The Pirate Queen (34 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

Iceland in the thirteenth century, when the sagas were written down, was a country riven by blood feuds, the Sicily of the North. The democratic institution of the parliament with its lawgivers had almost collapsed. By 1235 civil war had broken out, and in 1262 the Icelanders submitted to the Norwegian crown. The lack of centralized authority had, while creating a more classless society, also resulted in family-enforced punishments and increasing civil disorder. In looking for someone to blame for the disintegration of their society into warring factions, the saga writers lit upon the not completely novel idea of pointing the finger at women. FreydÃs fits right into this scenario of women who whet, except that, not content merely to goad, she takes the axe into her own hands at the end to become a mass murderer.

P

LAYWRIGHT AND

director Brynja Benediktsdóttir was one of the only Icelanders I met willing to entertain a different view of FreydÃs. A few days after my coffee with Jónas, I walked over to Brynja's house for lunch. The rooms were dark mustard with wide-planked wooden floors; a lace-curtained window offered a view of the Tjörn, the small lake near the city's center. There was a shiny black grand piano, an antique four-poster bed in a corner, and a very random collection of chairs.

“My play,

The Saga of GudrÃd,

is based on both sagas, particularly

The Saga of EirÃk the Red.

That's the one with the most information about GudrÃd and her husband Karlsefni. One of the things I was most interested in writing about was the interaction between the colonists and the native population. You know, the reason that the VÃnland settlement failed was not lack of resources. The world climate was warmer then; there was plenty of everything, timber, game, fish, fruit, and they were in addition very resourceful people. But they had no concept of how to deal with a native population, the people they called

skrælings.

There had been no significant native population in either Iceland or Greenland when these countries were settled, so the encounters with the inhabitants [perhaps ancestors of the Mi'kmaq or the Innu] which had begun with some friendliness, quickly deteriorated into suspicion, attacks, and counterattacks. That's really the story of

The VÃnland Sagas,

the attempts and ultimate failure of the white settlers to understand and acknowledge the people already living there. It foretells the failure of the Europeans five hundred years later!”

At sixty, Brynja had been in theater most of her life. Her blond hair was short; her face composed and open. She had the

contented, busy air of a successful impresario. She showed me clippings from newspapers in Sweden and Ireland, where her play had been performed. Her favorite performances had been in Greenland. She patted an unusual necklace of carved bone on her chest, which had been given to her by Greenlanders.

Brynja saw GudrÃd and FreydÃs as mirror images. The purpose of putting FreydÃs beyond the pale was to raise GudrÃd's status. It was all about religion, about deconstructing Iceland's pagan past and assigning blame. “The descendants of GudrÃd were bishops, a long line of them. One of them was trying to put together a good Christian lineage to impress the Vatican. When the story of GudrÃd was written down, GudrÃd was elevated as Christian and quite devout. After she and Karlsefni returned to Iceland he died, and then she went off by herself on a pilgrimage by ship and foot to Rome. When she returned, she became a nun and an anchoress. FreydÃs, on the other hand, was a bastard and a pagan, and comparing the two women made GudrÃd look wonderful. Some scholars now think that part of the purpose of

The Saga of EirÃk the Red

was to elevate the courage and goodness of GudrÃd and Karlsefni so that her descendants might be canonized.”

I knew too little about the intricate belief systems of the pagan Norse to even guess what sort of heathen FreydÃs might have been. Would she have sacrificed animals at the shrine of Odin, or perhaps to Freya, the Norse goddess of fertility? Freya introduced divination to mortals, and her cult of followers, many of them women, included seers and foretellers. Freya was also known for bringing discord among the gods. But before Freya joined the complicated pantheon of Norse gods, and was relegated to a lesser position as female troublemaker, she'd been the Great Goddess herself. Freya. FreydÃs. Was this the reason

the churchmen who wrote down the sagas had it in for her?

