The Places in Between (4 page)

Read The Places in Between Online

Authors: Rory Stewart

Yuzufi smiled. He was meant to be searching for the letters of introduction I had acquired with trouble in Kabul. I waited for him to say that he had found them. He didn't. Instead, he said, "I was thinking about you last night, Rory. You are like a medieval walking dervish."

He compared me to Attar, who lived in the twelfth century under the dynasty of Ghor. When Genghis Khan invaded, Attar was killed for making a joke, and Rumi, whom Attar had held as a baby, walked to Turkey to found the whirling dervishes.

"What you will see on your walk," he continued, "is that we are one country today just as we were in the twelfth century under the Ghorids, in Attar's day."

I smiled. Whereas the new governor was learning the jargon of a postmodern state, Yuzufi had an older view of an Afghanistan with a single national identity, natural frontiers, and ambassadors and a culture defined by medieval poetry. The Security Service saw my walk only as a journey to the edge of Ismail Khan's terrain. The Hazara area was as foreign to them as Iran. But for Yuzufi my walk was a journey across a united country. Perhaps this was why he was one of the only people who thought the walk possible.

"I," Yuzufi sighed, "would love to come with you, but I am like the birds that refused to join the sacred quest." Then he quoted some poetry that may have been Attar's description of the birds' excuses for staying at home:

The owl loves its nest in the ruins,

The Huma revels in making kings,

The falcon will not leave the King's hand,

And the wagtail pleads weakness.

2

Finally a soldier marched in and, holding his right hand to his chest, said, "

Salaam aleikum. Chetor hastid? Jan-e-shoma jur ast? Khub hastid? Sahat-e-shoma khub ast? Be khair hastid? Jur hastid? Khane kheirat ast? Zjnde bashi.

"

Which in Dari, the Afghan dialect of Persian, means, "Peace be with you. How are you? Is your soul healthy? Are you well? Are you well? Are you healthy? Are you fine? Is your household flourishing? Long life to you." Or: "Hello."

He was a small man in his mid-forties with bandy legs, a wispy chestnut brown beard, and pinched purple cheeks. In a webbing pouch he carried a military radio, his link to headquarters; a pen, suggesting he was literate; a packet of pills, showing he could afford antibiotics; and a roll of pink toilet paper, a more subtle status indicator.

Yuzufi did not stand up to greet him, but he moved three files on his heavy wooden desk and replied with his nine greetings. Against the far wall of the office, four Afghan villagers sat uncomfortably straight on plastic chairs, their rubber galoshes planted squarely on the linoleum. Beneath frayed

shalwar

pajama trousers, their narrow brown ankles were covered with white hairline cracks and scars. They had been waiting for hours to speak to Yuzufi.

"I am Seyyed Qasim," continued the soldier, emphasizing the title

Seyyed,

meaning descendant of the Prophet, "from the Department for Intelligence and Security."

"Indeed.

Seyyed

Qasim, I am His Excellency Yuzufi," Yuzufi, who was also a

seyyed,

replied. "This is His Excellency Rory, our only tourist, standing by, ready for you to walk with him."

My escort did not glance in my direction.

"

Salaam aleikum,

" I said.

"

Waleikum a-salaam,

" the small man replied. He turned back to Yuzufi. "Well, Your Excellency, we have a Land Cruiser outside."

"Please understand," I interrupted, "I am walking to Chaghcharan."

"To Chaghcharan? No." Seyyed Qasim stood straight and made firm statements, but he did not seem comfortable in this office. He kept looking around the room. His eyes were small and blue, his eyelids puffy.

"Not just to Chaghcharan," said Yuzufi, "to Kabul."

"He will be killed. What is this foreigner trying to do?"

"I am a professor of history," I said.

Qasim squinted at my shabby clothes and frowned.

The door swung open and a younger soldier marched in and saluted. He was about six feet tall—nearly seven inches taller than Qasim—and much broader than Qasim in the shoulders. Unusually for an Afghan who came from a rural area, he had shaved his beard, leaving a drooping mustache that made him look like a Mexican bandit. Visible in his webbing were five spare magazines, three grenades, a packet of cigarettes, and again a bundle of pink toilet paper. Qasim introduced him as Abdul Haq.

