The Pleasure of My Company (19 page)

Read The Pleasure of My Company Online

Authors: Steve Martin

Tonto.

That’s

who I felt like when I heard the footsteps coming along the second-floor

walkway. I thought to myself, “There are two of them, Kemosabe, and they’re

coming this way.” I heard Clarissa ‘5 voice, then a man’s. They spoke slowly,

each response to the other delivered in the same whispered tone. Her answers

were shy; his questions were confident and cool. They passed the window and I

saw him looking at her as she looked down, fumbling for her keys. The door

opened and he stood outside while she moved in, putting her purse down and

turning around to him. He spoke to her, and he stepped into the apartment. Her

hand touched the light switch and the hard overheads went out, sending my body

into rigor mortis. But I watched. They spoke again and he put his hand on her

arm, pulling her toward him. She responded. He moved his hand, sliding it up

under her hair. He drew her into him and rested his forehead on hers, and I

watched him close his eyes and breathe deeply to absorb her. His lips brushed

her cheek and I saw her surrender, her shoulders dropping, her arms hanging

without resistance. His hand went to her back and urged her, pressing her

against him. Her arm went up to his waist, then around his back, and he moved

his lips around to hers and kissed her, her arm tightening, locking on his

back, her other arm sliding up to his elbow. Her head fell back and he continued

kissing her, standing over her, then he stepped back and looked into her eyes,

saying nothing.

It is

hard to find that the person you love loves someone else. I knew that my tenure

with Clarissa and Teddy would have an end.

It was early June, and I

had continued my pattern with Teddy, and had continued to incrementally

withdraw my attachment to Clarissa. There were other nights, nights involving

quiet door closings and early morning slip-outs. These sounds made my detachment

easier, even though there was no official announcement of a pledge of love,

even though, as far as I knew, there was no introduction of the new man to

Teddy, which I felt was wise of Clarissa and protective toward her child.

On a

particularly disastrous afternoon I was in charge of Teddy and he and I engaged

in a battle of wits. My mind was coherent, rational, cogent. His was not. As

compelling as my arguments were, his nonverbal mind resisted. We had no

unifying language or belief. I wanted a counsellor to mediate, who would come

and interpret for us, find common ground, a tenet we could agree on, then lead

us into mutually agreed-on behaviour. All this angst was focused on a cloth

ring that fit over a cloth pole. He screamed, he wanted it, he didn’t want it,

he cursed—I’m sure it was cursing— and there was absolutely no avenue for calm.

But there were moments of transition. The moments of his transition from

finding one thing unpleasant to finding another unpleasant. And he would gaze

into my eyes, as if to read what I wanted from him so he could do the opposite.

But these transitions were also moments of stillness, and in stillness is when

my mind churns the fastest. I looked into the wells of his irises, into the

murky pools of the lenses that zeroed in and out.

I had

spent time with him; I had been the face, on occasion, that he woke up to. I

was fixed in him; my image was held in his consciousness, and I wondered if his

recollection of me had slipped beneath the watermark of his awareness and

entered into a dreamy primordial place. I wondered if he saw me as his father.

If he did, everything made sense. I was the safe one, the one he could rage

against. The one from whom he would learn the nature, the limitation, and the

context of the cloth ring on the cloth pole.

I

constructed a triangle in my head. At its base was Teddy’s identification of me

as hero, along its ascending sides ran my participation in Teddy’s life,

however brief that participation might prove to be. At the apex was the word “triumph,”

and its definition spewed out of the triangle like a Roman candle: If one day

Teddy, the boy and child, approached me with trust, if one morning he ran to my

bedroom to wake me, if one afternoon he was happy to see me and bore a belief

that I would not harm him, then I would have achieved victory over my past.

But my

thoughts did not mollify Teddy; he wanted action. It was now dusk and he

continued to orate in soprano screams. I decided a trip to the Rite Aid was in

order, and he softened his volume when I swept him up and indicated we were on

our way outside.

The sky

over the ocean was lit with incandescent streaks of maroon. The air hinted that

the evening would be warm, as nothing moved, not a leaf. Teddy, a strong

walker now, put his hand up for me to take, and I hunched over and walked at

old-man speed. We walked along the sidewalk and I occasionally would playfully

swing him over an impending crack. I approached the curb, where I normally

would have turned left and headed eight driveways down to where I could cross

the street. But I paused.

My hand

smothered Teddy’s. I looked at him and knew that after my cohabitation with

Clarissa was over, he might not remember me at all. Yet I knew I was

influencing him. Every smile or frown I sent his way was registering, every

raised voice or gentle praise was logged in his spongy mind. I wondered if what

I wanted to pass along to him was my convoluted route to the Rite Aid, born of

fear and nonsense, if what I wanted him to take from me was my immobility and

panic as I faced an eight-inch curb. Or would I do for him what Brian had done

for me? Would I lead him, as Brian had me, across the fearful place and would I

let him hold on to me as I had held on to Brian? Suddenly, turning left toward

my maze of driveways was as impossible as stepping off the curb. I could not

leave Teddy with a legacy of fear from an unremembered place. I pulled him

toward the curb so he would not be like me. Recalling the day I flew over it

with a running leap, I put out one foot into the street, so he would not be

like me. He effortlessly stepped off, swaying with stiff knees. I checked the

traffic and we started forth. I walked him across the street so that he would

not be like me. I led him up on the curb. I continued my beeline to the Rite

Aid, a route I had only imagined existed. Across streets, down sidewalks, in

crosswalks and out of them, all so Teddy would not be like me. I was the

Santa

Maria

and Teddy was the

Niña

and

Pinta.

I led, he followed. I

conquered each curb and blazed a new route south and achieved the Rite Aid in fifteen

minutes.