Leaving Brynja's, I walked over to HallgrÃm's Church, where a statue of Leif EirÃksson towers over the square. Although it was presented to the city by a group of Americans in 1930, it embodies the centuries-long pride the Icelanders have taken in this native son (though he actually lived in Greenland most of his life). One of the reasons that Leif was called “the Lucky” was that he seems to have led a charmed life, and that's emphasized in the sagas. As charismatic as his father, Leif comes down to us a born leader. The stories of him reminded me a little of those told about Grace O'Malley. They had a certain prideful pleasure. Here was someone well respected, well remembered, and well loved, who reflected only good upon the race.

FreydÃs was no Grace O'Malley, but was she really Lizzie Borden? In

The Saga of EirÃk the Red,

the one Brynja had used as the basis for her play, there's no mention of FreydÃs as a psychopathic killer of her own sex. In that saga, FreydÃs barely appears, and seems to be on the same expedition to VÃnland as GudrÃd and Karlsefni. But her brief appearance is, in fact, heroic. When the Norse were attacked by the Indians, the male settlers ran off, but FreydÃs, heavily pregnant, stood her ground, calling to them, “Why do you flee from such pitiful wretches, brave men like you? You should be able to slaughter them like cattle. If I had weapons, I am sure I could fight better than any of you.” She snatched up a sword from a slain man and faced the

skrælings.

Pulling down her shift to show one of her breasts (possibly to indicate she was a woman), she slapped at it with the flat part of the sword and frightened the natives off.

What was the truth of the events so long ago in Greenland and VÃnland? Was FreydÃs a heroine or a murderer? What

happened to Finnbogi and Helgi and their followers? Perhaps one of the ships was no longer seaworthy enough for the return home, and the Greenlanders, under the direction of FreydÃs, did take the remaining ship and sail off, leaving the Icelanders behind. Perhaps when the two ships set a return course for Greenland after their stay in Straumfjord, the Icelanders didn't get back safely. Their absence gave rise to rumors; the rumors were pinned on FreydÃs. The Norse were a violent people; we can only speculate about events so long ago. The important thing

is

to speculate, to keep the possibilities open.

What continues to strike me about the legend of FreydÃs is what a closed book it is to many scholars and researchers, and how easily it's assumed she turned murderer. In fact, there's no other example in saga literature, replete as it is with women's jealousy, hatred, and goading, of a woman who kills in such an outright fashion. Whatever her accomplishments, however great her courage at masterminding an expedition to a distant shore and organizing life under difficult circumstances, it doesn't seem that FreydÃs could get her companions to like her, much less love her as they did Leif. I didn't find it easy to believe that FreydÃs had ordered all the Icelanders to be killed, much less that she'd hacked the Icelandic women to death with an axe, but I didn't have a problem believing she lacked an outgoing, lively personality that made men want to follow her anywhere.

Grace O'Malley, like Leif EirÃksson, had an innate gift of leadership, a trustworthiness and verve, a charm and power that made her sailors and warriors overlook and even celebrate her gender. FreydÃs was tough, but that toughness inspired hatred, not admiration, at least in the medieval churchmen who transcribed and reinterpreted Iceland's oral tradition. Many scholars now consider the sagas more fiction than truth, just as

much for what they say about medieval Christian belief as what they say about their pagan Viking forebears. But if the sagas are fiction, then why don't more scholars question the intent of the stories about FreydÃs?

I looked up at the statue of Leif's massive legs and barrel chest, the cloak swirling down his back, the helmeted head arrogantly tilted back, the gaze calm and lordly. He held the traditional double-headed, long-handled axe of the Vikings. In his hands it was a symbol, so expected as to seem unremarkable, of domination and confidence. It hardly even looked like a weapon meant to kill people, just an extension of his powerful body.