Yuzufi, who had been skimming two files, now looked up and spoke to them at length. Turning to me he added, "I have told these two that you have met His Excellency the Emir, Ismail Khan, and that he wished you luck on your journey. They are to do what you instruct and you will record their bad behavior. Your walk starts now." He stood up from behind his desk and gravely enfolded my hand. "Record me in your book. As the Persian poet says: 'Man's life is brief and transitory, Literature endures forever.'"

He smiled. "Good luck, Marco Polo."

FARE FORWARD

We walked down the corridor and pushed through the crowds still waiting to present petitions to the governor. When we reached the street, rather than turning west to the hotel, we turned east toward the desert and the mountains. The sun had come out, casting a harsh clear light over the sand-caked brick and sharpening the shadows of tired men pushing handcarts. As we walked, I adjusted the straps of my pack and wondered what I had forgotten to buy and would therefore have to do without for the next two months. I felt the familiar unevenness in the inner sole of my left boot, stretched my toes, and paced out. My companions were carrying only automatic rifles and sleeping bags, and had no food or warm clothing.

I felt a little ludicrous in my Afghan clothes, shrugging my shoulders under the weight of the pack. Qasim, the older man, was wearing neatly pressed camouflage trousers made for someone much larger. He had gathered the loose waist in pleats beneath his belt, but the thigh pockets reached his midcalf. Although he was the senior man, Qasim seemed much less comfortable than Abdul Haq. He kept his red, pockmarked face down, his eyes flickering nervously as though he were waiting for something to erupt from the pavement. Abdul Haq had an upright stance and looked very tall beside Qasim. He took two paces for every three of Qasim's.

Nobody on the street even glanced at us and neither Qasim nor Abdul Haq looked at me. They didn't speak English. I guessed that they had only an uncertain idea of the walk ahead, that they had not dealt with a foreigner before, and that they were relatively junior. Since their uniforms looked as though they had just been unpacked from an American consignment, I also assumed they were new to their jobs. But they handled their weapons comfortably. We walked side by side, or almost, for the street was crowded and Abdul Haq stopped a couple of times to adjust the circular magazine on his Kalashnikov. The sand on the rough asphalt became thicker and the crowds thinned.

I looked into the blank eyes of a crow sitting on a wall. Beneath it an antique shop's wares were displayed on a tray. Beside a nineteenth-century Gardener teapot and two Lee Enfields with splintering stocks were a tile from the Musalla Complex, a Gandharan head of a Buddha, and a mythical bird shaped in clay: objects from Babur's Herat and the civilizations of Bamiyan and Ghor baldly presented in the dust for trinket hunters. I doubted the seller cared any more for them than did the crow. We passed pastry shops and pharmacists and dust-caked fruit in boxes and the last gas station.

Finally, Abdul Haq looked at me with his dark eyes and asked, "You're not a journalist, are you?"

"No."

"A pity; otherwise you could write a story about us."

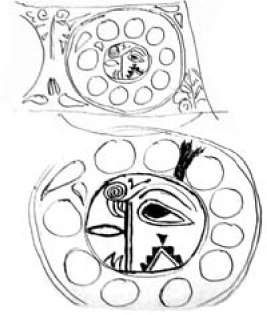

Fragment of an ancient vase from Ghor

At the edge of the city, we sat on a table in the street to eat lunch. We had a choice of eggs, bread, and yogurt but I had had enough eggs for the day. Qasim pulled his small legs up underneath him, carefully took my bowl of yogurt, stuck in his small finger, and licked it before handing the bowl to me. It seemed he was showing his concern for his guest by checking for poison. Poisoning was common in medieval courts. Babur once disemboweled a cook for it. Qasim's gesture, however, was merely a show of good manners. I thanked him and smiled. For the first time, he smiled back.

Opposite our food stall stood elaborate medieval mud towers, built to house pigeons because their droppings fertilized the vineyards. The Taliban had burned the vineyards and banned the keeping of birds. The ornate balconies of the towers were crumbling and pigeonless. In the past, the pigeons were kept for pleasure too. Like Hussein Mirza, the fifteenth-century ruler of Herat, Babur's father owned pigeons trained to somersault in the air. When his city was being invaded and he was on the verge of defeat, he went to his pigeon tower, which stood on a cliff. Babur writes that the land slipped, the cliff collapsed, and "the pigeons and my father took flight to the next world."

