The Pirate Queen (7 page)

Authors: Barbara Sjoholm

The insidious system of “surrender and regrant” played on the fragmentation of Ireland and was far less expensive than wholesale warfare. The chieftains were offered a bargain. All they had to do was submit to the authority of the English crown. They'd then be “regranted” their lands, with titles to boot. Many also received favors and financial advantages from the English crown. The catch was that in doing so they agreed to give up traditional Brehon law for English law, and to accept the right of sheriffs and justices to enforce it. Some chieftains surrendered quietly and others tried to work both sides. But for many, the notion of paying rents and taxes on estates that had been in their clans for centuries was intolerable, as was giving over many of their quasi-regal powers and privileges to Elizabeth's agents.

The conquest of Ireland proceeded erratically, but unstoppably, throughout the sixteenth century. Elizabeth sent provincial governors to offer terms to the chieftains, and began establishing bastions of the English legal system. There were many rebellions, of course, and outright battles, not all of which the Irish lost. But Elizabeth's deputies played a divide-and-conquer game, inserting themselves into the rivalries between and

among the clans. One chieftain after another became either an English peer or a corpse.

Lord Deputy Henry Sidney (the father of poet Sir Philip Sidney) paid his fourth visit to Galway in 1577, intent on “colonization by persuasion.” Along with many others, Grace appeared before him to voluntarily submit to Elizabeth. She impressed Sidney, as was her intention, with an account of her many ships and fighting men. Sidney later wrote:

There came to mee also a most famous femynyne sea capten called Grany Imallye, and offred her service unto me, wheresoever I woulde command her, with three gallyes and two hundred fightinge men, either in Ireland or Scottland, she brought with her her husband, for she was as well by sea as by land well more than Mrs Mate with him. . . . This was a notorious woman in all the costes of Ireland.

Grace had little intention of actually giving up power, and shortly after meeting Sidney, she launched a raid on the estates of the earl of Desmond, one of the Gaelic chieftains who had taken an English title in the south of the country. He captured her, however, and turned her over to the English in an attempt to curry favor with the new rulers. She spent months imprisoned at Limerick before being transferred to the dungeons of Dublin Castle. Lord Justice Drury, who dealt with her then, called her “a woman that hath impudently passed the part of womanhood and been a great spoiler and chief commander and director of thieves and murderers at sea to spoil this province. . . .” But he also described her as “famous for her stoutenes of courage and person, and for some sundry exploits done at sea.”

Grace spent eighteen months altogether in the dungeons of

Limerick and Dublin castles, cruel punishment for a woman who'd ranged far and wide across the seas. Soon after she was released, the castle at Rockfleet was attacked, and the next years required much cunning. She and Richard Bourke took titles in 1581, and though Richard died in 1583, “Lady Bourke” continued as the de facto head of the clan, supported by Bourke relatives and her own children, two of whom, Owen and Margaret, had also married Bourkes. She was then fifty-three, already long past the life expectancy for a woman in those times. Her most difficult years lay ahead.

In 1584 Sir Richard Bingham became governor of Connaught. Unlike Sir Henry Sidney, Bingham believed more in “colonization by the sword” than “colonization by persuasion.” Bingham came to take a hard line with the clan leaders who were resisting English power, by laying waste to their estates, putting them in prison, and isolating them from their followers. He pursued Grace O'Malley with single-minded zeal. To his way of thinking, she had no legal entitlement as a widow to the Bourke property, and absolutely no right to rule. Not only had she been attacking and plundering English ships for the last twenty years, but this “nurse to all rebellions,” as he termed her, was still fomenting mischief among the clans. Lady Bourke was no more subject to the queen than she had ever been.