As I

entered the store, I did not feel any elation; in fact, it was as if my triumph

had never happened. I felt that this was the way things were supposed to be,

and I sensed that my curb fear had been an indulgence so that I might feel special.

I let Teddy’s hand go and he shifted into cruise. I followed him down the

aisle, sometimes urging him along, once stopping him from sweeping down an

entire display of bath soaps. I did not, however, prevent him cascading an

entire bottom row of men’s hair colouring onto the floor.

I sat

Teddy down and tried to group the dyes in their previous order. Men’s medium

brown, men’s dark brown, men’s ash blond. Men’s moustache brown gel. A woman’s

arm extended into the mess and picked one up. Her skin was exposed at the wrist

because her lab coat pulled back as she reached. She wore a small chrome watch

and a delicately filigreed silver bracelet, so light it made no noise as it

moved. As her arm reached into my vision, I heard her say, “Is he yours?”

I looked

up and saw Zandy, who was a full aisle’s length away from her pharmacy post,

and I wondered if she had intentionally walked toward us or was just passing

by.

“No, he

belongs to a friend.”

“What’s

his name?” she said.

“Teddy.”

“Hello,

little man,” she said. Then she turned to me, “I fill your prescriptions here

sometimes, so I know all your maladies. My name’s Zandy.”

I knew

her name and she knew mine, but I told her again, including my middle name, and

she cocked her head an inch to the sky. We had now gotten all the hair dye back

on the shelf, and Zandy stood while I crouched on the ground wrangling Teddy. Zandy

wore panty hose that were translucent with a wash of white, and she had on

running shoes that I assumed were to cushion her feet against the concrete

floors of the Rite Aid. While I took in her feet and legs, her voice fell on me

from above:

“Would

you like to get a pizza?”

Teddy

and I, led by Zandy, walked around the corner to Café Delores and ordered a

triple something with a thin crust. I looked at Zandy and thought that she

occupied her own space rather nicely. I thought of the status of my love life,

which was as flaky as the coming pizza. I knew it was time. I decided to summon

the full power of my charisma and unleash it on this pharmacist. But nothing

came. It seemed there was no need because Zandy was in full charge of herself

and didn’t need anything extra to determine what she thought about me. I said, “How

long have you worked at the pharmacy?” But instead of answering, she smiled,

then laughed and put her hand on mine, and said, “Oh, you don’t have to make

conversation. I already like you.

Zandy Alice Allen proved

to be the love of my life. I asked her once why she started talking to me that

day and she said, “It was the way you were with the boy.” After seeing her for

several weeks, I recalled Clarissa’s front-door kiss. I emulated her seducer

and one night at Zandy’s doorstep, pressed her against me. Her head fell back

and I kissed her. Her arms dropped to her side, then after a moment of

helplessness, she raised her hands and held my arms. She drew in a breath while

my lips were on hers, and I think she whispered the word “love,” but it was

obscured by my mouth on hers.

Once we

were at lunch and she asked how old I was and I told her the truth: thirty-one.

Months went by and she got to the heart of me. With a cheery delicacy she

divided my obsessions into three categories: acceptable, unacceptable, and

hilarious. The unacceptable ones were those that inhibited life, like the

curbs. But Teddy had already successfully curtailed that one; each time I

approached a corner, I envisioned myself as a leader and in time the impulse

vanished. The other intolerable ones she simply vetoed, and I was able to adjourn

them, or convert them into a mistrust of icebergs. The tolerable ones included

silent counting and alphabetizing, though when Angela arrived she left me

little time to indulge myself. We compromised on the lights, but eventually Zandy’s

humour—which included suddenly flicking lamps on and off and then dashing out

of the room—made the obsession too unnerving to indulge in.

It took six months and a

wellspring of perseverance for me to stop the government checks from coming in.

I was able to go back to work for Hewlett-Packard and I moved up the ladder

when I created a cipher so human that no computer could crack it. Zandy and I

lived at the Rose Crest after Clarissa left, though she and Teddy stayed in our

lives until one day they just weren’t anymore. I knew that what happened

between Teddy and me would one day be revealed to him. One night Zandy and I

were in bed and she leaned over to me and whispered that she was pregnant, and

I pulled her into me and we entwined ourselves and made slow and silent love

without breaking our gaze to one another.

Angela

was born on April

5,

2003, which pleased me because her twenty-first

birthday would fall on a Friday, which meant she would be able to sleep late

the next day after what would undoubtedly be a late night of partying.

When

Angela was one year old, Zandy took her out to a small birthday fete for little

ladies only and I was left alone at the Rose Crest. From the window I could see

my old apartment and see my old lamp just through the curtains. This was the

lamp I had once dressed in my shirt and used as a stand-in to determine whether

Elizabeth could have seen me look at her, and now at the Rose Crest I felt far,

far away from that moment. I indulged myself in one old pastime. As I looked

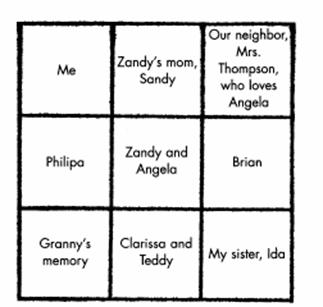

across the street, I built in my head my final magic square:

Other names came, but the

square overflowed and the confusion pleased me. I shifted away from the

window, turning my back on the apartment across the street. I moved to the

living room and sat, silently thanking those who had brought me here and those

who had affected me, both above and below consciousness. I thought of the names

in and around the magic square. I thought of their astounding number, both in

the present and past, of Zandy and Angela, of Brian, of Granny, even of my

father, whose disavowal of me led to this place, and I understood that as much

as I had resisted the outside, as much as I had constricted my life, as much as

I had closed and narrowed the channels into me, there were still many takers

for the quiet heart.