After lunch, we walked on. At the outskirts of town, we passed one of the traditional junctions for the Silk Road, where the caravan route turned north to China or south to India—the route taken by the hippies in the 1970s. We continued east. I was just beginning to feel that I had left Herat and started on my journey. Then a jeep clattered up and stopped beside us. It was David from the

Los Angeles Times,

who had run out of stories and wanted to know if he could interview me.

I liked David. He had allowed me to use his satellite phone to call my parents. This was a privilege, for there would be no phone in the next six weeks of walking. Now he asked me why I was walking across Afghanistan.

I told him Afghanistan was the missing section of my walk, the place in between the deserts and the Himalayas, between Persian, Hellenic, and Hindu culture, between Islam and Buddhism, between mystical and militant Islam. I wanted to see where these cultures merged into one another or touched the global world.

I talked about how I had been walking one afternoon in Scotland and thought:

Why don't I just keep going?

There was, I said, a magic in leaving a line of footprints stretching behind me across Asia.

He asked me whether I thought what I was doing was dangerous. I had never found a way to answer that question without sounding awkward, insincere, or ridiculous. "Surely you can understand," I said, "the stillness of that man, Qasim. The Prussian blue sky—this air. It feels like a gift. Everything," I said, warming to my theme, "suddenly makes sense. I feel I have been preparing for this all my life."

But he wrote none of this down. Instead, while Loomis, his photographer, shot pictures of me from a ditch, he apparently scribbled, "20—27 miles a day every day—living on bread—'the hunger belt.' Babur loses men and horses in the snow. One change of clothes. Thin with a wispy beard." When Loomis gave me a plastic-wrapped hand warmer, I tried to explain that the physical side didn't matter to me, that it was more a way of looking at Afghanistan and being by myself.

Loomis nodded. "Have you read

Into the Wild

. . . that book about the wealthy young American who headed off into the Alaskan wilderness to find himself and then died on his own in the snow? ... It's a great piece of journalism."

They returned to Herat and we continued. Abdul Haq pushed his baseball cap onto the back of his head, smoothed down his long Mexican mustache, shrugged to throw his American camouflage jacket back on his shoulders, and moved five yards in front of me, leaning so far forward that he was forced to walk quickly just to stay on his feet. A cloud of apricot sand billowed around his boots. It mingled with the gray smoke trailing from his cigarette, which he hid by his thigh in the traditional pose of a soldier smoking on duty. Beside me, Qasim took smaller, pedantic steps, bringing his heel down sharply on the edge of the road.

Our shadows lengthened on the gravel: Abdul Haq's the largest, Qasim's the smallest, mine with a hunchback formed by my pack. The desert grew around us and the three of us diminished in size. I kept thinking of David's article as a distorted obituary, and it took some time for my muscles to warm and to settle me into the familiar rhythm of another day's walk. When I caught up with him, Abdul Haq flashed a smile, stuck the barrel of his rifle into the sand, and performed a miniature pole vault, shouting "

Allah-u-Akbar

" (God is Great) as he landed. Qasim scowled at the younger man. I wondered how much control he had over his deputy.

I was used, apart from my weeks in the Maoist areas of western Nepal, to walking in relatively peaceful areas. Although I walked about forty kilometers every day, I met few people, and the scenery, at five kilometers an hour, changed very slowly. I was accustomed to concentrating on details: the great shisham trees in the Punjab, leopard tracks in the lowland jungle, the pale green

brahma

flowers of the Himalayas. I recorded all the objects in village guest rooms. I examined battery chicken farms and truck stops in Iran; in Nepal I watched men plowing with white oxen, flails striking the threshing floor and the clouds of chaff in the sun. I recorded people's experiences as manual laborers in Saudi Arabia and their conspiracy theories about America. I tried to uncover traces of ancient history along the Indian-Nepali border, following a line of battered stones—carved with cavalry and the sun god—that was, I thought, an ancient imperial Malla footpath.

3