Bingham set out to destroy her, and very nearly succeeded. Several of the Bourke clan, including Grace's stepsons, were executed by martial law, and her oldest son, Owen O'Flaherty, was murdered underhandedly, even though he had not joined his clan's rebellion against Bingham's government. Bingham also kidnapped her youngest son, Tibbot, and sent him to his brother, George Bingham, as a hostage, so that Tibbot could learn the English language and be tutored in the ways of the

English. At one point Bingham imprisoned Grace herself:

She was apprehended and tied with a rope, both she and her followers at that instant were spoiled of their said cattle and of all they ever had besides the same, and brought to Sir Richard who caused a new pair of gallows to be made for her where she thought to end her days.

Bingham could have killed her; instead, her daughter Margaret's husband, whom the English called the Devil's Hook, offered himself as hostage, and Grace was set free. She fled north with her ships and continued to foment mischief. Bingham killed the cattle on her estates and burned her crops. He found his way into the treacherous waters of Clew Bay, and impounded her fleet, thus destroying her livelihood.

The loss of her cattle and crops was misery, but the loss of her ships was intolerable. With cunning amplified by desperation, Grace, now sixty-three, composed a courteous and politically wily letter to Queen Elizabeth, dated 1593, thus opening a correspondence with the English state. Her petition didn't challenge Elizabeth's right to rule Ireland, but was, in effect, a sort of special pleading for herself and some of her relatives. Her aim was to protect herself from Bingham, to procure the release of her son Tibbot, captured and imprisoned by Bingham a second time, and to get back to her business at sea. After establishing contact with the court, Grace set off by sea, evading Bingham and making her way up the Thames.

In London, like multitudes of petitioners, she waited for an audience with the queen, and found herself a friend at court, Lord Burghley. This statesman and close advisor to the queen had been aware of Grace O'Malley for twenty years and was

intrigued enough to send her a sort of questionnaire, the “Eighteen Articles of Interrogatory to Be Answered by Grany Ne Maly.”

I try to picture this Irish chieftain and pirate queen sitting in Shakespeare's London giving detailed answers (in the third person, and doubtless through a scribe and/or interpreter) to such questions as “Who was her father and mother? Who was her first husband?” and deftly fielding the query “How she hath had maintenance and living since her last husband's death?” by answering humbly that after returning to Carraigahowley and fleeing Bingham, “she dwelleth in Connaught a farmers life very poor . . . utterly did she give over her former trade of maintenance by sea and land.” The questionnaire and her answers are a historian's dream come true, and I can only imagine Anne Chambers's thrill when she discovered the parchment pages in the Public Record Office in London, and began to decipher the difficult English script. For in Grace's answers, not only do we learn important facts about Grace O'Malley's life and her relations, but we can also see the construction she has put on them, her way of emphasizing her harmlessness and skating over her part in any rebellions against the English rulers.

The eventual meeting between Grace and Elizabeth at Greenwich Palace is the stuff of legend, the centerpiece of many a ballad and historical novel about the Pirate Queen. Although some chieftains of Ireland had previously gone to England to parley with the queen, most ended up in the Tower of London. Grace was one of the few to find the queen's favor and to sail back to Ireland with everything she sought: freedom for her son Tibbot, an end to Bingham's pursuit of her, and, most importantly, a return to what Grace euphemistically called “maintenance by sea and land,” that is, piracy.

Â

Before the English Queen she dauntless stood,

Â

And none her bearing there could scorn as rude;

Â

She seemed as one well used to powerâone that hath

Â

Dominion over men of savage mood,

Â

And dared the tempest in its midnight wrath,

Â

And thro' opposing billows cleft her fearless path.

Â

And courteous greeting Elizabeth then pays,

Â

And bids her welcome to her English land

Â

And humble hall. Each looked with curious gaze

Â

Upon the other's face, and felt they stand

Â

Before a spirit like their own.