T

HE SILVER

river cut a swath through green meadows where horses grazed by the hundreds. North was open ocean, the Greenland Sea; yet the day had a fluted balminess. I was in the delta valley of Skagafjord, in the north of Iceland, a part of the country generally warmer in summer than ReykjavÃk. Not that it was tropical; it was more like Wyoming or Montana, an impression reinforced by the proliferation of Jeeps and trucks on the roads, and the lack of inhabitants. There were few villages in rural Iceland, and the convenience store attached to a gas station was the social hub. Most of the interior was lava or gravel desert, or glacier or mountain; the sparse pastures and farmlands clustered around the edges of the country, especially around large bays or deep fjords like this one. The farming population, though once much larger, had never been large enough or wealthy enough to create many towns with schools, churches, banks, and offices. Yet some of the farms had been social clusters in themselves, supporting and sheltering several dozen people.

Today I was visiting Glaumbær, an old farm now turned

into a museum. I didn't know which was more remarkable, being inside the warren of dark, dirt-floored rooms that seemed to be dug out of earth, the home of Mr. and Mrs. Badger and their children, or standing outside and watching how the grass rippled over the roof and the low sod walls, some set with glass windows. These turf farmhouses were built up from loaves of sod in horizontal rows, the sod placed on the diagonal in a herringbone pattern. Over the years the sod had hardened and the colors had softened. They were a ravishing marble of rose, burnt sienna, and yellow ochre. From a short distance, the rounded outside walls looked as if they'd been quarried in Italy.

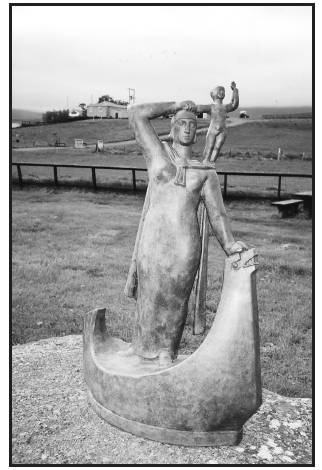

One of the reasons the buildings at Glaumbær had remained intact was that, although they were only one or two centuries old, they were built on land that was said to have been farmed by Thorfinn Karlsefni and GudrÃd Thorbjarnardóttir, and their son, Snorri. Not far from the farmhouse was a verdigris-weathered bronze statue, about two feet tall, on a rock. A woman stood on a ship, one hand on the upward-sweeping prow. With the other arm she hoisted a baby on her shoulder. He had the fully formed, small adult limbs of a medieval baby Jesus; uncradled and alert, he stood on his mother as if her shoulder were a crossbar on a mast.

I was glad to see GudrÃd honored, but what a curious, feminine memorial it was, small and maternal, so unlike the enormous statue of Leif in ReykjavÃk. GudrÃd's iconography was Madonna-like. Her potency was in having given birth to Snorri and a line of bishops, her rediscovered importance to Icelandic history seemed to lie in modesty, faith, and willingness to follow where her father and husbands led; though perhaps, on her own at the end, traveling to Rome, she'd finally known independence.

I sat down on the grass and began to sketch the small statue of GudrÃd. I remembered how two months ago, in Ireland, I'd tried to imagine my travels as

an thuras,

a counterclockwise journey around relics and sacred sites, with a ritual performed at each one. Over the weeks, I'd found a few historical traces of women's lives in the buildings where they'd lived. There were the dormitories of the herring lassies, the big houses built by Christian Robertson in Stromness, the dismantled croft house of Betty Mouat, the castles of Grace O'Malley. They were not exactly monuments or sacred sites, and I'd performed no rituals other than to take photographs. This statue of GudrÃd on a ship was the first marker I'd found specifically placed to recognize a woman's achievement as an explorer and seafarer. I used to think of statues as part of the vague background of city life, busts of forgotten city fathers and obscure poets hidden in park foliage, or bronze horses rearing up in traffic circles. But journeying with a historical purpose had made me look at how figures from the past, especially women, were remembered and how their memory was enshrined. Most women, even the greatest, had no memorials at allâFreydÃs EirÃksdóttir, for one, whose bad name had lasted a full thousand years.