcoming voyage from Iceland across the North Atlantic to the New World there would be only nine people, all of whom would sleep in bunks. It wasn't luxurious, but compared to conditions in the Viking Age, it was extravagantly comfortable. Ellen showed me a small galley and a toilet secreted away. “I don't usually show people the toilet,” she said. “Most of the media have an unhealthy obsession with our elimination arrangements, especially mine.” She was to be the only woman on a crew captained by Gunnar Eggertsson, who'd built this ship himself about four years ago. It was a faithful replica of the Gokstad ship dated 900

A.D

., excavated in Norway, in 1880 and now displayed in an Oslo museum. They'd be setting off in about a week for Greenland and from there to Canada and down the eastern seaboard to Manhattan.

Six feet tall, large-boned, with a mature woman's figure, Ellen was bigger than a couple of the men on the ship, but still not quite someone you'd expect to find getting ready to cross the North Atlantic in a seventy-five-foot wooden sailing vessel. When I'd met her at her office, she'd looked every inch the successful woman professional: blond hair pulled back in a black bow from a strong, attractive face, big clip-on earrings, a flowing suit, and low heels. A certified court interpreter and translator, Ellen ran a translation bureau with a staff of eight. She was also head of Iceland's National Organization of Conservative Women (since one of their goals was to increase the number of women active in politics via participation in the Gender Equality Council, I could only surmise that an Icelandic conservative was different from one in, say, South Carolina). But in her youth Ellen had participated in the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, on the Icelandic swim team, and like most Icelanders, she was resilient and versatile. “In such a small country,” one Icelander had told me, “we don't have enough people to go around. So all of us have to wear many hats.” One of Ellen's hats included participating in this millennial voyage in honor of Leif EirÃksson's discovery of VÃnland in the year 1000.

“We'll be retracing the route of the Greenland and VÃnland

expeditions, stopping at something like twenty-four ports. There's a lot of PR involved, setting up contacts, translating, talking to the media; I'll be keeping the ship's log, too, in English, on our website. Naturally I'll be doing my share of the ship's tasks,” she said, glancing at the three men who had jumped off the

Islendingur

to have a smoke on the dock. “I'm really tired of being asked by people how it's going to be living with eight men in such close quarters for several months. We'll be busy. There will be a lot of work to do and no time to worry about appearances. Of course,” she added wryly, “somehow or other I'll have to pull myself together for the television cameras in port. I'm a little worried about the hair washing.”

I could sympathize. On this chill windy morning, I'd clamped the knit watch cap I'd bought in Orkney over my disheveled hair and wrapped my neck in a scratchy woolen scarf. I was wearing long underwear and a bulky Icelandic sweater under my green rain slicker. I'd felt like a large androgynous gnome making my way to Ellen's office. It was hard to be both elegant and warm on this trip. I could hardly imagine battling waves and storms only to come into foreign ports under camera surveillance.

The

Islendingur

smelled clean, of tar and wood oil and sawdust. Because of the wind, the ship was in motion even tied to the dock. I tried to imagine myself among forty to fifty people shoulder to shoulder on this rocking vessel, all our worldly goods piled around us: knives and scythes, barrels of water, sacks of feed and seeds, dried fish, whey; precious woven wool for sails and clothes, spindles and needles. I tried to imagine other ships around us, loading up as well with families hopeful and afraid. In the summer of the year 985, twenty-five oceangoing

knarrs

departed Iceland to help EirÃk the Red colonize

Greenland. Only fourteen of the vessels arrived in Greenland, the rest driven back or sunk by heavy seas.

Later colonists also suffered from foul weather: A girl called GudrÃd Thorbjarnardóttir set off from under the shadow of Snæfellsnes Mountain with her family in the spring of 997; they didn't reach Greenland until the end of October. Apparently GudrÃd didn't harbor terrible memories of the ocean journey; within a few years she was voyaging farther north up the coast of Greenland, to the Western Settlement, with her husband, Thorstein, EirÃk the Red's son. After his death she married the Icelandic trader Thorfinn Karlsefni and they decided to try their luck in VÃnland. That expedition probably lasted several years; with them came as many as a hundred Greenlanders and their slaves, in search of the rich resources Leif had described.

GudrÃd's sea journeys are told in

The VÃnland Sagas.