Of course no one knows exactly what went on at their meeting. It's said they spoke in Latin, the only language they had in common, and that when Elizabeth offered to make Grace a countess, she refused, apparently feeling she had already attained the same status as the queen. There's also a story that Queen Elizabeth offered Grace a handkerchief when she sneezed. After blowing her nose heartily, Grace tossed the embroidered cloth into the open fireplace. The court was shocked to see this. “In England,” a courtier rebuked her, “We do not throw handkerchiefs in the fire.” “What do you do with them then?” asked Grace with interest. “We save them for another time.” “What! You save a dirty piece of cloth? The queen may do this, but not I.”

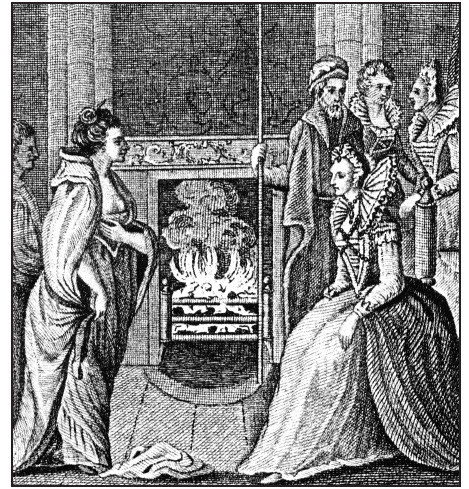

Amusing as this is, it's probably unlikely that Grace would have done anything to insult Elizabeth. Yet imagining an encounter between two such similar women, more or less the same age, who operated in a man's world, has fascinated many. The Granuaile Heritage Centre has an elaborate diorama of

their meeting at the Tudor courtâQueen Elizabeth with whitened face set off by a huge ruff and red wig and Grace, gray-haired and bent over, disguised in a shabby simple cloak, an elderly mother asking only for her beloved son's freedom.

This scene suggests that Elizabeth thought Bingham must have been dreaming, to believe such a worn old woman could be a threat to the crown, and in fact later Elizabeth wrote to Bingham ordering him “to have pity for the poor aged woman.”

Eventually, with Lord Burghley's influence, Elizabeth commanded Tibbot's release and recommended that Grace O'Malley and her son be able to live undisturbed the rest of their lives. I imagine Grace throwing off the shabby cloak as soon as her ship was out of the Thames, and raising her saber high as she set off for the wilder shores of Ireland again. Elizabeth had given Grace and her clan permission to fight the Spanish and French on behalf of the English crown. Grace, of course, interpreted this in her own way, as license to return to plundering ships off Ireland's coast.

Not long after, she was reported to have built three large galleys, each big enough to carry three hundred men. Sir Richard Bingham continued to make life miserable for her and her clan, however; two years after her first visit to Queen Elizabeth's court, she returned to England with a petition for Lord Burghley, complaining that Bingham made it impossible to claim her property and go about her business. Grace's persistence in claiming her rights was rewarded. In 1595 Bingham's own followers conspired against him, and he was forced to flee Ireland for England, where he found himself in prison.

Now there was little to hinder Grace from returning to the sea with her pirate galleys, and one of the last written references to her comes from an English captain who skirmished with one of her ships and got the better of the crew: “This galley comes out of Connaught,” he wrote of the encounter, “and belongs to Grany O'Malley.” At the time she was seventy-one.

The meeting of Grace O'Malley and Queen Elizabeth I

She died in Rockfleet Castle, it's said, in 1603, the same year as Queen Elizabeth. The old Ireland was gone; Grace's son Tibbot-ne-Long, as astute as his mother, saw which way the wind was blowing, and came out on the side of the English in the Battle of Kinsale, which put an end to serious Irish resistance. For his loyalty to the crown, Tibbot-ne-Long was

knighted Sir Tibbot, and amassed the greatest estate in Mayo. Charles I later made him Viscount Mayo and it's this line, of Bourkes and Brownes, that still owns Westport House, even though the clan of O'Malleys is legion. Grace disappeared from history, though not from memory. She was kept alive in family stories, and in legends told around Clew Bay for centuries.