She and her husband Karlsefni spent two or three years in the New World, and GudrÃd gave birth to a son, Snorri. After clashing repeatedly with the natives, the colony sailed en masse back to Greenland; the following year GudrÃd and Karlsefni went on to Norway to sell their rich harvest of timber and furs. Already wealthy, Karlsefni was now even better off. He and GudrÃd returned to a farm in the north of Iceland. But GudrÃd's travels weren't over. After the death of her husbandâand no longer youngâshe set off on a pilgrimage to Rome, crossing first to Denmark, and then going overland from there. Other Icelandic women made the same voyage, it appears. In a register of medieval pilgrims at the Swiss monastery of Reichenau, a page devoted to Icelanders lists four women's names from the eleventh century, most likely highborn women who would have had companions and servants.

After centuries in which the most common image of a

Viking was a wild-eyed warrior with hairy legs, who wore a bronze helmet and wielded an axe, centuries in which the very word

Viking

meant “man” and the voyages to Greenland and the New World were perceived as male enterprises with Leif “the Lucky” EirÃksson as the single hero, quite recently a new figureâfemaleâhas entered the picture to become part of the myth of the Vikings' westward expansion. Even before arriving in Iceland, I'd come across GudrÃd's name in a brochure for a new translation of the complete Icelandic sagas.

In ReykjavÃk, I found that GudrÃd's star was definitely on the rise. A local playwright and director, Brynja Benediktsdóttir, had written a play about her life, and Jónas Kristjánsson, saga scholar, had recently published a novel. Gulli and Gudrún Bergmann, back on the Snæfellsnes Peninsula, had been working to have a statue of GudrÃd erected there, near her birthplace, and up in the north, in Glaumbær, where GudrÃd was said to have spent the remaining years of her life as an anchoress after returning from Rome, there was a monument. Even Ellen and crew had gotten on the bandwagon; they mentioned GudrÃd in their promotional material and Ellen planned to take the opportunity as the

Islendingur

came into port to talk up this seafaring woman to a public ignorant of Viking heroines.

But of FreydÃs EirÃksdóttir there was, oddly, not a word.

“I

T

'

S TIME

that GudrÃd was acknowledged,” said Jónas Kristjánsson to me a few hours later as we sat in a café in central ReykjavÃk. I was feeling a bit the worse for wear. After leaving Ellen, I'd ventured into a hair salon, removed my tight watch cap and asked for help. I didn't want to meet a manuscript specialist, professor emeritus, and novelist looking like a gnome.

The stylist had recommended something called Hár Hónnun (Hair Honey), which quivered in its plastic jar like a musical instrument from another planet. I thought it was a gel, but it was more like glue; my hair was now plastered down like sticky chunks of wood.

But Jónas treated me very courteously; I could see he was having trouble with his sparse hair today as well because of the furious cold wind. He combed it down carefully before ordering coffee for us, and bringing out a copy of a novel he'd written about GudrÃd Thorbjarnardóttir,

The Wide World.

Now retired from his long-held position as director of the Ãrni Magnússon Institute, which was built especially to house the old vellum books from Iceland's past, he was turning his energy to fiction.

Eventually I brought up the subject of FreydÃs EirÃksdóttir. Why didn't she get more recognition as a pioneering seafarer?

“Ah, FreydÃs EirÃksdóttir . . .” Jónas looked away.

It was a common reaction: an embarrassed laugh, a rolling of the eyes, a sigh. Earlier today Ellen Ingvadóttir had groaned when I mentioned FreydÃs, as I might if someone wanted to enthuse about what a strong role model for women Margaret Thatcher had been. The kindest description of FreydÃs I'd come across was “hot-headed.” Other sources were far more pejorative. “Arrogant” and “greedy” were two of the lesser epithets; “bloody” and “murderous” two of the worst.

“Who knows exactly what the truth is?” Jónas said when I pressed him about whether he believed that FreydÃs was really so evil. “The fact is we have only the sagas to go on and they were written between two and three centuries after the events. Perhaps FreydÃs had some reason to do what she did. Perhaps someone didn't like her.”

Perhaps it was a question of blame. After Jónas had

departed, I sat for a while longer in the café, reluctant to face the freezing wind. I took out my copy of

Women in the Viking Age

by Judith Jesch. Jesch is part of a new generation of Scandinavian scholars who have applied feminist theory to accepted history. She takes a cool view of the oft-made claim that women in the sagas were strong heroines: “Because the women of the sagas of Iceland are

not

portrayed primarily as objects of desire, many critics have been fooled into overlooking the stereotypic ways in which they are portrayed.”

In a section called “Iceland's Vengeful Housewives” Jesch dissects the image of the female inciter who appears in so many of the great family sagas. Unlike their mythic predecessors, the Valkyries, these literary women almost never employ violence themselves, either with fists or weapons. Instead, they use cruel jibes and threats to create situations in which their men, unable to stand being taunted any longer, break down and murder someone.